Giambattista Ludovisi (1898-1942) was an architect known for his grand scale, unusual severity, and staunchly anti-utilitarian approach to architecture.

He was born in Rome to Corrado Ludovisi, a university professor, and Maria Botelli, a homemaker who had some minor fame as a painter. Corrado was determined to have an intellectually gifted child, choosing to read to Giambattista every night with excerpts from the likes of Machiavelli and Nietzsche—the latter of which proved to be an enduring inspiration.

Maria regularly took her son on day trips around Rome to study its world-famous architecture, sculpture and paintings. Whenever he encountered work by Bernini and Caravaggio, Giambattista would sit and stare for hours.

However, as so often happens, puberty made Giambattista scarcely recognizable to his parents. As a teenager, he became reclusive and recalcitrant, sometimes disappearing for days on end without any explanation. Denouncing what he described as the decadent luxury of Rome, he began to write increasingly caustic aphorisms which eventually gave birth to his infamous architectural movement, Cuore di Pietra.

The manuscript for Cuore di Pietra was either lost or destroyed; either way, only a small selection survives thanks to its numerous detractors which give direct quotes in order to attack its ideas.

Aphorism 13, perhaps the most famous, introduces the name of his architectural movement:

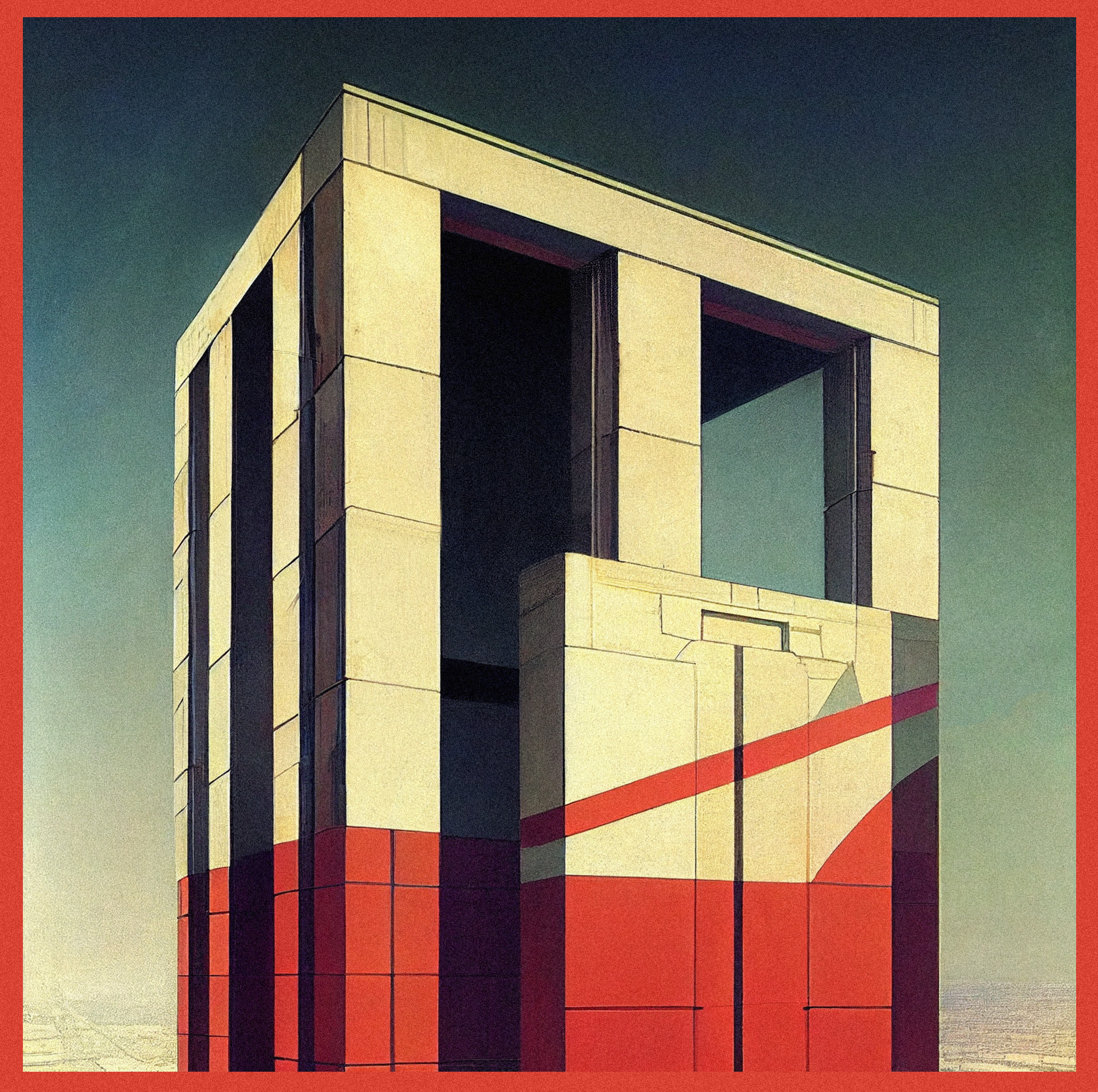

These aphorisms were richly illustrated with dream-like paintings of buildings with no discernible function. Take, for example, his Palazzo delle Prove, which imposes itself on the landscape as if by God-given right, unaccountable to man or beast—an eternal and immovable force:

But it would be a mistake to say that Ludovisi’s buildings serve no function.

Rather, it’s that he rejected workaday purposes which downplay his principal spiritual message:

This aphorism is the inspiration for his Tower of Blood (Torre de Sangue) and Pillars of Wrath (Pilastri Dell’ira):

At times he was explicit about the pragmatic dimension of his architecture, although in typical Ludovisi fashion, his ideas had an uncomfortably sharp edge. When introducing his Austerity Room (Stanza dell’austerità) and Hall of Truth (Sala della Verità) he warns that not everyone is welcome:

In some cases, Ludovisi is also shameless in describing his intent to functionally terrorize his audience, as in §63 where he introduces his Angle of Vengeance (Angolo di Vendetta):

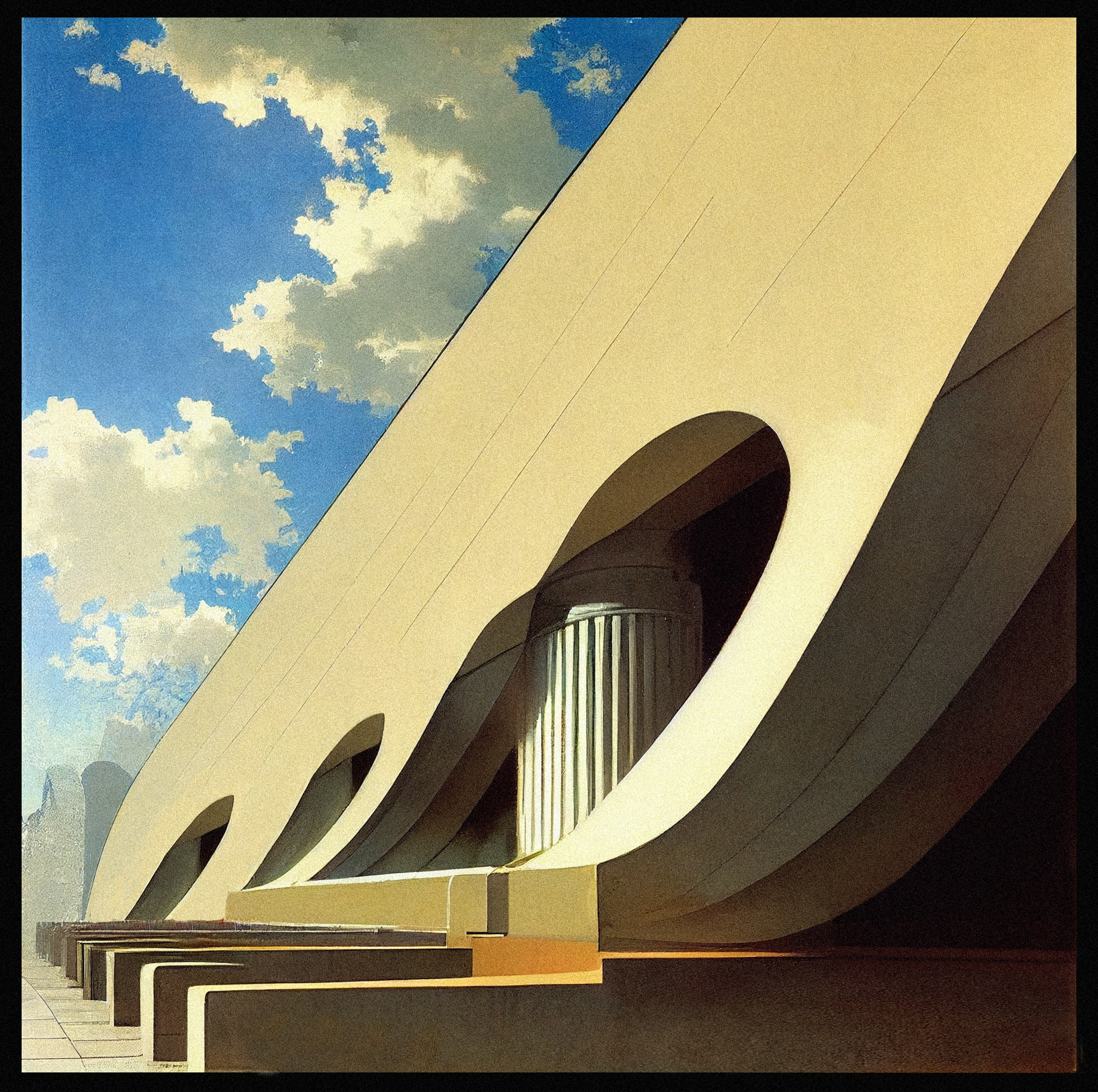

His most unusual work is his Curves of Anger (Curve di Rabbia) which blends large swaths of smooth, featureless concrete bending atop detailed columns:

Contrary to what we might expect, Ludovisi often remarks on the soothing aspect of his architecture. In §37 he explains:

Indeed, the bright, clean facade of the main entrance and the awesome scale of his Passage of Sacrifice (Passaggio del Sacrificio) evokes a sense of peace and stability that has captivated many students of architecture:

The later aphorisms which introduce works like the Site of Silence (Sito del Silenzio) are appropriately laconic, such as §91 which simply reads: ‘We seek silence and order.’

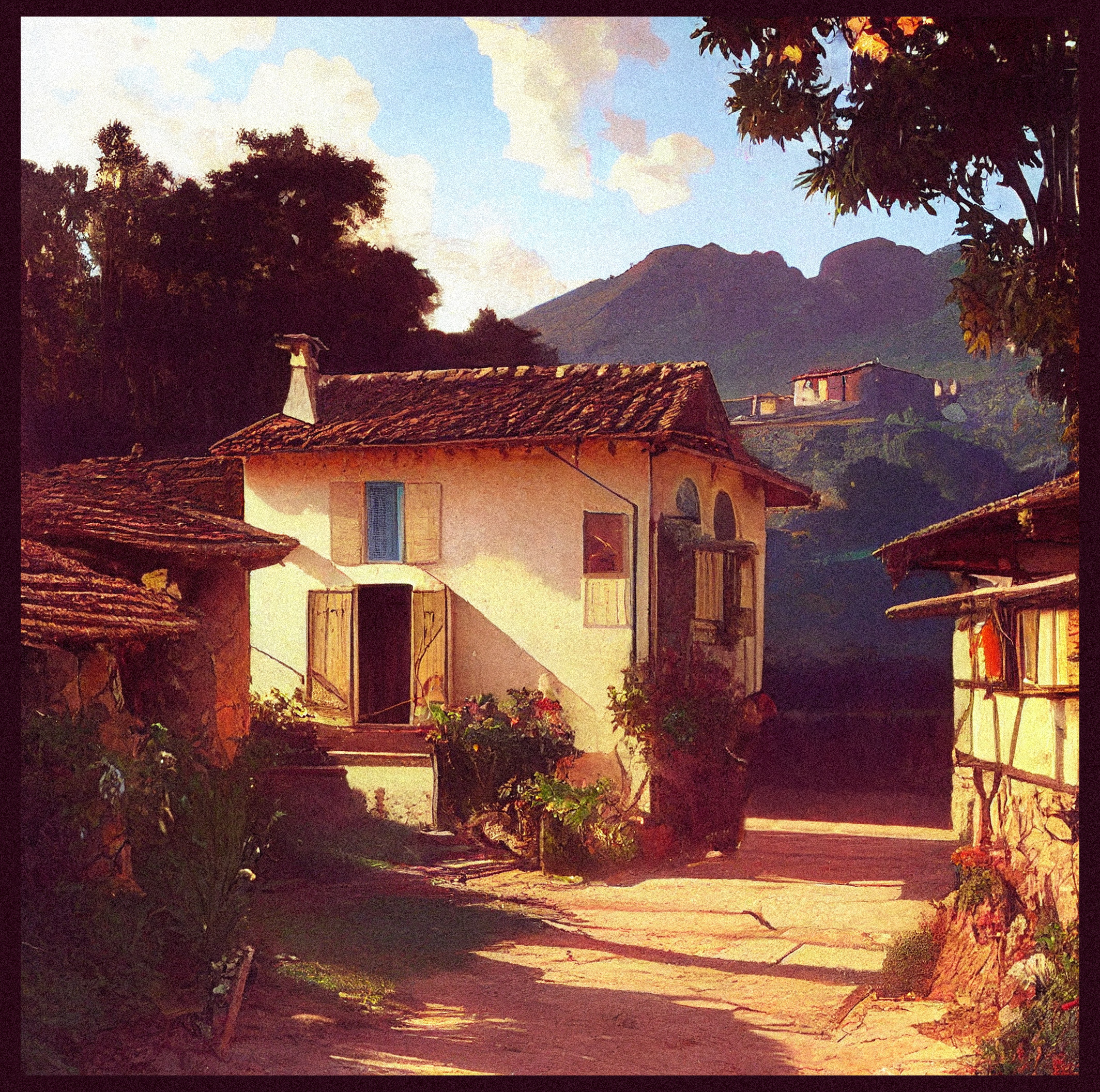

Tragically, Ludovisi suffered a severe health crisis in his late 20s, which forced him to abandon any hopes of furthering his career either as a philosopher or an architect. He retreated to a small home about an hour’s drive from Rome, where he died in his early 40s.