The “religion of pity” to which one would like to convert us—oh, we know the hysterical little males and females well enough who today need precisely this religion as a veil and make-up. We are no humanitarians; we should never dare to permit ourselves to speak of our “love of humanity”; our kind is not actor enough for that. Or not Saint-Simonist enough, not French enough. One really has to be afflicted with a Gallic excess of erotic irritability and enamored impatience to approach in all honesty the whole of humanity with one’s lust!

-Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science [snippet from §377]

The footnote for ‘Saint-Simonist’ only tells us that it refers to a utopian socialist by the name of Henri de Saint-Simon. But his use of the adjective to describe a ridiculously over-effusive sensibility is a little bit ironic, especially since Saint-Simon was betrayed by his business partner, had a failed marriage, went through rough struggles with poverty and ill health, and unsuccessfully tried to kill himself by shooting himself in the head. His suicidal despair resulted in part from the fact that most people didn’t really care about his ideas, which were essentially the ones that Nietzsche derides earlier in the section quoted above: progress, equal rights, and a free society.

But this sort of despair might be the result of an over-reach in terms of Saint-Simon’s ideal technocratic world. In Phaedo, Socrates points out the dangers of having visions of impossible worlds where everything is sunny, as it’ll eventually butt up against reality.

This could lead to some form of misanthropy or another, making one ‘dislike everybody and suppose that there is no sincerity to be found anywhere, that there is nothing stable or dependable either in facts or in arguments, and that everything fluctuates, and never stays at any point for any time‘.

Socrates might have had in mind Anaxagoras, a philosopher described by Harry Berger as ‘flying too high, bound to melt his wings and, wherever he dropped, was bound to find himself among ordinary folk who struck him as disorderly, unappreciative, and self interested, to be entrusted with nothing except a clog and a muzzle.’

I can’t help but see Nietzsche in this image, too. In the same section, he specifically talks about living apart from society to prevent ‘the silent rage to which we know we should be condemned as eyewitnesses of politics that are desolating the German spirit by making it vain‘. Indeed, there’s not much love for humanity that can blossom from such a high point, although Nietzsche himself pointed out in Ecce Homo that making up an ideal world scrubs the value from actual reality.

Like Nietzsche, Saint-Simon’s reputation took off a lot more after he died. There are also some similarities in thought: they both felt that splitting up the spirit and the flesh poisoned civilization, and that the current world we live in is the only one that matters. Saint-Simon’s disciple, Barthélemy-Prosper Enfantin, started a commune in the 1830s just as Nietzsche, Salomé, as Rée once planned to do. It didn’t go so well for Enfantin though, as he got himself thrown in prison for ‘offending public morality’, which Nietzsche was keen to do as a notorious immoralist. Also, Enfantin’s vision of a meritocratic society also has a little bit of an Übermensch flavour to it.

Saint-Simon didn’t care for what he called the idling class, and wanted to privilege industry, science and productivity above hereditary and military hierarchy, going so far as to give up his aristocratic title after seeing the relative lack of social privilege in the United States. I wonder if he would have seen Nietzsche as part of the idling class which he looked down on, since Nietzsche prized otium, although I don’t think Nietzsche’s books were the product of someone who loves lazing in the sun.

This ambiguity is expressed in Human, All Too Human §284, where he says that ‘leisure and idleness are a noble thing‘, but later asks: “You don’t think that by leisure and idling I’m talking about you, do you, you lazybones?“. A neat piece of trivia worth mentioning here is that the Greek word adoleschia can either mean subtle thought or idle chatter.

Saint-Simon’s vision of a future based on industry and science is pretty compelling and has kinda come true: I can grab a book from a catalogue of millions in a matter of seconds, and add it to a vast library which rivals that of any aristocrat. Would I be going too far to suggest that Saint-Simon’s technocratic vision of the future is similar to Nietzsche’s image of man as tied to a rope between beast and overman?

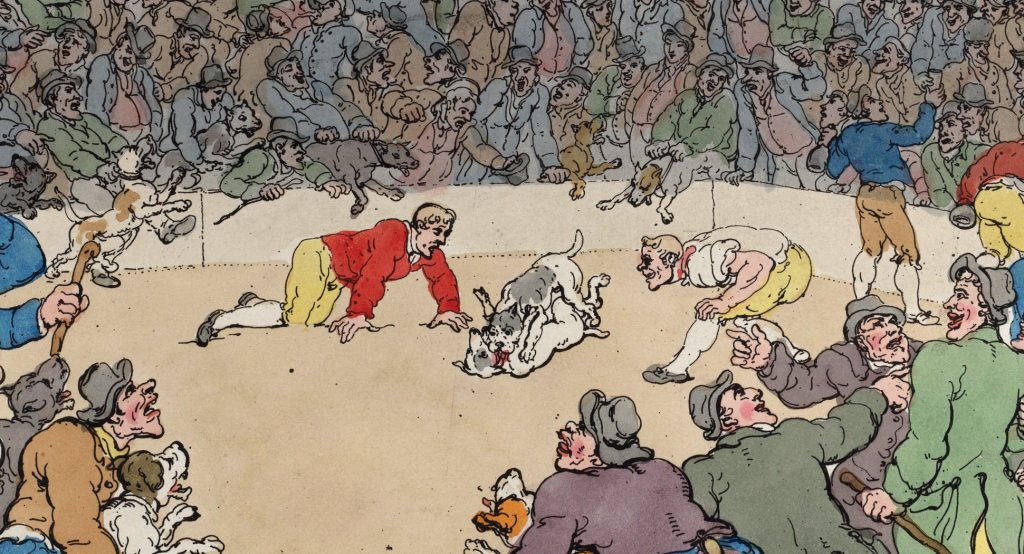

The values of progress, equality of rights and a free society seem immediately palatable to most people, but that’s in part because they’re so immediately recognizable as pro-social belief. It’s about wrapping your arms around the whole world, wanting to include everybody. There are some very dark aspects to progress, specifically scientific progress, which often depends on immense suffering inflicted on helpless creatures. As Schopenhauer put it, ‘every little medicine-man thinks he has the right to torment animals in the cruellest fashion in his torture chamber‘. Or even more bluntly: Men are the devils of the earth, and the animals are its its tormented souls. But beyond that, we should at least be honest with ourselves, we should not be actors, and assess the fact that for most people, most of the time, humanity is a deeply troubling, frightening and even disgusting spectacle.

Begone, Humans!

Although the traditional Greek mythological story has it that the Trojan War was caused by the abduction of Helen by Paris, we find a less romantic cause in a fragment of the Cypria, a lost part of the Greek epic cycle:

There was a time when the countless tribes of men, though wide-dispersed, oppressed the surface of the deep-bosomed earth, and Zeus saw it and had pity, and in his wise heart resolved to relieve the all-nurturing earth of men by causing the great struggle of the Ilian war, that the load of death might empty the world. And so the heroes were slain in Troy, and the plan of Zeus came to pass.

Since the Cypria would have been the fruit of a long oral tradition, we can only imagine that the disgust with people ruining the Earth would have been formulated before Cypria was written in the 7th century BC, at a time when Greece already had about two million people. We can find the same sentiment a long time before that in the Epic of Gilgamesh (~2100-1200 BC), where city populations would have numbered in the tens of thousands.

In Gilgamesh, we learn of a god named Enlil who is fed up with the sheer number of noisy human beings, and decides to flood the world so he can finally get a good night’s rest. One of the other gods named Ea warns a man named Utnapishtim, who in turn decides to build a huge ship to fill it up with people he loved or found useful, along with animals and grains. Enlil flips out once he hears of this, but Enlil’s son Ninurta calms him down by explaining that overpopulation can be curtailed by famines and dangerous animals. The Epic of Gilgamesh is a variation of an even older story which survives only in fragments, but the cause of the flood in these earlier documents is unknown, although I suspect it might be similar considering how often the theme pops up in other cultures around the world.

However, in some cases the tone is gentler. There’s a Navajo story where Coyote, who plays a big part in North American Indian mythology, is said to have proclaimed:

If we all live and continue to increase as we did in the past, the earth will be too small to hold us, and there will be no room for the cornfields. It is better that each of should live but a limited time on this earth, then leave and make room for the children.

A mythological story from the Bhuiya people of India tells of a beginning where people were immortal, which started to become a problem. The guy in charge, Mahaprabhu, began to wonder “where will there be room for all these people?‘

Among the indigenous Russian cultures like the Vogul it’s said that after marriage was introduced to the planet, people began to procreate to the point where food was desperately scarce and the world was plunged into poverty. As a solution, the sky god Numi-Tarem sent down Xul’ater, the Demon of Disease and Death, who dutifully spread sickness on the planet so as to clear things up a bit.

This sentiment is so ubiquitous that it has naturally found expression in modern Western culture, my favourite of which is in Bill Burr’s stand-up:

Nobody has the balls to come out and just say “Look, 85% of you have to go.” That’s it! I have been bitching about the population problem for three specials in a row. Waiting for some politician to have the balls to bring it up but they won’t do it. We live in a democracy, right? Can’t be honest in a democracy, you need the votes. You can’t run with that as your platform. Coming out there: “And if elected I would implement a program to immediately eliminate at least 85% of you. This planet cannot sustain the sheer numbers—let me finish!

It’s an unseemly idea that I suspect is held privately and not-so-privately by a lot of people, and one of the reasons Nietzsche was so frustrated with the saccharine mask of the ‘love of humanity’. Not everybody can gracefully express the idea, though. One day when I was waiting in line, I struck up a conversation with the man in front of me, a fella named Jacob, and somehow the topic of overpopulation came up. He made a striking remark about how there’s too many people on the planet, phrased in such a way that I immediately recognized it as being plagiarized from Bill Burr. I asked him if he was familiar with Burr and he predictably expressed a great enthusiasm for Bill’s comedy.

In contrast to Burr, however, Jacob’s contempt for the abundance of people had none of the self-deprecating jokes that tend to smooth out the rough edges in Billy boy’s act, nor Nietzsche’s ability to inhabit a multiplicity of mutually exclusive perspectives. I attributed this to Jacob’s day job, which involved working with sheet metal; it sounded physically grueling and he had the physical cuts to prove it, along with the spiritual ruts that allow for hatred to seep in. We were in line to buy weed, and he explained that he used the drug to obliterate his consciousness after coming home from work, dissolving my romantic image of fellow weed smokers as people who use it as a tool for spiritual and creative exploration.

I don’t think it’s rare to meet a man who suffers from a painful job and uses chemicals to repeatedly anaesthetize his soul as his hatred for humanity blooms. But the Mahabharata might offer some insight. In it, we find the overcrowded Earth complaining to the god Brahma about all the goddamned people. Brahma can’t figure out how to get rid of this nuisance effectively, and at one point gets so enraged with humans that he decides to wipe them all out. Shiva decides to step in to save humanity, and a compromise is made to send the goddess Death to Earth. However, Death finds this an awful job and begs to be fired, so Brahma gives her all sorts of assistants like Disease, Hatred, Greed, Violence, Jealousy, Envy and so on, figuring that with all these awful things, people will welcome Death as a great relief.

I’m tempted to speculate that the misery of life, especially as experienced in manual labour, can cultivate a strong hatred that makes the love of death blossom. Take, for example, this record from temple officials from Uruk:

On the 22nd of the month of Ayyaru of the first year of Cambyses, king of Babylon, king of all the lands, Misatu, a female serf of Istar of Uruk, took a lump of clay in our presence and beat a dog with it. We asked her: ‘Why are you beating the dog?’, and she replied ‘I would like to die together with it.’ The dog she beat died of the beating.

This comes from the prosperous Neo-Babylonian period in the 6th century BC, which had tremendous economic growth at the cost of treating a large class of people as expendable economic instruments. There was plenty to go around but not everybody was getting some, and many lived lives of painful drudgery with rage and hatred in their hearts. The reason that temple officials were interested in this incident was because such a death wish was subversive to productivity, and any kind of self-injury was ultimately going to harm the bottom line.

Demographers at conservative think tanks like the American Enterprise Institute suggest that overpopulation isn’t the issue, but rather, the problem is poverty. The scientific journal Nature ran an article on myths and cited overpopulation as a commonly misunderstood issue, explaining that there’s more than enough resources for everybody, but there’s a criminal negligence when it comes to the distribution of goods. I think that this is actually much worse news than overpopulation, since reducing the number of people on the planet is a simple intervention compared to altering deeply ingrained behaviors like greed and domination.

So Doggone Powerful

One of the ways I think Nietzsche is so helpful here is that he advocates for maximum flexibility of perspective. In the same section I quoted from in the beginning, he says:

[…] we are delighted with all who love, as we do, danger, war, and adventures, who refuse to compromise, to be captured, reconciled, and castrated; we count ourselves among conquerors; we think about the necessity for new orders, also for a new slavery-for every strengthening and enhancement of the human type also involves a new kind of enslavement. Is it not clear that with all this we are bound to feel ill at ease in an age that likes to claim the distinction of being the most humane, the mildest, and the most righteous age that the sun has ever seen?

When I read about being captured, reconciled and castrated, I think of dogs; I find it quite a nightmare to think that human beings have physically bred out the ability to resist, to be strong and independent. They smile at their chain and their captors. Like anybody else I appreciate and enjoy cute dog videos—they were specifically created to fire off the neurons that swoon at their adorable little faces.

Yet as an inveterate walker, I’ve had the displeasure of watching the abuse and neglect of dogs on a regular basis. I see dogs screamed at, hit, smacked, choked, dragged, yanked, and starved, although I’m not sure if I have any claim to moral superiority, since I would find relief in seeing a dog maul its owner in retaliation for abuse, as Schopenhauer did:

I think with satisfaction of a case, reported some years ago in The Times, where Lord X kept a large dog on a chain. One day as he was walking through the yard, he took it into his head to go and pat the dog, whereupon the animal tore his arm open from top to bottom, and quite right, too! What he meant by this was: ‘You are not my master, but my devil who makes a hell of my brief existence!’ May this happen to all who chain up dogs.

– Arthur Schopenhauer, On the Suffering of the World

I love to see Schopenhauer’s own claws and lust for life and freedom! How much more striking and awesome is an animal that is its own master, that has the ability to strike? The ability to incorporate the delight of danger, war and adventure means that a whole new vista of appreciation becomes open to us. As Nietzsche puts it in section 337:

Anyone who manages to experience the history of humanity as a whole as his own history will feel in an enormously generalized way all the grief of an invalid who thinks of health, of an old man who thinks of the dreams of his youth, of a lover deprived of his beloved, of the martyr whose ideal is perishing, of the hero on the evening after a battle that has decided nothing but brought him wounds and the loss of his friend. But if one endured, if one could endure this immense sum of grief of all kinds while yet being the hero who, as the second day of battle breaks, welcomes the dawn and his fortune, being a person whose horizon encompasses thousands of years past and future, being the heir of all the nobility of all past spirit—an heir with a sense of obligation, the most aristocratic of old nobles and at the same time the first of a new nobility—the like of which no age has yet seen or dreamed of; if one could burden one’s soul with all of this— the oldest, the newest, losses, hopes, conquests, and the victories of humanity; if one could finally contain all this in one soul and crowd it into a single feeling—this would surely have to result in a happiness that humanity has not known so far: the happiness of a god full of power and love, full of tears and laughter, a happiness that, like the sun in the evening, continually bestows its inexhaustible riches, pouring them into the sea, feeling richest, as the sun does, only when even the poorest fisherman is still rowing with golden oars! This godlike feeling would then be called—humaneness.