Every time I visit my maternal grandmother, Nina, she tells me that she just wants two things; to see me healthy, and to dance at my wedding. My paternal grandmother, Felicia, tells me that there’s sadness in her soul because I’m still a bachelor, and prays to God that this’ll change. Since I suspect that their perspective on marriage is based mostly on personal prejudice, I’m tempted to dismiss these wishes to pair up, but it’s not like I’ve looked into it much myself. To some degree, there must be something to be said for it, and I’ve noticed that I spontaneously associate wedding rings on people’s fingers with respectability, maturity, and sanity. The ring is presumably a clue that its wearer is more tolerable, like the metallurgic equivalent of a five-star Amazon review. This isn’t only a mental quirk on my part, since some sociologists writing about the rising case of involuntary bachelors in China, describe how involuntary male celibacy is ‘regarded solemnly as a symptom of the failure in the man’s life course’. I’m not alone in being alone either, since in 2016, for the first time in recorded Canadian history, single-person households were the most common kind. Should we be worried?

A few years ago, my girlfriend at the time invited me to a wedding ceremony, and being smitten with her I couldn’t refuse. The bride & groom were in their early twenties and I was pushing thirty, so it seemed slightly unhinged for them to make such a huge commitment before their frontal cortices are fully myelinated. Of course, Felicia and Nina made their decisions even earlier, 18 & 19, respectively. This is common; in 15th century Florence, for example, the deadline for a woman to get married was 19, and they’d be pushing past the limit if they were over 21, while 97% of women married by age 25. I had some reservations about the new couple’s wisdom, sure, but I made an effort to immerse myself in the experience and tone down my party-pooper vibe. Despite my hatred of boxing, I even managed to have a great conversation about the sport with the beefy guy sitting next to me, thanks to listening to a trillion hours of Rogan’s podcast.

The highlight of the ceremony was when they recited the opening of 1 Corinthians 13:

Though I speak in the tongues of men and of angels, but have not love, I am a sounding brass or a clanging cymbal. And though I have the gift of prophecy and understand all mysteries and all knowledge, and though I have all faith so as to remove mountains, but have not love, I am nothing. If I give all I possess to the poor and give over my body to hardship that I may boast, but do not have love, I gain nothing.

Love is patient, love is kind. It does not envy, it does not boast, it is not proud. It does not dishonor others, it is not self-seeking, it is not easily angered, it keeps no record of wrongs. Love does not delight in evil but rejoices with the truth. It always protects, always trusts, always hopes, always perseveres. Love never fails. But where there are prophecies, they will cease; where there are tongues, they will be stilled; where there is knowledge, it will pass away.

This gripped my body with frissons of delight, briefly cutting through the noise of my agitated mind. Taken the wrong way, it can be crushing to suggest that the actual worth of all knowledge and behaviour is predicated on something invisible and immaterial. But at the same time, it’s also obvious that without the right quality of consciousness, thoughts and actions are only husks of their true potential.

Of course, Paul didn’t use the English word love, rather the Greek agape, a spiritual kind of love as opposed to eros, which is related to the love of beauty and tends towards sexual attraction, hence the word erotic. Martin Luther King defined agape as ‘an overflowing love which seeks nothing in return‘, built out of ‘an understanding, creative, redemptive goodwill towards all men‘. Agape comes from agapao, which means ‘to prefer something‘, and matches the contemporary understanding of love. After all, in order to say you’ve fallen in love is to say you’ve developed an intense preference for someone specific.

The sense of boundless love that Paul associates with agape, however, makes it into a seemingly paradoxical notion of an unselective preferentiality. But that’s not to say it’s an incoherent idea. Buddhist practitioners might recognize this as metta, or loving-kindness meditation, which ultimately seeks to cultivate a sense of well-wishing for all sentient creatures. I can personally vouch for this frame of mind being a real possibility; one such meditative event was what I call my Gaia moment, where my sense of love for everyone felt so vast and spacious that I wanted to hold, cradle and nourish all living things. Even at the time I laughed at how strange this was, yet it still felt so right and peaceful.

Paul’s intention to separate agape from eros is hinted at in the opening to chapter seven, where he wrote that men and women should ideally stay away from each other:

As for the questions raised in your letter; a man does well to abstain from all commerce with women. But, to avoid the danger of fornication, let every man keep his own wife, and every woman her own husband. Let every man give his wife what is her due, and every woman do the same by her husband; he, not she, claims the right over her body, as she, not he, claims the right over his.

Do not starve one another, unless perhaps you do so for a time, by mutual consent, to have more freedom for prayer; come together again, or Satan will tempt you, weak as you are. I say this by way of concession; I am not imposing a rule on you. I wish you were all in the same state as myself; but each of us has his own endowment from God, one to live in this way, another in that. To the unmarried, and to the widows, I would say that they will do well to remain in the same state as myself, but if they have not the gift of continence, let them marry; better to marry than to feel the heat of passion.

Paul knew that agape is a distant dream for most people, so he immediately conceded the fact that the more common erotic love needs formal expression. From his perspective, marriage is a way to fix both porneia (πορνεία, meaning fornication, pronounced por-nee-ya) and pyrousthai (πυροῦσθαι, burning/passion, pronounced pee-ros-tay).

Porneia is a tricky word, since different cultures used it differently. The Greek use of the word was a more generic one that described sexual intercourse in general, like sex, and porne meant ‘sex man’ or ‘sex woman’. But Jewish culture used porneia as a catchall for anything they considered yucky Gentile behaviour, such as masturbation, homosexuality, extramarital sex, a woman on top, pegging, and oral sex. Also, the word must be partly understood against the related term μοιχεία, moicheía, or adultery (pronounced me-hee-ya). Women were technically regulated property of men in order to maintain so-called legitimacy, and divided into categories of ‘respectable’ and ‘non-respectable’. To have sex with a ‘respectable’ woman, regardless of her consent or marital status, meant to violate another man’s property. As a result, there was a big demand for ‘non-respectable’ women, and in fact, the ancient slave trade started as a way to add ‘non-respectable’ women into the marketplace. This grisly commodification of human life was seen as a solution for the the social chaos that erupted from moicheía or sexual competition, and it was common practice for men to avail themselves at a porneon or brothel. The Old Testament doesn’t really condemn men visiting female prostitutes, although it became a big issue in Second Temple Judaism.

In Greek culture, it usually wasn’t a big deal to have sex with other people, although Paul gives us clues about times when even their tolerance was stretched thin, like a man sleeping with his stepmom. But given the fact that women were sex slaves, sometimes captured as prisoners of war, the Corinthian porneon was the grimmest brothel you could imagine, and doubled as a clandestine cemetery for all the unwanted babies that they produced. Since this is a pretty good approximation of a living hell, it’s little wonder that Paul wanted the Christian community to avoid patronizing it. Porneia as Paul uses it is the shadow of sexuality that exploits, consumes and destroys. More broadly, Paul is concerned about pollution, and points out in the sixth verse of his letter to the Corinthians that men are effectively uniting their body with a harlot, which is a form of pollution of the body, and he was very concerned with cleanliness. Incidentally, it’s worth pointing out that there’s research suggesting that sexually transmitted diseases played an important role in the development of large cities as it served a way to control the promiscuous spread of pathogens. Devastating supers-preaders of AIDS, for example, had such a wide variety of sexual partners that it numbered in the hundreds.

When it comes to pyrousthai, it was a common belief in antiquity that sexual desire would physically inflame the body, and if it wasn’t periodically extinguished, it could destroy the victim. This is still a popular idea in contemporary culture, one of my favourites being Louis C.K. joking about how ‘cities should put a red tag on dicks with an unacceptable PSI level‘, summarizing male orgasm as ‘something that we need to do so we won’t murder people‘. In another bit, he accuses his wife of assassinating his sexual identity, and demoting sex to a perfunctory role. Clearly, he yearned for the return of his youthful pyrousthai. Unfortunately for him, that meant a wild PSI spike, as revelations of his sexual misconduct wound up destroying his reputation and career.

Addicted 2 U

While Paul made no secret of his personal opinion that celibacy is superior, he also emphasized that all of his instruction is meant to serve the interest of the listener, rather than the goal of keeping people on a tight leash. His guiding principle was the Holy Spirit—love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness— so he appreciated the fact that optimal interpersonal arrangements differ from person to person. This is more open-minded than some contemporary ideas about relationships, which is summarized by Amir Levine & Rachel Heller in their book Attached:

The ideal relationship is one between two self-sufficient people who unite in a mature, respectful way while maintaining clear boundaries. If you develop a strong dependency on your partner, you are deficient in some way and are advised to work on yourself to become more “differentiated” and develop a “greater sense of self.” The worst possible scenario is that you will end up needing your partner, which is equated with “addiction” to him or her, and addiction, we all know, is a dangerous prospect.

Amir Levine & Rachel Heller, Attached

While this seems pretty reasonable and is a useful perspective for some people, what the authors point out is that biologically speaking, dependence on partners is more like a fact rather than a choice. One tributary of the modern concept of self-sufficiency is that of nascent behaviorism from the early 20th century. During those simpler times, psychologists figured that children should be treated like little adults since society isn’t a friendly place. They shouldn’t be given too much attention, their cries should be ignored, and they weren’t to be touched while in hospital. If they acted up too much, they would be placed in foster care. As you might expect, this dramatically damaged the emotional well-being of the kids, as it turns out that the opposite is true. If only we could have anticipated that it’s a bad idea to emotionally neglect extremely sensitive, helpless and bewildered young creatures. Live and learn!

It wasn’t until John Bowlby came along that things started to change for the better. Bowlby was a casualty of this rough style of upbringing, as his parents were essentially strangers to him, the nannies he loved would leave unexpectedly, and he was sent to boarding school at an early age. As a way of making sense of his own suffering, he wound up studying psychology and working with juvenile delinquents. Corroborating his own struggle, he found that the most important factor in their pathology was the caregiving environment in early life.

Looking to ethology for inspiration to build an explanatory theory, Bowlby noticed there was a great similarity between human beings and other mammals when it comes to the behaviour of babies separated from their parents. The strategies they use (e.g., crying, clinging and searching) are ancient survival mechanisms, because the offspring that decides ‘screw you, I don’t need anybody!’ is probably going to starve and die. And given the fact that humans are helpless for a much longer time than any other animal, the built-in attachment behavioral system is vigilantly looking for an attachment figure that can provide support, protection and care. Determining whether or not this figure is available has important consequences in the development of a child’s personality, since the more the child feels an attachment figure is present, the more it can be sociable, confident, playful, and curious.

In other words, having support, and knowing there’s someone you can count on, is actually necessary for the brain to feel safe enough to become independent, a phenomenon dubbed the dependency paradox. You might see where this is going; this doesn’t quite disappear in childhood. But first, let’s explore this a little bit further. Mary Ainsworth, along with Mary Blehar, Everett Waters, and Sally Wall, took Bowlby’s ideas and developed a brilliant lil experiment to establish an empirical taxonomy of attachment styles in her ‘Strange Situation‘ test, which has been run thousands of times.

It goes like this: a 12-month-old child accompanied by its parent is brought into a room with a young, friendly researcher, and a bunch of fun toys to play with. After sitting in the lap of the parent to feel safe, the child closely inspects each toy with gleeful curiosity and plays to their heart’s content. As this is happening, the parent is taken into another room for three minutes, and of course, the kid becomes awfully distraught and no longer cares about the toys. They cry and bang on the door that mom or dad’s walked out of, even turning violent and hurling toys at the kind assistant who’s still in the room. After the parent returns, they take time to console the child, and then the kid’s back to toy heaven. In precise terms, the attachment provides a secure base from which children engage their exploratory drive.

This secure attachment style happens in about half of all cases. But there are other kids with an anxious-resistant attachment style, who make up about a quarter of the participants, and they’re difficult to console as they desperately crave reassurance, but also want to punish the parent. Then there’s the avoidant children, who suppress their signs of distress when the parent leaves, and actively ignore the parent when they return, even though their physiological response goes just as haywire as the other children. There’s a final category, the disorganized attachment style, characterized by inconsolable self-destructive behaviour like hitting the head against a wall. These tragic cases are as a result of things like severe trauma, neglect and abuse.

While each child may have a different attachment style depending on the parent, and mothers typically have a closer bond with their children than fathers do, cultural norms play into this as well. Ruth Feldman, Professor of Psychology and Neuroscience at Bar-Ilan University, has studied straight mothers who were primary caregivers, straight fathers who were secondary caregivers, and gay fathers who were primary caregivers. Mothers showed five times higher activation of emotional processing than straight fathers, whereas straight fathers had four times the activation of mentalization compared to the mothers. However, the gay fathers had high activity in both the emotional center and the mentalization center. Feldman doesn’t suggest that gay fathers are superior, but rather stressed the fact of neuroplasticity. She points out that for most of history, it was common for healthy, young women to die during childbirth, meaning that neighbors and relatives had to take care of children. The biological patterns of being a caregiver are flexible and don’t depend on gender, since it’s critical for the survival of infants. Indeed, Feldman also explains that straight fathers can also have their brain chemistry change if they become the primary caregiver.

Crooked Timber

Numerous studies show that once we become attached to someone, the two of us form one physiological unit. Our partner regulates our blood pressure, our heart rate, our breathing, and the levels of hormones in our blood. We are no longer separate entities.

Amir Levine & Rachel Heller, Attached

The most amazing example of physiological blending in relationships is outlined in a case study by Seanger and his team in the 1970s, where a sickly boy was taken to the hospital. Although he had adequate food intake, his growth was stunted and he had an alarming absence of growth hormones in his bloodstream. However, luck had it that he was assigned a nurse who gave him lots of TLC, and after a hundred days his growth more than doubled, with growth hormones tripling. Once the nurse took a three-week vacation, these measures plummeted to where they were before the child was admitted to hospital. But, great news, the numbers spiked again when the nurse came back from vacation. Robert Sapolsky summarizes this beautifully:

To take a concrete, nuts and bolts feature of growth, the rate at which this child was depositing calcium in his long bones could be successfully predicted by his proximity to a loved one. You can’t ask for a clearer demonstration that what is going on in our heads influences every cell in our body.

Robert Sapolsky, Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers

It’s worth mentioning that growth hormones are secreted by the pituitary gland, a dangly pea-sized piece of meat at the inner center of the brain, which in turn is regulated by the hypothalamus just above. The hypothalamus, A.K.A. the big hormone boss, regulates stimulatory and inhibitory hormones, and given how central it is anatomically, it should be no surprise that this is an ancient feature of life. While the details of its structure vary, it’s found in all vertebrates, and scientists like Detlev Arendt have pointed out that even invertebrate animals show similar features, meaning the common ancestor is really ancient. It’s a core part of being human.

In a somewhat awkward but enlightening study by James Coan, women were placed in an fMRI machine with the knowledge that their legs would receive an electric shock at some point. It’s not easy to be chill in a situation like that, and surely enough, the threat made their right anterior insula, superior frontal gyrus, and their hypothalamus dance with dread. The right anterior insula is a big chunk of meat on the inside and deals with feelings that warn you of problems like thirst and pain, whereas the superior frontal gyrus is dealing with integrating experiences into working memory and deliberative thought. But that’s the least interesting aspect of it.

There were three different groups: the first group received the shock by themselves, the second group held the hand of a stranger, and the third held the hand of their spouses. As you might expect, there was a dramatic difference in how stressful the event was when they were able to hold their spouse’s hand, although it should be added that the effect was dependent on there being high marital satisfaction to begin with.

The results are what you’d expect, even if this was a small study. If the absence of a loved one at age eight ruins our ability to deposit calcium in our bones, it would actually be a bizarre discovery if it completely stopped having an effect after our eighteenth birthday. However, while the mechanisms in place during infancy still play an important part in adulthood and shape the working model of social relationships, there are some important differences in romantic partnerships, such as power balance. Sometimes a person might be offering comfort, and on other days, they’d be the recipient.

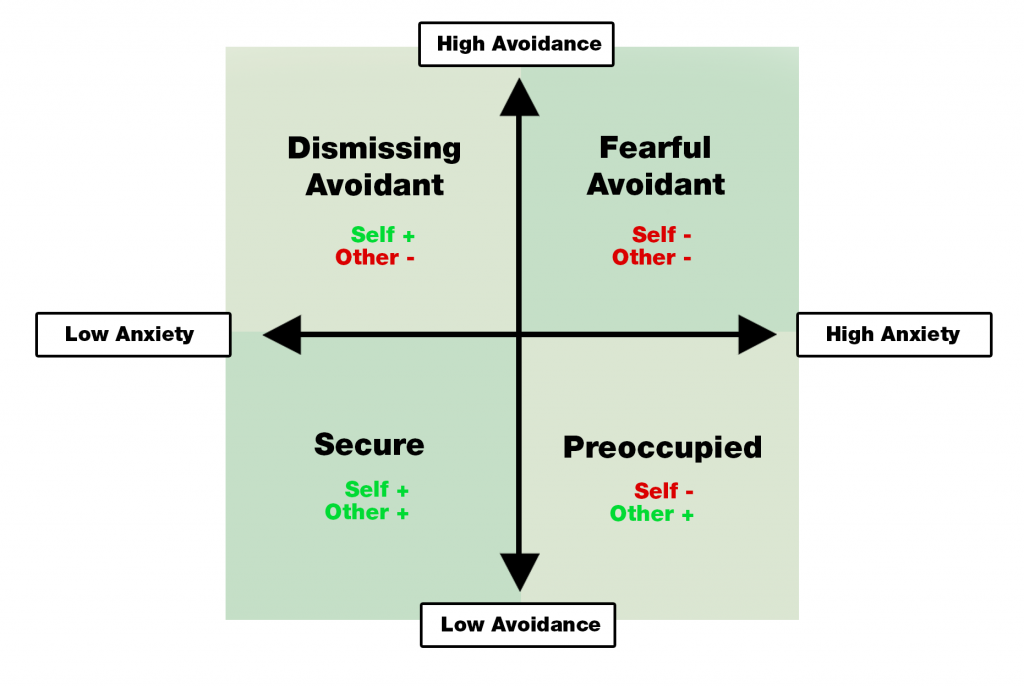

Over the years, Ainsworth’s categorical system has been updated to a dimensional measure of avoidance and anxiety, offering richer possibilities that account for differences in degree rather than kind:

The Good Ones Are Taken

There’s a degree of flexibility when it comes to the level of avoidance and anxiety in relationships, both for better and for worse. Plus, in many contemporary societies, children and adolescents tend to attach to their peers more than to their parents or older relatives (a historically unusual situation) which will also impact their attachment styles. And different situations will inspire more of either behaviour; a secure person might be walloped with severe life stressors or an abusive partner, triggering tendencies of avoidance and fear, whereas a clingy, anxious person might find themselves calming down with a secure partner and a stabler life.

It’s also worth mentioning that even though avoidant children only make a show of shutting down, and still feel just as strung out as the other types, there are some avoidant adults who learn to use this emotional castration to their advantage. Sure, secure people believe that the world is friendly and that they’re deserving of love, attracting secure partners as a result, and some avoidants believe the world is generally hostile, but they focus on enjoying their own company. Since attachment styles are built-in tools for responding to difficulty, there are some advantages to each behaviour, despite secure attachment being superior; after all, it helped the child get through their life in one piece. As another example, people with an anxious attachment style are more sensitive and perceptive when it comes to subtle changes in people’s moods.

People with low avoidance and low anxiety are much more likely to be in long-term relationships with people who have similar emotional profiles. Likewise, it turns out that the dating pool is disproportionately composed of people with avoidant behaviour, since they are more likely to detach from their partners and dissolve relationships. Sadly, there are some vicious circles. Since anxious attachment styles sometimes develop in response to avoidant attachment figures, the emotional distance will trigger behaviour that seeks closeness in the anxious partner, which will further exacerbate the avoidant’s belief that people are only out for themselves, making them withdraw even further, ramping up the anxiety of the other person.

Despite being a fearful avoidant, I’ve nonetheless tasted the sweetness of successful adult attachment, if only briefly. When I first began dating, I couldn’t even believe it was happening, as I’d assumed I was meant for solitude. The first night I made out with the woman I was dating felt like unlocking a secret of the universe. The grey, iron weight of the past and the jittery fire of the future dropped away, and I had the sense that suffering consisted of bitter waves in a vast ocean of delight. Due to my endogenous neurochemical fireworks, it made sense to me why the first epistle of John describes God as being directly experienced through love; it felt like tuning in to a vast, eternal electromagnetic field of peace that is always available, yet not easily received.

This energy made me feel much happier in my life, more willing to extend kindness to others, and I even began telling my parents I love them. The initial cause seemed hilariously simple to me—two bipedal monkeys holding each other and touching mouths—although I didn’t realize the deep-rooted attachment systems at work. Robert Weiss points out that attachment figures in adult life aren’t exactly protective like a mother or father, but they still foster ‘the attached individuals’ own capacity for mastering challenge‘, and generally provide a sense of security and safety.

The dark side of this, however, is that since attachment dynamics run so deep, even when two people are clearly not right for each other, the bond might still be forged, and even a wise separation can still feel like a catastrophic loss.

Hot Bible Thumping Action (18+)

J.C. was also hip to the biology of attachment theory. When the Pharisees asked him about divorce, he said:

Haven’t you read that at the beginning the Creator ‘made them male and female,’ and said, ‘For this reason a man will leave his father and mother and cleave to his wife, and the two will become one flesh’? So they are no longer two, but one flesh. Therefore what God has joined together, let no one separate.

Matthew 19:4-6

At the time, there was a big debate about permissible grounds for divorce, which Christ sorta sidesteps, remarking that divorce is a symptom of a much bigger problem, which is σκληροκαρδία (sklerokardia; sklero = hard/dry, kardia = heart, pronounced sklee-row car-dee-ya), adding that ditching one’s wife for anything less than unfaithfulness is a form of adultery. To my surprise, when his disciples hear this, they don’t make a vow to heal their hard hearts, but rather say, ‘fuggedabout it then, might as well avoid marriage‘. And again to my surprise, Christ doesn’t reprimand them, instead replying with ‘betchu can’t even do that right‘:

That conclusion cannot be taken in by everybody, but only by those who have the gift. There are some eunuchs, who were so born from the mother’s womb, some were made so by men, and some have made themselves so for love of the kingdom of heaven; take this in, you whose hearts are large enough for it.

Matthew 19:11-12

That last line about hearts reads like a bit of a sarcastic jab to me. After all, the chapter begins with the glowing reverence of marriage found in Genesis, followed by an explanation that Moses was forced to allow divorce as a concession for sklerokardia. If my heart was big enough, I wouldn’t be castrating myself to begin with. The interpretation of these few words is important, since it’s had some interesting consequences. There’s a Russian sect called the Skoptsy, where the hardcore male members remove their penis and testicles, and the female members lop off their breasts, labia minora and clitoris, using knives and red-hot irons. They were pretty popular (up to 100,000 followers) and had a reputation for working hard and making good money, but the powers that be ruthlessly cracked down on them, and they’ve waned in the last few decades.

We only need to look to the previous chapters to refine our understanding of the lesson we’re meant to learn. In Matthew 5 & 18, Christ calls for various kinds of mutilation, such as gouging out our eyes if they look at someone lustfully, or amputating our limbs if they cause us to stumble. What could he mean by this? Even taken figuratively, it’s quite the statement. What if the point he’s trying to make is that the integrity of our hearts is more important than a foot or an eye? This ties in to the project Paul was undertaking, a transvaluation of all values, as Nietzsche would put it, in that he wanted to flip the world on its head; God chooses what the world holds foolish to abash the wise, God chooses what the world considers weak to abash the strong, God chooses nothing so as to sanctify it and make it glow as if it were something. Nietzsche found this attitude towards life a dangerous one that he sought to stamp out; pedestalizing weakness keeps people sick, stunts their development and corrodes their instinct for growth and challenge. It wallows in weariness and builds resentment. All fair points, although there is a strange beauty to this ability to decouple from reality, and it might even be necessary for scientific discovery. After all, when Paul talks about the dead psyche, the dead soul, being sown as a body in the earth and having a pneumatic body becoming resurrected, he believes that pneuma is contiguous with heavenly bodies like stars on the dome of the Earth. Now it’s a commonplace to realize that we are made of stardust, that our bodies are actually composed of elements that were formed in space billions of years ago, but how counterintuitive can you get?

Anyway, Paul seemed to understand that Christ wasn’t to be taken quite literally, and focused on choosing to be a spiritual eunuch, since he snipes at those who literally castrate themselves in his letter to the Galatians. When Paul wrote ‘I wish you were all in the same [celibate] state as myself‘, it’s not as if he felt agape love all the time, functioning as a fully free, unattached and self-sufficient man. He clearly loses his temper in his second letter to the Corinthians, and in his letter to the Romans, he writes poetically about his psychological struggles, which I think just about anyone would relate to:

My own actions bewilder me; what I do is not what I wish to do, but something which I hate. […] Of this I am certain, that no principle of good dwells in me, that is, in my natural self; praiseworthy intentions are always ready to hand, but I cannot find my way to the performance of them; it is not the good my will prefers, but the evil my will disapproves, that I find myself doing.

Romans 7:15-25

[…]

Inwardly, I applaud God’s disposition, but I observe another disposition in my lower self, which raises war against the disposition of my conscience, and so I am handed over as a captive to that disposition towards sin which my lower self contains. Pitiable creature that I am, who is to set me free from a nature thus doomed to death?

Grave Matters

Paul’s final question at the end of Romans 7 definitely tests the limits of attachment’s benefits. In popular books on the matter, there tends to be a slightly cartoonish lens: “Trevor did not stay available for long. He quickly found a great partner and they have been together ever since. They traveled around the world, got married, and had a couple of kids. He is a wonderful father and husband.‘ Clients tend to be young, without any any sort of compromising illness, and death or mortality doesn’t come up. No doubt that for some people, in some circumstances, long-term coupling is a great choice, but not everyone’s luck is stellar, so what if there’s no intimate union to build a secure base and charge up the exploratory drive?

Paul might know, as he had a tough life. He was often homeless, went without food or water for long periods of time, received severe beat-downs, whippings, stonings, and got chucked into prison. Despite his devotion to missionary travel, he was quite intimate with poor physical health, and although he frequently prayed for God to remove the ‘thorn in his flesh’, he wound up having to live his whole life with an unspecified ailment so severe that he describes it as Satan torturing him. In his letter to the Galatians, he even expressed gratitude for the fact that they didn’t reject him on account of his illness. There’s also a line that implies he had poor eyesight, and he alludes to common insults he received on account of his ugly appearance and his voice, which means he may have had a speech impediment. Moreover, there’s compelling evidence from contemporary case studies of neurological disorders that suggests Paul had temporal lobe epilepsy, which would explain both the visions he describes in Second Corinthians and the conversion experience on the road to Damascus. And finally, let’s not forget that he considers himself a murderer because of St. Stephen’s death.

So he was a sick, ugly, epileptic, stuttering, homeless jailbird with murderous tendencies; quite a stack of woes. And despite all that, Paul asks people to ‘rejoice always, pray without ceasing‘ and ‘give thanks in all circumstances‘. Tall order, but that particular line from Thessalonians inspired some victims of Nazi concentration camps like Corrie ten Boom to be grateful despite being stuck in flea-ridden barracks. There’s also plenty of empirical evidence that it’s possible to positively influence neurological function through spiritual practice, although I’m sure everyone is sick of hearing about the benefits of meditation, so I’ll limit myself to some neat technical points.

Andrew Newberg has studied Christian centering prayer and Tibetan Buddhist meditation, finding that both groups, after many years of practice, were able to deliberately decrease activity in their parietal lobes, leading to a sense of timelessness and spacelessness. This experience was couched in the lingo of the respective religion, either ‘being in the living presence of God‘ or ‘entering a state of absolute awareness of the universe‘. Parietal lobes are roughly responsible for orientation, and sometimes, when a tumor pops up in that part of the brain, patients complain of different parts of their bodies becoming alien to them. In more normal circumstances, this sense of losing one’s self takes place whenever there’s an absorbing experience, like making love or watching a sunset.

Unexpectedly, while the parietal lobe activity is lowered, the thalamus activity increases during spiritual work. The thalamus is responsible for sending sensory information to different parts of the brain, including the frontal cortex, and we’d be missing the experience of consciousness without it. Normally the thalamus and parietal lobe are buddies; for example, they charge up during dream states and chill out during dreamless sleep. But during certain kinds of meditation and prayer, the thalamus activity increases while the parietal lobe decreases, strengthening lucidity while at the same time moving beyond concern for our particular self. Pretty neat, right?

One reason that one must pray without ceasing, however, is that negative life experiences are much more likely to get burned into the brain via the hippocampus, while positive life experiences are more likely to be forgotten. For evolutionary purposes, we’re much more sensitive and attuned to anything that’s going wrong, even if the vast majority of things are going right. In a neurological study from the 1960s, people had a wide variety of different parts of their brain artificially stimulated. You might expect the best feelings would be something like eating a delicious meal or intense sexual arousal, but apparently the winner was ‘frustration and mild anger’. Indeed, in the Ghatva Sutta, the Buddha describes anger as having a ‘honeyed crest and poison root‘.

This isn’t only an academic curiosity, since designers of social media platforms have admitted to exploiting negative triggers precisely because they are much more powerful. All the the most incendiary, outrageous and polarizing stuff tends to get signal boosted since it activates the limbic system much more directly than positive, peaceful stuff, which is why it takes a sustained effort to decondition ourselves. As always, Paul puts it memorably in his letter to the Philippians:

Finally, brothers and sisters, whatever is true, whatever is noble, whatever is right, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is admirable—if anything is excellent or praiseworthy—think about such things.

Philippians 4:8

But what about my grandmas? How does all this ameliorate their worry about me being doomed to bachelorhood? The answer is to out-grandma them using my patented Grandma Judo. I told them about a time when I had some rough side effects from some medicine, and my lungs felt like they were shutting down. I was too weak and disoriented to do anything about it, so I spent a few hours struggling to breathe. There were some moments where I wasn’t sure if I was going to come out on the other end, so I made a promise to myself, to God, the Universe, whatever was listening, to never take my breath for granted again. Earlier that day, I was feeling unlovable, ugly, weak and stupid, despairing about my loneliness and the crummy hand that I’d been dealt in life. But in the light of my basic biological functions being called into question, such concerns seemed pretty ridiculous.

Da’ud said, ‘O Lord, show me Your most hidden blessing!’

Al-Qurtubi

Allah replied, ‘Breathe, Da’ud. Who counts this blessing night and day?’

Of course, rejoicing in life’s little blessings is the most grandma-ish in the world, so they were on board when I explained this to them. In days of yesteryear I’d visit Nina for dinner on Thursdays and complain about my life, only to hear her never-ending refrain to be grateful for what I already have. It frustrated me to no end, and it never worked to hear. But while the Fruit of the Spirit (love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness) must be tasted, it can always be shared.

Judo SLAM!

Εἰρήνη πᾶσι

References

The marriage dilemma of involuntary bachelors: the case of China

Jews at Peace in Egypt, a Tale Told on Papyrus

Porneia: The Making of a Christian Sexual Norm

The Timing of Cohabitation and Engagement: Impact on First and Second Marriages

Evolutionary History of Hunter-Gatherer Marriage Practices

Shakuntala : The Mahabharata Story

John B. Watson – Psychological Care of Infant and Child (1928)

Attached: The New Science of Adult Attachment and How It Can Help You Find—and Keep—Love

Adult Attachment: A Concise Introduction to Theory and Research

John Bowlby, Attachment Theory and Psychotherapy – Professor Jeremy Holmes

From Heresy to Harm: Self-Castrators in the Civic Discourse of Late Tsarist Russia

Lending a hand: social regulation of the neural response to threat

Dating Over 40 Is Like Thrift Store Shopping. Joe DeVito – Full Special

How Our Childhood Shapes Every Aspect of Our Health with Dr. Gabor Maté | FBLM Podcast

Dr. Gabor Maté – Hold On To Your Kids

Giving Thanks in All Circumstances – Corrie Ten Boom (by Vance Christie)

Ruth Feldman’s brain imaging of parents

Why We Believe What We Believe

The Fearful Eye: Using Virtual Reality to Hack Fright

Not all emotions are created equal: the negativity bias in social-emotional development

Angry by design: toxic communication and technical architectures

Tafsir Al-Qurtubi – Clasical Commentary of the Holy Qur’an (Translated by Aisha Bewley)