My first strong opinion on having kids formed when I was 18. A guest on talk radio described people without children as biological failures, which sounded persuasive to my young ears thirsty for guidance. The scientific adjective meant my failure was objective, that I’d fail not just in society, but beyond that, at my core, my fundamental corporeal existence. I didn’t process it quite so precisely at the time, I just knew I didn’t wanna be a failure of any kind. Tapping in to the strength of the phrase, I used it in a conversation with a classmate and was pleased to see how easily it shut down opposition to being childless.

Mentioning the idea to my parents elicited delighted smiles of approval, maybe owing to the surprise that their teen son was really into having kids for some reason. The fact that reproduction was family approved, recognized by peers, and encouraged by prominent talk radioites meant having kids would be a safe bet for success in life.

Because of my allergy to loss and failure, I was blind to what exactly a winning vision would be, or in what sense biology is implicated in the value of a soul. Biological success might be objectively measured by the number of offspring, and by that measure, Genghis Khan was the most biologically successful man on the planet, a man whose name is now synonymous with cruelty, murder and rape. Some of my least favourite things.

It would be a while before I could develop these thoughts further, as I spent most of my time alone and didn’t put much value on relationships or dating. In fact, my enthusiasm for biological success faded through the years as the various hardships of life wore me out, and after six long years at art school (OCAD was famous for depressed students) I declared to a friend that I’d never have kids. This felt noble, since the whole idea of perpetuating the cycle of suffering by making more people seemed crazy, and for some reason most folks weren’t clued in to this obvious fact.

I’ve recently found that there are strains of Pauline theology, particularly appealing to young men & women, which are kind of similar. Corinthians has a tender and beautiful description of love which has moved me to tears at a wedding, but also tries to nudge readers away from sex altogether. In the era of Acts of Paul and Thecla, a young woman would essentially be a baby factory, required to pump out around 5 kids just to keep the city from shrinking. Since they were considered to be of childbearing age at 14, the ancient perspective of life was one of rapid death and decay kept at bay by a deluge of babies. Many of these young girls would have their children die in infancy, and often died themselves. It’s little wonder then, that girls like Thecla saw Paul’s message of chastity as one of liberation from this potentially lethal cycle.

Once I started to date and feel love, my anti-natal conviction became more diluted. That feeling of finding an intimate connection with another person was profound by itself, but the idea that there would be a new human life as a result of that connection was the most magical thing imaginable. All my personal projects seemed to pale in comparison to another beating heart that I’d be completely responsible for, whose presence was contingent on my decisions.

But rediscovering the beauty of having children was challenged again when my girlfriend told me that she was never going to have kids of her own, only adopt. I hadn’t put much thought into the idea before, it seemed bizarre to bring up another man’s child. To paraphrase Patrice O’Neal (RIP), I didn’t want some other guy’s balls walking around and giving me attitude. I assumed that the only way I could bear the difficulty of raising kids would involve full responsibility, to have their existence based on our biology.

So I started to ask myself, what if the idea of blood lineage is a spandrel of our mammalian past? What if we’re endlessly tricked into creating our own offspring through the vanity of resemblance?

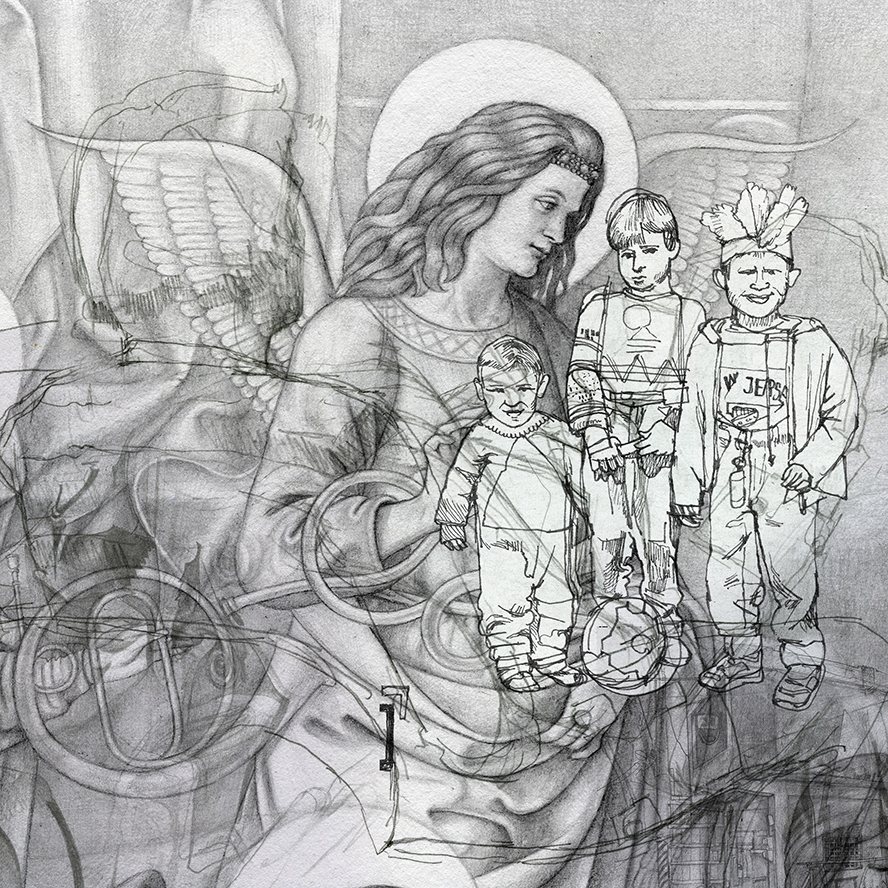

Maybe it’s both logical and moral to adopt, as there are many children in need of loving, stable parents. The endless thrill of beauty, music and dance that I live for is available for anyone with a roughly human body. What if the important things to transmit to children are curiosity, kindness, gratitude, resilience, discipline, patience—rather than a fraction of slightly altered genetic code? Well, As much as I might have logicked myself into adoption, the difficulties of working full-time made me doubt that I can take proper care of my own damn self. Listening to the experiences of working parents and watching shows like Workin’ Moms continues to humble my sense of just how much work is involved in the upbringing of a child.

I used to think that inventing Santa Claus was stupid and cruel, since it raises hopes only to shatter them later. But what if it’s a symbolic introduction to adulthood? After all, the story of Santa Claus suggests there are strangers who are completely fair, caring, reliable and exceptionally generous. Always will be. Now, this person isn’t exactly real, but he could be. With the right intentions, he can be simulated to a convincing degree, which explains civilization pretty well. That is to say, it explains (in ways a child could understand) the idea that we can all, in principle, get along by putting in the work.

Along with pondering the deeper social implications of Santa, my daydreams have often involved a hypothetical child that I’m guiding, where all my hard-won knowledge helps them leapfrog obstacles and continue my lofty goals. Yet I don’t remember a time in my childhood when I thought my parents knew better. They had all the power, sure, so it was wise to obey, but I never thought of myself as vulnerable and ignorant. Quite the opposite—I’ve felt like an adult my whole life and yearned to have independent power, miming it out in absurd details like drinking coffee and reading newspapers, the twin pillars of adulthood. Naturally, I’d get a double-double from Timmies.

And frankly, I had my wits about me (except for that one time where I nearly got hit by a car). No one had explicitly taught me about sexual predators, but I still had the intuitive sense that some adults were weird with regards to naked children. I assumed these broken people hid in plain sight, so I needed to stay alert no matter how good someone seemed on the surface. When I was ten years old, a family acquaintance in our apartment building offered to fix my broken GI Joe toys, and I was immediately suspicious; what’s in it for him? But I wanted those toys repaired, so I visualized how I would escape if he tried anything involving taking my clothes off or touching me, and planned to bolt no matter how rude he’d think I was. There was no question of simply staying away, I loved these GI Joes, and as they were from another country, getting replacements was out of the question. You should have seen them: one GI Joe had vibrant green fatigues with a strong brown beard, and the other Joe sported a futuristic (yet sensibly practical) grey jacket, plus deep ocean-blue pants highlighted with deliciously bright orange.

No trigger warnings here, it turned out he really just wanted to help me out and put a smile on a kid’s face.

And ain’t that what’s it all about? *cue Sarah Mclachlan music*

Really though, there’s something about making a kid happy that is remarkably satisfying. Spending time with friends who have toddlers feels like a brighter universe, especially if’s right after spending lots of time with older people. They love to jump, hug, run, roll, giggle, sing at the mall and dance on the sidewalk to the sound of fire trucks. Who wouldn’t want kids in their lives? Thing is, there’s some research which concludes that parents in developed countries are on the whole angrier, more depressed, more anxious and less satisfied with their lives than people without kids, and it extends to the point when children have grown up and left.

It’s kind of what you’d expect, given the mind-blowingly demanding job of raising a child, but there’s room to be skeptical. For one, the scientific tools necessary just don’t exist when it comes to quantifying something as muddy as happiness, contentedness, or satisfaction. Happiness might also not make sense as a goal, unless defined in some kind of Buddhist way which suggests equanimity and acceptance rather than a prolonged pleasant experience. Kids or not, life will eventually wear us down to the bone with infinite injustice, and our hearts will be steadily broken as those around us perish.

So what does biological success look like from this angle?

Listening in depth to peers with kids has made it very difficult to hold anything against my parents, as the level of attention and effort behind the scenes is almost obscene, it fills my internal sky with looming clouds of unfulfillable debt. Beyond a child’s universe of joy, there are sleepless nights where you watch them struggle to breathe, cry inconsolably for hours, refuse to eat the next morning, violently smack their siblings, break expensive things, and puke in the car. And yet, they remain a priority in your life.

The level of selflessness involved must bring parents closer to a sense of identity that acts as a sort of prelude to death, preparing them for a peaceful end while a newly created life glows with the joy of existence. It explains the previously baffling indulgence that parents sometimes give to their kids, like the variously poisonous treats or colourful toys that they only appreciate for the blink of an eye. But boy, do they appreciate it. So, the greatest success I could achieve is to be prepared to die, yet at the same time, hold on to a sense of awe and gratitude for the mystery of my biological reality. To peacefully straddle the mysterious chasm between animal frailty and human spirit. I’m not sure if being a parent will necessarily get me closer to that, but then again, in radio guy’s eyes, that’s just what a biological failure would say.