Abstract

This essay argues that there is such a thing as unhealthy art, and that its existence is a symptom of a broader cultural degeneracy. This degeneracy includes a valorization of ugliness, weakness, nihilism, irony, subversion, and most importantly, a destruction of family values and physical health. Although the concept of degeneracy is associated with extreme right-wing political parties like the Nazis, the fight against cultural degeneracy means embracing ideas that are simple common sense; beautiful things are nice, working out is good, having children and getting married is important. In summation, good art is beautiful and meaningful, a conclusion that is also explored in the light of AI-generated art.

Chapters

- Ugly Duckling Aesthetic Philosophy

- A Sketch of the Greco-Roman Spirit

- Modern Degeneration

- Symptoms of Aesthetic Disease

- Degenerate Art and Great German Art

- The Muscle Jew—Zionism and Healthy Art

- Instagram and Healthy Modern Art

- Forbidden Modern Art

- The Fight Against Degeneracy

1. Ugly Duckling Aesthetic Philosophy

My goal for this essay is to make a case for healthy modern art and diagnose the pathogens that threaten its health. To build such a rosy-cheeked aesthetic philosophy suggests that art can be unhealthy. That kind of suggestion runs against a common strain of thought we could call the Ugly Duckling Aesthetic Philosophy (UDAP). The story of the ugly duckling goes something like this: a bunch of duck eggs hatch, and one of them looks kinda strange. The strange one gets bullied and ostracised for being different, and in a fit of despondency he wanders off to cry. But just before his little tears have dried, he manages to find a group of swans and realizes he wasn’t an ugly duckling but a beautiful baby swan after all—a cygnet, they call it. The loving mama swan (a ‘pen‘) takes the misfit under her wing, and all’s well with the world. The moral is that an ugly duckling to one person is a beautiful cygnet to another.

In aesthetic philosophy, I translate this to something like: no matter how ugly and stupid your art is, it’s actually just a mismatch with your audience—fly your freak flag high and find your tribe! The Disney cartoon is excellent and worth watching since the cygnet is so adorable, but it’s a Disney cartoon and some things had to be left out or it would have been in bad taste and inappropriate for children. That’s because of infanticide—which is a common thing among birds for all the reasons you’d expect—food, predators, territory, mates. If a cygnet is diseased or too weak—say, it’s a slow swimmer—one of the parents will hold the cygnet by its neck and drown it, or, if they’re on land, crush and suffocate it. This is usually done by the male swan, the ‘cob’. Cobs will also kill any intruder it finds wandering in its territory, including cygnets.

A cygnet’s parents don’t directly feed it when it hatches, so it needs to have the instinct for complete independence from day one. If it doesn’t grow big and strong quickly, then it might be a slow swimmer, and, well… you know what happens to slow-swimming cygnets. So, if we were to revise the story of The Ugly Duckling to match the life of a real cygnet, we might say: hey kids, if you can’t keep up, that’s the end of you! Seems kinda like a brutal, scary message.

That kind of brutality is usually associated with fascists, a term which has been so drained of its meaning that you can just read as a synonym for ‘proud bully‘. No one really likes bullies, especially if they’re getting bullied, and there’s probably been a selective pressure against bullying since the dawn of humanity, since things could get too brutal. Some people have even argued that infanticide against the offspring of people high in reactive aggression has been crucial in domesticating human beings—modern foragers have infanticide rates ranging from 15-50%.

And the Nazis—the most infamous bullies of all—hated weird and ugly art, which is why they held an exhibit in Munich in July of 1937, where they attacked and humiliated what they called ‘Degenerate Art‘. But if fascists hate modern art, then people will instinctively take the side of modern art to avoid the reputational stain. They tend to say something to the effect of: modern art is really good, it’s actually the most important cultural innovation since, like, all of art, ever. And if you don’t like it you’re probably dumb, or a fascist, or both.

This isn’t too helpful in building a healthy aesthetic philosophy. We don’t have to brutalize the weak and diseased —one day, our own weakness will swallow us—but it would be helpful to focus on cultivating the strongest cygnets.

Imagine you have COVID symptoms and you visit two different doctors. The first one tells you to take time off work, get lots of rest, pop a couple of Tylenol, drink tea, try cough syrup, zinc, vitamin D, and so on. But the second doctor brandishes a gun, puts a bullet in your head and buries you in a shallow grave so you don’t infect anyone else.

Both of these doctors had the same facts in front of them—a sore throat, fever, and cough. Yet the two doctors dealt with it in two very different ways.

The UDAP approach would be to say: COVID is actually really good, since you learn a lot from being sick, and really it’s all a matter of opinion if it’s better to be sick or free from COVID.

There’s some truth to that, since getting natural immunity is probably a great way to prevent future infection. But ultimately, we want to be stronger and healthier, and take preventative medicine—probiotics instead of antibiotics.

Before going into symptoms, etiology and treatment, I’d like to begin with a sketch of the Greco-Roman spirit, a potent probiotic in fighting aesthetic disease.

2. A Sketch of the Greco-Roman Spirit

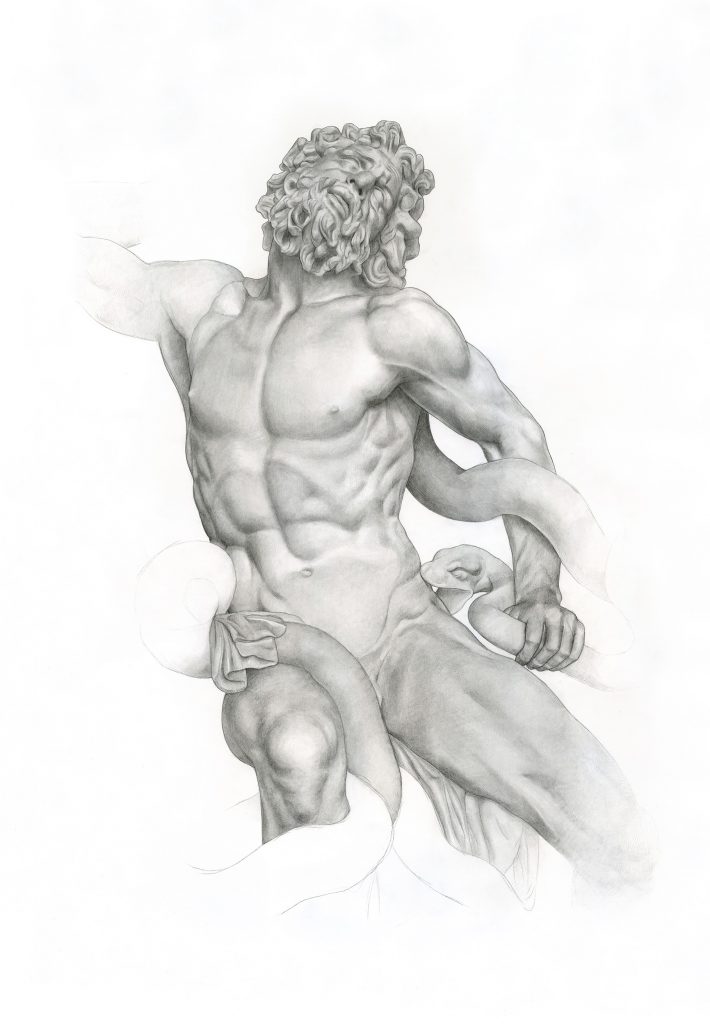

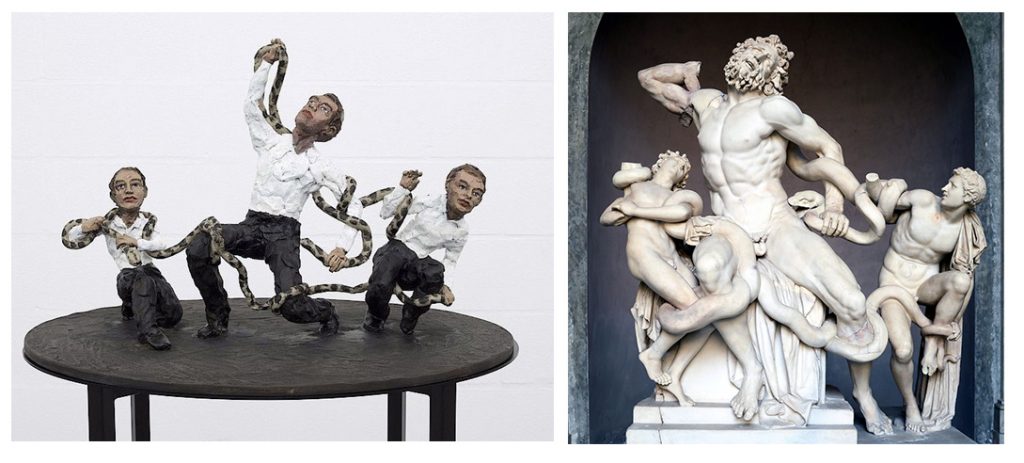

The Laocoön group was created about 2000 years ago by three Greek sculptors from the island of Rhodes—Agesander, Athenodoros and Polydorus. This is a clearly beautiful and memorable work of art, but the emotional meaning hit me like a thunderbolt while I was reading The Death of Ivan Ilyich by Tolstoy. Try thinking of it like this: you’re an upright citizen with a family and tribe that you’re devoted to. One day, some foreign enemies offer a huge peacekeeping gift that you suspect is actually something much more menacing.

But no good deed goes unpunished. For trying to do the right thing—for trying to save the lives of your fellow citizens, all of your hope is crushed before your eyes by a vastly powerful evil force.

Imagine all of the sacrifices you’ve made for your community, your children; all of the love you have for them, how they represent meaning, the future, your hope.

Now imagine that they are tortured to death in front of you.

And all you can see in your future is despair and death, which is moments away.

And yet, through this ordeal, the strength of your struggle, your resistance, is so beautiful that it’s worth immortalizing in marble to inspire millions for thousands of years.

Ah! *chef’s kiss* —Spirito Greo-Romano!

There are many variations on the story of Laocoön, some of which add all sorts of ambiguities to his moral character, but the point is that in the face of unimaginable suffering, beauty and meaning can still triumph. A hope inside of hopelessness. A heart in the heartless world. As Nietzsche puts it:

“Out of the original Titanic divine order of terror, the Olympian divine order of joy evolved through the Apollonian impulse toward beauty, just as roses burst from thorny bushes.”

3. Modern Degeneration

So—where has our Apollonian impulse towards beauty gotten us? Where is our Olympian divine order of joy? You’d think that after two thousand years, our art would be packed with meaning that flourished into a strong and healthy life-loving culture.

I think in some ways, the opposite has happened, and I sense some illness brewing—a degeneration.

There’s some empirical indications that people’s mental health isn’t great. A study in the Journal of Abnormal Psychology looked at about half a million teenagers and adults in the United States. What they found wasn’t great news, especially for the younger generations.

From 2005-2017, major depressive episodes increased 52% among kids aged 12 to 17, and 63% among young adults aged 18 to 25. The young adults also had a 71% increase in serious psychological distress. Remember, it’s social science so these are just rough general approximations—we might as well use warm and cold colours to indicate an increase of certain tendencies. But the message is pretty clear—it’s dicey out there for the youngbloods.

Maybe it’s the smartphone use, not sleeping enough, endocrine disruptors, industrial waste carcinogens, social isolation—the list goes on. Some older age groups stabilized and even showed improvement, so maybe a part of young people struggling is the difficulty of growing up in a complicated new world that’s unique in human history. The little cygnets understandably can’t keep up.

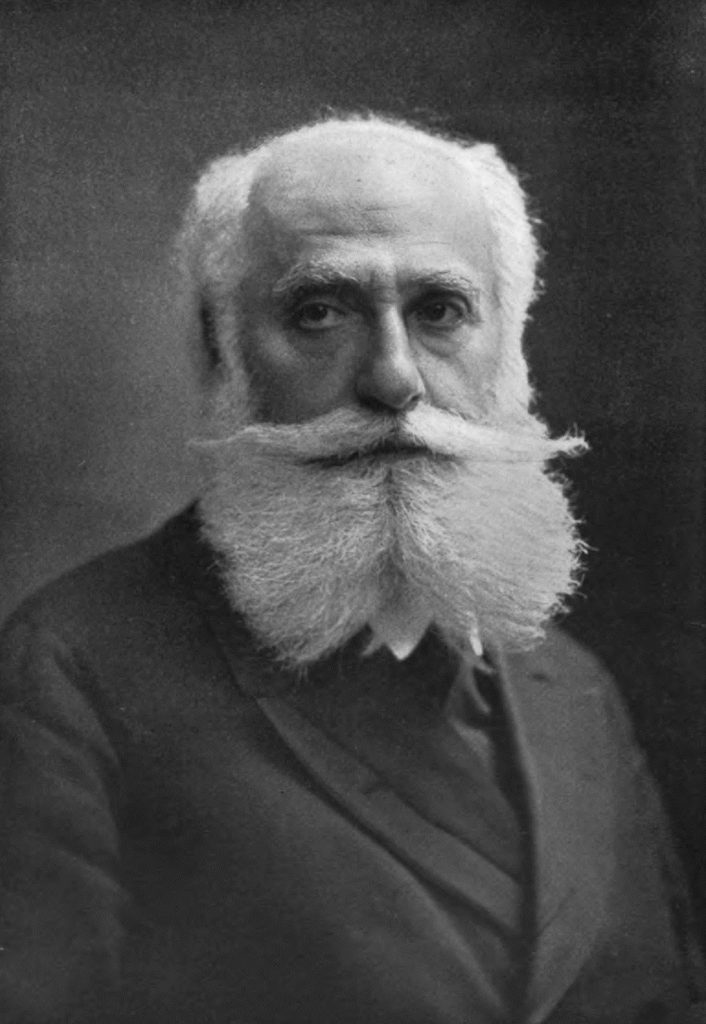

At the end of the 19th century, Max Nordau—a Zionist leader, physician, author, and social critic—published a book called Degeneration which looked at the way that people’s minds were being warped by the strange life of the city; he even mentions people’s obsession with being the main character and getting attention at all costs. Nordau classified anti-Semitism as a form of mental deterioration—that desperate attempt to pin the blame on an ethnic outgroup.

Nietzsche thought that anti-Semitism was especially stupid since he believed Christianity was a feeble outgrowth of Judaism, so being anti-Semitic and pro-Christian would be like proselytizing ethical veganism and running a factory farm.

Nietzsche also argued that the loss of God would be tough for some people to handle, even though it ultimately offers new freedom and creativity. He feared that in the vacuum of meaning resulting from the death of God in the modern world, people would become attached to one murderous political cause or another. He specifically saw in socialism a will to negate life, which is a common enough idea that it was satirized in The Simpsons as the slogan for the left-leaning Democratic party:

4. Symptoms of Aesthetic Disease

If the death of God and the will to negate life is a general social illness, and the mentally ill youngbloods find socialism more and more appealing, then surely we could see symptoms of this illness in contemporary works of art. Consider this sculpture near Yonge & St. Clair in Toronto which portrays a man holding a building :

This looks like an action figure that got accidentally chopped up in a blender, then painted over by a child to make it look new again. Whatever message this is supposed to get across, it’s not easy on the eyes.

When I first saw it, it made me wonder how two thousand years of technological and artistic progress—smartphones and antibiotics, Michelangelo and Canova—how that led to such a remarkably ugly sculpture when compared to Laocoön .

And the comparison to Laocoön is a reasonable one, since it just so happens the same sculptor created his own version of the classic:

Before I go on, I have to say that making good art is very difficult and requires a lot of dedication. If I hadn’t been encouraged as a kid, I never would have become a professional artist because so much of art consists of struggle and failure. So yes, encouraging people is good. But at a certain point you need to honestly evaluate your talents and options—Balkenhol’s work looks like a mediocre effort from a high school student. His work is appropriate as a silly gift for a friend—but not as a giant public sculpture.

We need to carefully distinguish the sin from the sinner, since creating degenerate nihilistic art is symptomatic of a bigger disease. Balkenhol is as much a victim of infection as he is a vector. Removing this sculpture will unfortunately not heal the underlying condition, just eliminate a symptom.

Part of the illness is political; section 37 in Ontario’s Planning Act gives developers zoning variances for more height and density if they offer community benefits such as public art. One percent of the developer’s gross construction costs go to this kind of public art, and in the case of this sculpture, Camrost Felcorp Inc. threw half a million dollars at Stephan Balkenhol and just let him do whatever. I’m guessing that it was a business investment for Camrost; what’s half a million in cost if it helps you make, say, five million in profit with adjusted zoning permits? And the government can pat themselves on the back for graciously helping the public—though of course, the public wasn’t involved in the art selection process.

Balkenhol was given no input or direction, nor does he seem capable of it himself; he makes it clear that the work is meaningless—or, to put it more politely, he invites the viewer to create a journey of their own meaning. After all, only a bully, a fascist would be so crude as to impose meaning on art and his audience.

Remember, UDAP!— all art is beautiful and valid.

Especially the ugly, meaningless stuff.

In fact, you might not even be able to handle the genius of nihilistic degenerate art. As Balkenhol explained in an interview: “Astonishingly enough, many beholders can hardly bear this openness.”

In other words, while he gets paid half a million dollars by the city, it’s up to everyone else to figure out what he’s doing.

This is a popular tactic used by degenerate nihilistic art: the work is described as a multi-valent mystery too brilliant to be captured from a single perspective, and the less you like it, the dumber you are.

Another option is to rationalize—to add sugary glazing to meaningless, ugly work by explaining that it’s actually bad on purpose.

It’s ironic… and subversive!

And by subverting, it’s transformed into a critique of society, which is what smart people do, after all. In art school I was taught critical theory, which, according to Horkheimer and Adorno, has no positive vision of the future; it focuses on attacking things because of all the disasters that have come about as a result of idealism. Instead of affirming and taking a risk, better to be on the sidelines and spit, insult, throw beer bottles—hopefully whatever remains will be worth having. Kind of like trying to destroy weak cygnets while refusing to think about what a strong one would look like.

A wonky sculpture of a guy holding a building standing on a bunch of blocks isn’t just an ugly, thoughtless piece of work, rather, it’s… a commentary on capitalism’s extractivist destruction, and colonialist expansion that degrades the colourful vitality of working-class people. Or maybe the coloured blocks are about how it tramples on Indigenous rights, or how queer pride is being trampled. You can fill in the blank here, but notice that whatever word salad is attached to a work of art, it’s anti-bully—anything that valorizes health, strength and beauty is suspicious, whereas a sarcastic attack is David’s slingshot to take down Goliath.

Here’s an example of the kind of work highlighted by the Haus Der Kunst in Munich in 2021:

This piece of work by Phyllida Barlow literally looks like garbage. But remember, it’s ugly on purpose. The museum’s website informs us that this is actually subversive and ironic. Here you could also add that it highlights capitalist extractivism, colonialism, indigenous oppression, and so on. Maybe—just maybe—an obsession with ironic subversion is symptomatic of a spiteful and corrupted spirit that is unable or unwilling to assert a positive, healthy modern art.

Remember the Democratic slogan as caricatured by the Simpsons—we hate life and ourselves. Beauty and strength are clearly ranked—some people are more beautiful and stronger than others, which means that there are losers and winners. And to say that some people are losers—well, that’s the bully’s domain, which we now enter by looking at the Degenerate Art exhibit.

5. Degenerate Art and Great German Art

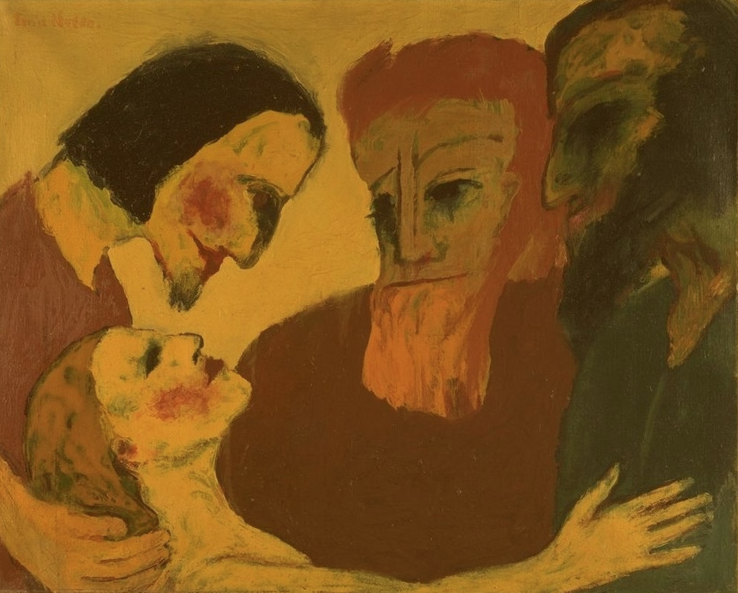

One interesting feature of the Degenerate Art exhibit held in Munich in 1937 is that having the right politics didn’t stop people from getting into trouble. Emil Nolde, who was both a Christian and a card-carrying Nazi, was humiliated in the exhibit for creating what was termed degenerate art.

And really, looking at this work, it’s.. well, really quite phenomenally ugly. As someone who’s seen a lot of different people struggle to learn to paint (myself included) Nolde was either extremely incompetent or very good at faking extreme incompetence. Being a good painter is very, very difficult, and it can be hard to accept that not everyone can be a winner when it comes to artistic skill. The Nazis were unnecessarily brutal, though, since they tried to stop him from making art or having access to any oil paint—the symptom was attacked.

Their method of suppression was that of a brutal doctor, but they weren’t just accusing people at random—they were looking for symptoms of weakness and degeneration, and trying to drown it by targeting individuals. You might be tempted to say that Nolde is challenging us to confront the radical Christian message of love that radiates indiscriminately, including sick, weary sinners. But all of his stuff is poorly done. He’s just not a good painter. And what’s worse is that this kind of ugly work was being purchased by museums—ostensibly for the public with the public’s money. To encourage this would be to encourage the financial and moral support of aesthetic disease, hence the outrage.

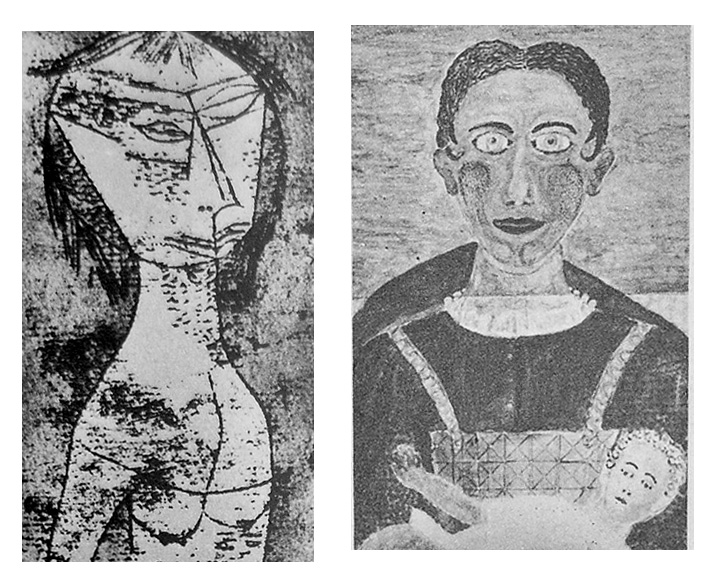

Sometimes the Degenerate Art exhibit tried to go past the plain ugliness of work and make an explicit connection to mental illness:

On the right is a painting by an institutionalized schizophrenic, with Paul Klee’s work is on the left looking even more deranged. The art historian move here is to either say that Klee was a mega-genius pushing art forward, or admitting that it’s deranged and ugly, but that’s a good thing because it’s an honest portrayal of modern alienation and pain.

In some cases, the latter argument is quite candidly made. Consider The Night by Max Beckmann—the words that come to my mind when looking at this painting include: horror, sickness, disease, muddiness, death, pain, misery, messy, swollen, ugly. Nothing positive.

As Stephan Lackner puts it:

Beckmann sees no purpose in the suffering he shows; there is no glory for anybody, no compensation […] Beckmann blames human nature as such, and there seems to be no physical escape from this overwhelming self-accusation. Victims and aggressors alike are cornered. There is no exit.

Or, to put it succinctly: He hates life and himself. This is somebody who has been defeated, who has been swallowed by the Titanic divine order of terror, who has been poisoned, whose excess venom is leaking into the drinking water. Should he be punished for exhibiting the symptoms of mental illness? No. Should the state fund, support and spread depictions of hopelessness and ugliness? I don’t think so.

Beckmann’s work was seen as something that could jeopardize the health of German culture, and the merciless response of the Nazis pushed some of the most mentally unstable people like Emil Kirchner to kill themselves. Such wanton cruelty and bullying inspired many people to punish the Nazis by fighting fire with fire—it’s been estimated that up to two million German women and girls have been raped by Allied forces, mostly Soviets, with something like a quarter million deaths.

As Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn wrote in Prussian Nights:

Twenty-two Hoeringstrasse. It’s not been burned, just looted, rifled. A moaning by the walls, half muffled: the mother’s wounded, half alive. The little daughter’s on the mattress, dead. How many have been on it? A platoon, a company perhaps? A girl’s been turned into a woman, a woman turned into a corpse…. The mother begs, ‘Soldier, kill me!’

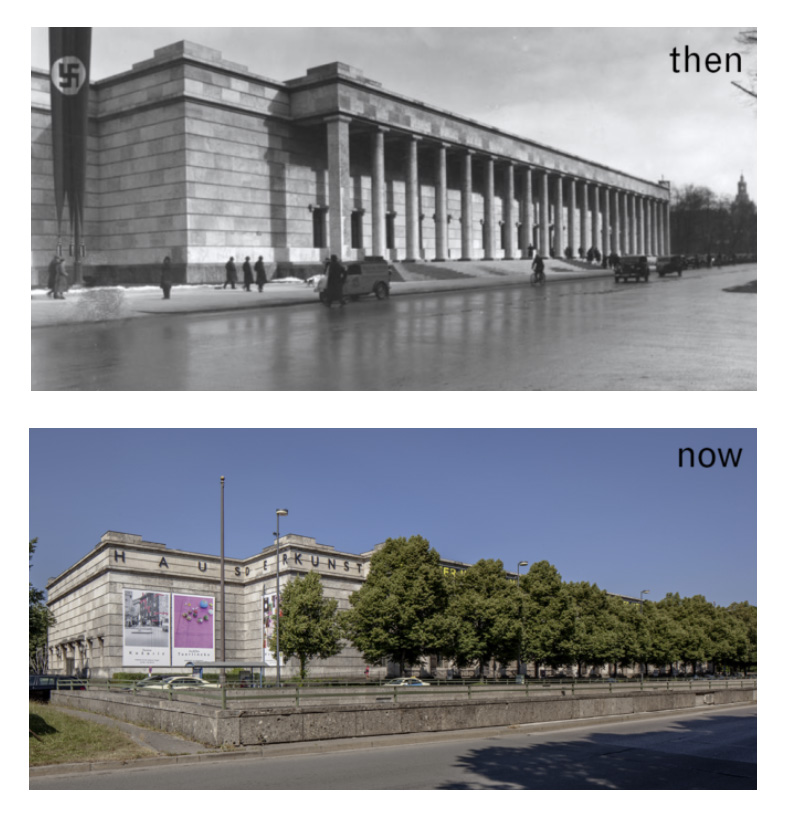

In some cases the Allies even admitted that they had no moral upper hand in their retaliation, such as their decision to destroy Nazi literature. Some longer-lasting and unusual punishment can be seen in the treatment of the art museum that the Nazis built in Munich. The Haus der Kunst which hosted the prestigious garbage sculpture mentioned earlier, actually began construction in 1933 when Hitler came to power, and finished in 1937. It was the first public building of the Third Reich and dedicated to the goddess of art with the intention to create a ‘building worthy enough to take a place among the immortal achievements of […] German artistic heritage.’

I understand the need to punish atrocities, the thirst for revenge, but I don’t think this is an effective strategy to combat political extremism and racist hatred. Enjoying a Greco-Roman portico doesn’t really lead to ethnic genocide—especially when this was clearly inspired by the Altes museum in Berlin, which is in plain view:

Art historians bend over backwards to heap ecstatic praise on everything that the Nazis hated, while attacking artists associated with the regime. Something to the effect of:

Oh, the Nazis called it degenerate? Well, actually, that happens to be one of my favourite things ever, it’s probably the greatest thing from the 20th century, if not of all time.

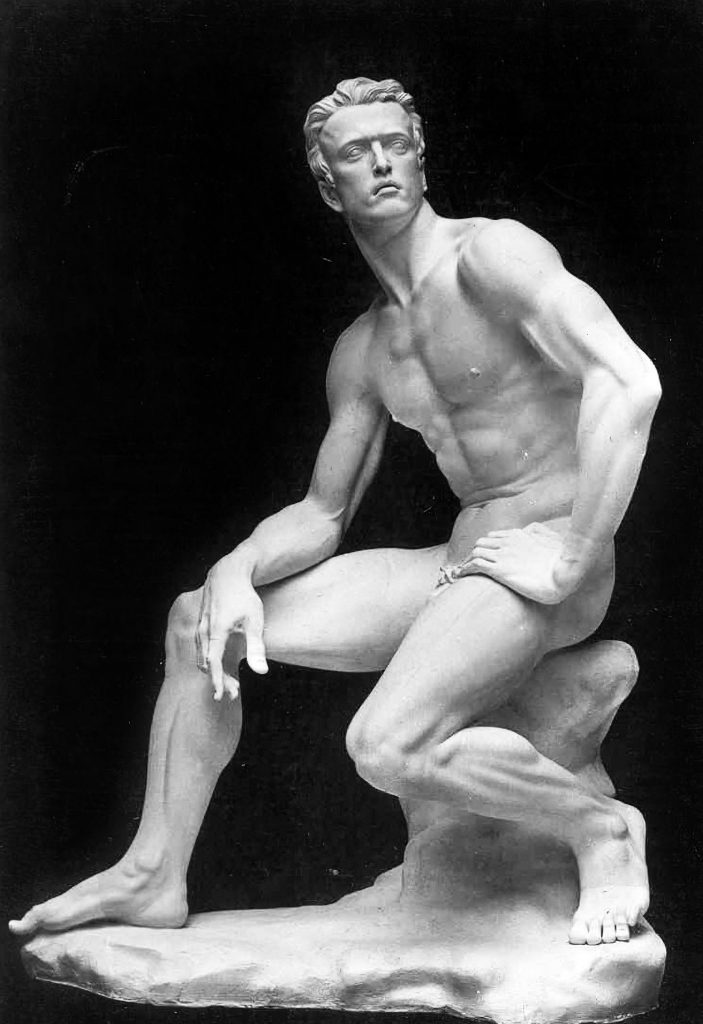

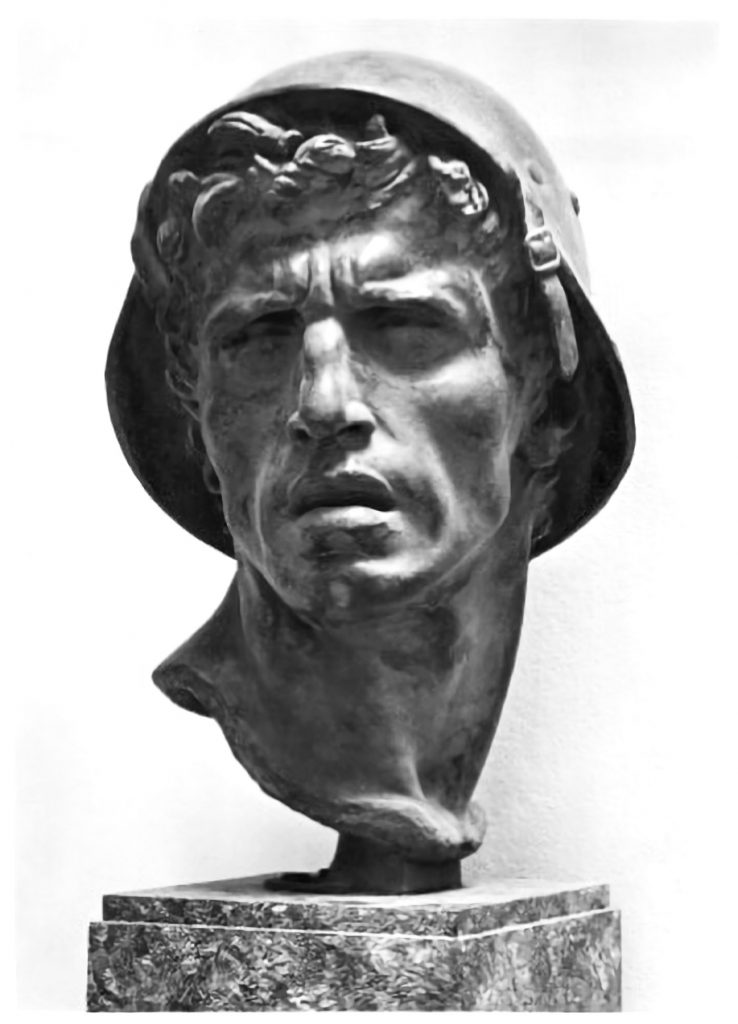

Art historians like Ursel Berger called Arno Breker a non-artist, probably because he was Hitler’s favourite sculptor:

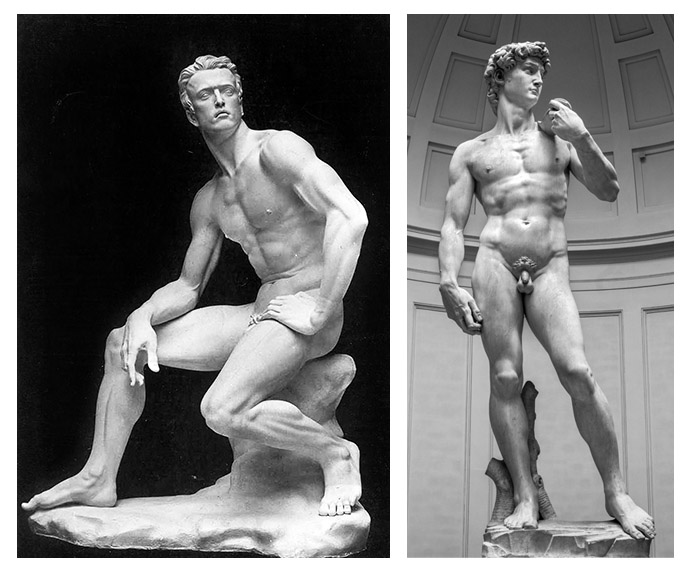

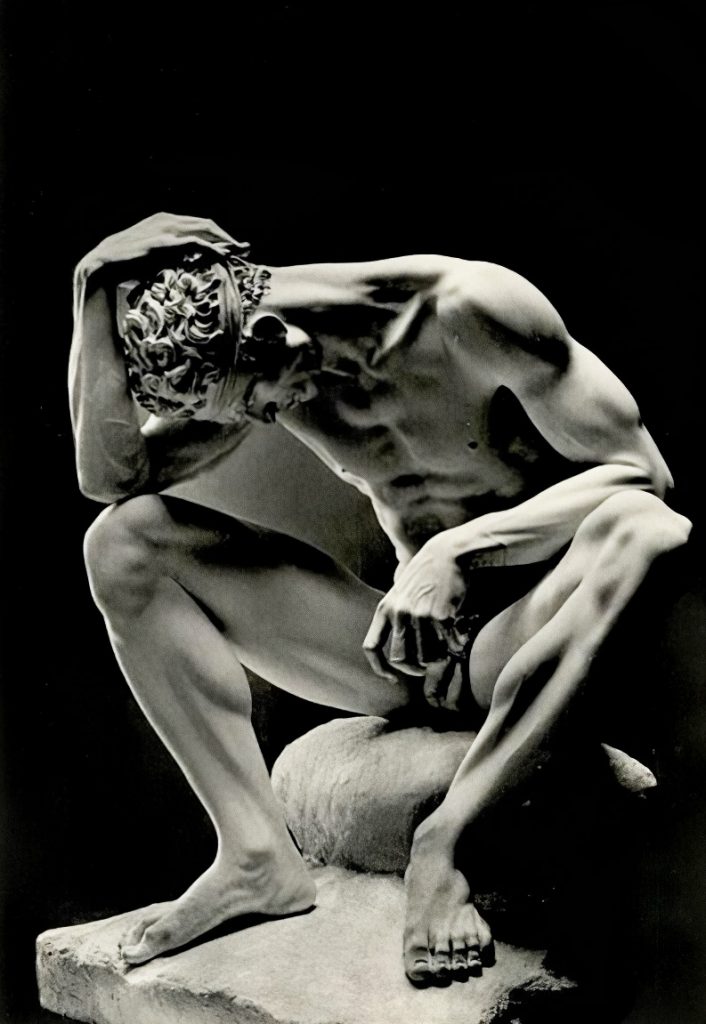

If you took Arno Breker’s Berufung—meaning vocation or calling—and put it next to Michelangelo’s David, it’s hardly apparent that these are in totally different categories of quality.

There isn’t really a significant difference in the way that male beauty, strength, pride, and discipline is admired. And Breker explicitly described such things as his artistic ideals:

What is the greatest miracle of creation?

Man!

Man in his most perfect and ideal form.

Man is the crowning achievement of creation. To form man ever anew? To recreate creation is as old as mankind itself: The unity of a spirit and form achieved a new representation of mankind in the art of antiquity. The works of the sculptors of that time still hold us in their spell. The heights and depths of their century have not been able to divert me from remaining true to the perfect, the ideal. I strive always for the highest form of perfection in sculpture. The variety of creation among human beings is infinite. Beauty of form, harmony of soul, spirit, and body is found not only in Europe; it exists on all continents. The images of man which I create are not idealized. They embody ideals and characteristics which are worthy of all men: human dignity, peace, respect, friendship, tolerance and freedom.

Sounds pretty nice—even sentimental. But some folks are nonetheless afraid of praising his work lest they be associated with a crazy cult that advocates murdering innocent people based on immutable characteristics. Not only has 90% of Breker’s work been destroyed, but exhibitions of his work have been mired in controversy and blocked by angry artists. A coalition of 30 artists in Schwerin have protested the exhibition of Breker’s work in their town, and Klaus Staeck, the head of the Academy of Arts in Berlin, canceled his own show in protest.

Elizabeth Berkowitz pointed out the unfortunate moral panic surrounding this kind of artwork with compelling honesty when she attended a show that had both Degenerate Art and Great German Art side-by-side. She heard people conspicuously dunking on the Nazi art by calling it bad and cheesy, and I like how she summarized it:

“‘We,’ as contemporary, enlightened placeholders for our 1937 counterparts, attempt on the victims’ behalf to take on the enemy, the Nazis and their accusations of degeneracy, and to treat them with the same contempt as they treated “us.” We try to see the world within their black-and-white binary, albeit with the roles triumphantly reversed. Perhaps with further historical distance, such reactions will be tempered. Until then, contemporary responses to the 1937 Degenerate Art Exhibition will continue to adopt the position of winning easy victories in the never-ending battle against the past.”

The never-ending battle against the past. I love that.

And what exactly did Nazi ideals stand for? Berkowitz explains it like this: “narratively straightforward, naturalistic, and, in many cases, directly illustrative of not only the ideal Aryan bodies but also of National Socialist agendas of health, values, and family.” That seems to be the opposite of Balkenhol’s sculpture, which represents a turn away from health, family, beauty, bravery, striving, passion, perseverance. It is purposefully ugly.

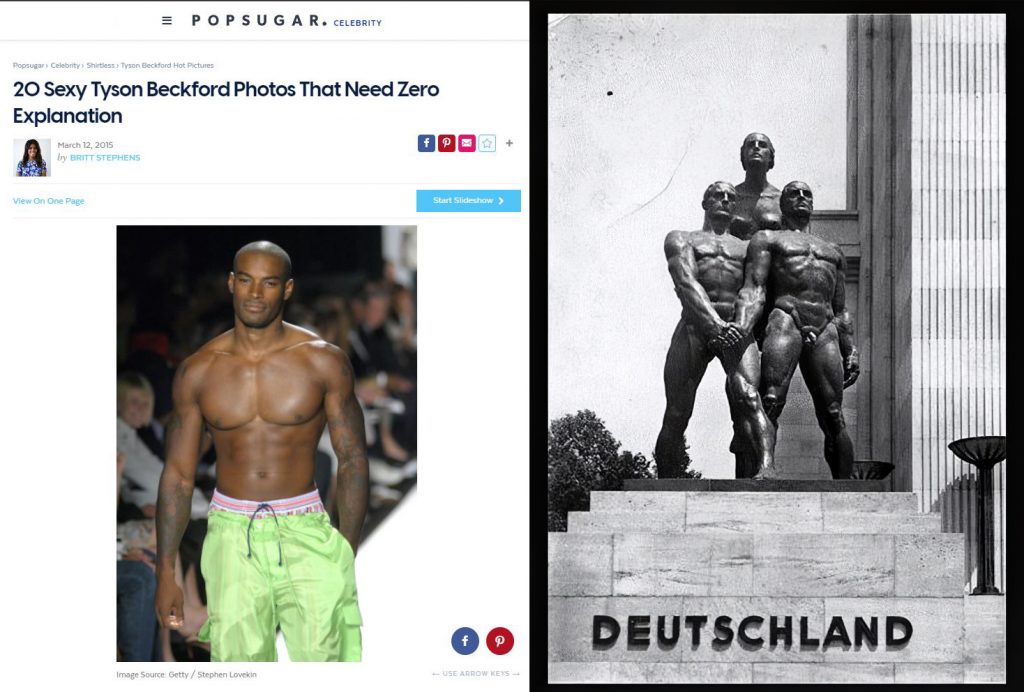

But contrary to Berkowitz, I find it strange to see Josef Thorak’s sculptures being described as examples of Aryan ideals. Am I the only one who notices that their skin is often… very much not white? I was under the impression that having light skin is important to be considered an Aryan. When I look at Comradeship by Thorak, I think of Tyson Beckford, not Alexander Skarsgård.

An appreciation for dark skin is hardly new to art in Munich; in the Cathedral of Our Dear Lady on Frauenplatz street, there’s a sculpture by Hans Krumpper from the early 17th century which doesn’t look like a veneration of light-skinned people to me:

But back to Beckford. Consider the title that Britt Stephens used in her article: 20 Sexy Tyson Beckford Photos That Need Zero Explanation. Remember what Berkowitz said about narratively straightforward artwork? Well, apparently, being direct has come to be associated with fascism.

In the 1993 documentary ‘Degenerate Art’, Robert Hughes admits that Nazi art is well done:

“What it has on its side is a certain kind of technical virtuosity which is undeniably there and which people certainly found attractive, and you know, I dare say people still do.”

But he attacks it by saying that it’s too easy to understand:

“Anybody can understand a whacking great surfer with giant pecs holding up a sword!”

Clear communication—another fascist horror!

But Hughes does make an important point, which is that Nazis were sensitive to degenerate art because they could feel the illness in themselves. Take this quote from the diary of Joseph Goebbels, one of the craziest of them all:

July 17, 1924

I’m so despondent about everything. Everything I try goes totally wrong. There’s no escape from this hole here. I feel drained. So far, I still haven’t found a real purpose in life. Sometimes, I’m afraid to get out of bed in the morning. There’s nothing to get up for.

This reads like a Gen-Z Twitter feed, but more importantly, it shows someone mourning the death of God. Goebbels was sickly from birth—as a child he had lung inflammation and a deformed foot. He tried to fix the latter with surgery but it didn’t go well, so as a result, he had to wear a metal brace and special shoes like a total weenie. His beloved high school crush dumped him which made him suicidal, and his attempts to make money as a writer failed, forcing him to work crappy jobs to survive. Goebbels had socialistic leanings, which would fit the whole ‘hating life and yourself‘ caricature, and although he was drawn to Hitler’s charisma and conviction, Goebbels was shocked and upset to hear Hitler describe socialism as a Jewish creation. However, after Hitler set up a meeting with him and other leaders of the socialistic opposition, Goebbels was completely won over:

“Such a sparkling mind can be my leader. I bow to the greater one, the political genius.”

Having found a sense of belonging in a political party, he completely devoted himself to The Cause and The Leader. At one point he was banned from giving speeches, since he riled people up to the point that they began attacking political enemies on the street. He founded the newspaper Der Angriff—The Attack—which led to dozens of libel suits since he would just say anything to slander his targets.

After the Nazis were given control of Germany, Goebbels was appointed to the Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, but the Nazi party didn’t have too much public’s support, so Goebbels ramped things up further; he was instrumental in boycotting Jewish businesses and burning forbidden books—icons of fascistic brutality. Life magazine in the late 1930s said that Goebbels ‘likes nobody, is liked by nobody, and runs the most efficient Nazi department.’

6. The Muscle Jew—Zionism and Healthy Art

Goebbels was an extremist, but most people didn’t like so-called modern art—by which I mean all the ugly, weird stuff. The artist guilds in Munich didn’t care for it, and an exhibition in 1930 had about 5% of work that deviated from traditional styles. And even though the Nazis linked Judaism to degeneracy, some Zionist thinkers had a remarkably similar attitude towards the modern valorization of ugliness and weakness. Max Nordau argued the necessity of highlighting ‘discipline, agility and strength‘, creating ‘healthy, physically fit, nationally minded and militarily strong Jews‘. Nordau explains:

Our new muscle Jews [Muskeljuden] have not yet regained the heroism of their forefathers… to take part in battles and compete with the trained Hellenic athletes and strong northern barbarians.

As quoted in Todd Presner’s book Muscular Judaism

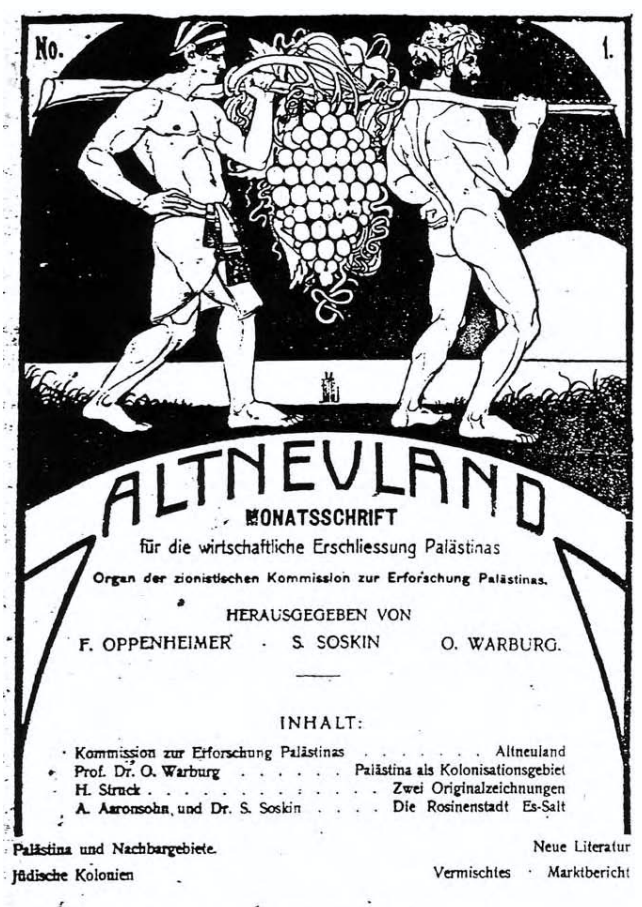

Artists like Ephraim Moses Lilien, dubbed the first Zionist artist, used Hellenistic art to create the ideal Jewish body, as seen in this illustration of Jews migrating to Palestine:

The grapes here refer to the Book of Numbers where the Israelites are on the way to the Promised Land. God tells Moses to round up soldiers so the Israelites can conquer the Promised Land, and they manage to gather over half a million men. Moses sends out spies to find out whether or not the Canaanites have good fortifications, strong warriors, fertile soil, and good fruit. They return with some beautiful grapes and explain that it’s a lovely place flowing with milk and honey, but it’s also well fortified with giant tough guys, so there’s no way they could conquer Canaan.

God is furious at this lack of faith and condemns the unbelievers to suffering and death. God is generally quite brutal throughout the Book of Numbers and routinely strikes down people who complain, disobey or lose faith—remember, the cygnet that can’t keep up gets drowned. He is also merciless with the enemies of the Israelites, instructing a massacre of the Midianites, the torching of their towns and the enslavement of children and virgin women.

In Lilien’s illustration, the Jews seem strong and powerful, as if their opponents are no match for them, or that they’ve already conquered the Promised Land, with the grapes serving as a delightful spoil of victory.

Lilien drew this picture for a journal called Altneuland, or The Old New Land, which was established to plan for the Jewish colonization of Palestine. Altneuland is a reference to a book written by Theodor Herzl in 1902 which sketches out the Zionist utopia populated by German-speaking Muskeljuden. It follows Friedrich Löwenberg, a young Austrian intellectual who’s fed up with European decadence and decides to live in a remote island to get away from it all. On his way to the Pacific Ocean, he stops over in Palestine, and finds a ‘desert wasteland’ that’s sparsely populated. After about twenty years in his island paradise, he decides to go back, but again, he stops over in Palestine. And whaddya know: everything has changed into a Zionist dream—a Jewish organization named The New Society has taken power, and Palestine has become a technologically advanced, multicultural and multilingual place where everyone has the same rights despite their ethnicity.

When Herzl’s book was translated into Hebrew, the title given was Tel Aviv—tel, meaning ‘ancient mound’, or ‘old’, and aviv, meaning ‘spring’ or ‘new’. Hence, Old New Land. When a new neighborhood was established in Jaffa in 1909, Tel Aviv was its chosen name based on Herzl’s book, and it has eventually grown into one of the most important and powerful cities in the Middle East.

There’s only one Arab character in Altneuland called Rashid Bey, and Bey makes it clear that Arabs would be happy with Jews running the show since they’d raise the standard of living. There would be no war or armed forces necessary, since The New Society wouldn’t encounter opposition when they went around buying up land from Arabs.

Reality has proven to be a lot more complicated than this plan suggested, but Nordau’s emphasis on discipline, physical fitness, military strength and national pride seems to have been an influence for Israel forming one of the best armies in the world. Since service is mandatory and very challenging, a lot of Israeli teenagers go to training camps to toughen up before service.

As the Photographer Oded Balilty explains:

[T]hose who train to join the Navy are sent in the water when it’s cold weather. They go in and out, and at the same time the instructors are asking them questions about the history of Israel to see if they’re focused and if they are mentally stable. It’s very intense. [The instructors] want to simulate the tension and stress that soldiers are under in the military.

Aside from the complicated political implications of Israel’s military actions, I think Balilty’s photography is beautiful, healthy art. It promotes pride, cooperation, strength, courage in the face of adversity, historical consciousness and meaning. One of the striking things about Nordau’s idea of Muskeljuden is how similar it is to Hitler’s reflections in Mein Kampf. Nordau urged Jews to join athletic associations and claimed that training in gymnastics is essential for a healthy Jewish race. He wanted a return to the ‘strong chested, tautly-jointed, boldly-looking men‘, and ‘the physical development of strength as well as beauty‘. He wanted to teach ‘manly discipline, reciprocal adaptation to different personalities, and carefully constructed combinations of many efforts leading to a single common goal‘.

With that in mind, consider Hitler’s argument about gymnastics in Mein Kampf:

Our system of education entirely loses sight of the fact that, in the long run, a healthy mind can exist only in a healthy body. This statement, with few exceptions, applies particularly to the broad masses of the nation.

[…]

Thus, in every branch of our education, the daily curriculum must occupy a boy’s free time in useful development of his physical powers. He has no right in those years to loaf about, becoming a nuisance in public streets and cinemas. […] Our school system must also rid itself of the notion that bodily training is best left to the individual himself. There is no such thing as freedom to sin against posterity, and thus against the race.[…]

The exclusive intellectualism of education among our upper classes makes them incapable of defending themselves, let alone making their way in life. In nearly every case, physical weakness is the forerunner of personal cowardice.

[Source]

7. Instagram and Healthy Modern Art

If we have bipartisan agreement between Zionists and Nazis on the necessity of physical health and military strength then why isn’t this more prevalent in modern art? If you look at modern art as something exclusive to gallery spaces and museums, you would think that we’re doomed to ugliness, nihilism, irony and subversion. But if you look at more popular outlets for artistic expression, the healthy Greco-Roman spirit comes shining through with the greatest modern artist of all: Cristiano Ronaldo.

Pictures like these have around 10 million likes, and Ronaldo has almost half a billion followers on Instagram, second only to the official Instagram page. His body is a work of elegant art—he’s lean and symmetrical but in a natural and functional way. He gets help in sculpting this body from a team of highly trained medical professionals that give him finely tuned nutrition and training programs. His body also carries an inspirational and meaningful story—a testament to the Greco-Roman spirit of beauty blossoming in the face of adversity.

He was born to a poor family with an alcoholic father and a mother who wanted to abort him because she could barely take care of the three kids she already had. The doctor refused to perform the abortion, and Cristiano Ronaldo was born. There’s some Roman flavour here—remember that Romulus, the founder of Rome, was conceived by a woman who was raped and thrown in prison, while he and his twin Remus were left for dead as infants.

Through discipline and focus, Ronaldo not only escaped substance addiction and poverty, but became one of the greatest athletes on the planet. He’s a role model for children since he regularly donates blood, gives to charity, stays away from booze, and focuses on providing financial and emotional support for his family. In Nazi Germany, the Reich Association of Large Families, along with the National Socialist Cultural Committee, gave prizes for ‘artistically exemplary representations of genetically healthy families with many children‘. They added that this is ‘one of the most demanding themes to which contemporary painting had to address itself‘.

Ronaldo pretty much nails it here with a picture that has almost 20 million likes:

Sure, the composition is wonky, the lighting is awkward, the camera lens is distorting people’s faces—but that makes it look less like a sterile artificial photo shoot and more like an organic scene at home, although I’m sure they spent some time getting ready. I especially love how soft and welcoming the colour palette is—soft beiges and pinks with little splashes of vibrant, wild colour in the rambunctious little boy’s clothes. They look comfortable, healthy, beautiful, and prosperous. The Reich Association of Large Families would have surely given them a prize. And remember the summary of Nazi artistic ideals provided by Berkowitz: narratively straightforward, naturalistic, directly illustrative of ideal bodies, focused on health, values, and family.

And what better way to promote both masculine beauty and tender compassion than this picture of Ronaldo with his newborn daughter Bella Esmeralda?

I can hear the art historians already—this is too easy to understand! Sure, it’s beautiful, it’s meaningful, it fills the viewer with hope for humanity, demonstrates the importance of love and compassion and family, the preciousness of life, the sacrifices that parents make—blah blah blah. But where’s the ugliness, where is the vagueness, the irony and subversion? Where is the attack, the smirk, the scoff?

Luckily, most people recognize that this is healthy art.

Ronaldo’s wife Georgina Rodriguez posted a picture of Bella which got 2 million likes in an hour, and you can see why:

It’s so cute and hopeful and happy—what’s better than a healthy, comfortable baby smiling with joy? I’ll even forgive the garish branding on her clothing. That smile—my God! It’s especially beautiful considering the fact that Bella’s male twin died, which Ronaldo described as the greatest pain that any parent can feel, adding that ‘the birth of [their] baby girl gives [them] the strength to live this moment with some hope and happiness‘. That’s what this image exudes—hope and happiness in the face of tragedy and struggle.

8. Forbidden Modern Art

You might think that anybody can see the value of art oriented around family and children—that is, aside from those who hate life and hate themselves. However, I want to bring up a curious case of forbidden art in this vein—namely my own. Now you might wonder, what kind of weird Nazi stuff was I making to get banned from from one of the biggest art communities online? The r/art page on Reddit has over 20 million members with thousands browsing at any given moment, but it’s strictly moderated by a small group of about ten people. When I posted this portrait of me and my cousins, Park Boys, it was removed and my account was permanently banned (since lifted after pleading with a more level-headed moderator). Any attempt to subvert this ban would lead to being banned from the entire site.

This portrait was done using style transfer technology, where you select a painting and blend it with a photo using different parameters, which turned out to be unacceptable since ‘computer generated art‘ is forbidden from the community, and calling it digital art is misleading people into thinking it was done by hand. As one of the moderators explained: ‘It’s like a chess computer playing against a human chess player. It’s both chess, but the computer doesn’t get to play on a regular chess tournament.’

This could easily describe photography—how could we allow someone to press a button on a machine instead of spending hundreds of hours learning how to oil paint? Surely, they could devastate the competition in the same way a computer program could dominate a chess tournament. And the better the camera and equipment, the better the result, which adds to the lack of fairness since people with less money and tools would be left out. Of course, you could point out the irony of banning ‘computer generated art‘ when every single image on Reddit is generated by a computer reading code and displaying a colour on a screen, but I have something more important in mind.

Namely, the way in which this is a remix of the Ugly Duckling Aesthetic Philosophy—sure, a work may be hideous and meaningless, but the important thing is that the artist tried, they suffered, and they deserve to be accepted and loved for the effort, not the result of their work. Imagine it as a moral given to children—even if you did a bad job, it’s okay because you tried your best!

Participation trophies for all!

I’ve done a lot of experiments with style transfer software and a lot of them turn out like hideous garbage. My aim with Park Boys was to create beautiful, meaningful art that celebrates children, the human body, health, my family and my culture. I think this is a moderately successful image. The brushstrokes look natural and digest the photo into satisfying planes of punchy colour, evoking a playful vitality appropriate to youth and childhood. When this picture was taken, our parents were Romanian refugees living in Belgium, where access to affordable, nutritious food and consumer goods was like a utopian fantasy come true.

Our parents must have spent a small fortune to get access to a camera since they were working demanding low-wage jobs just to get by, and the small selection of photos that remain from that period of time have the aura of precious gemstones for me. Despite our homeland being progressively destroyed throughout the 20th century, we managed to escape to the West, to abundance, to a brighter future. Here, we three are symbols of a prosperous future—lovable and playful little Pavel, cheeky and creative little Andrei, and the precocious scientific genius Iancu. I think the most successful one so far is this other photo with my aunt pouring water for Pavel to drink:

If I spent hundreds of hours creating these exact image with oil paint on canvas, would that magically transform its meaning and beauty? Maybe a little bit—people would take my time commitment seriously and assume that the picture is worth looking at as a result. Attention is valuable and people want guarantees that it won’t be wasted, so the more someone sacrifices the more they figure it’s worth paying attention to—if an artist kills themselves for their art then they might become famous forever. But again, what is the goal of art? Are we focusing on effort or results? In other words, why would I spend all that time doing tedious work by hand when I can use faster tools to create more meaningful beauty that celebrates healthy bodies and healthy families?

Again, this makes me sound like a bully—your effort doesn’t matter, the result matters.

No more whining, Johnson, I want that TPS report on my desk Monday morning!

What about all the poor people who put in hundreds of hours on something that looks really ugly? Let them toil! Be free, degenerate mutants! Poison the world to your delight! Let the growing thorns of your hatred of life give us all a new strength to grow from precocious cygnets into beautiful swans!

After all, the source for my style transfer is some ugly abstract art which I used since it had highly detailed brushstrokes that give more crisp results. Degeneracy can be useful. The more we build immunity in the face of aesthetic diseases, the better. I’m not a fan of the Goebbels style of approaching degenerate art by burning and banning it.

Maybe it would be wiser to have a democratic process determine the content of public art, but it might also be wise to curb State funding for the arts entirely. A State should focus on the most important element of a nation which is its military—something that nurtures discipline, camaraderie and strength among its citizens. This might be required for the Greco-Roman probiotic; recall that ancient Athens had a force of 40,000 men despite only having a population of half a million. That would be like the United States having well over 20 million soldiers—it currently only has about half a million.

9. The Fight Against Degeneracy

What matters for healthy modern art is beauty and meaning—the result, not the amount of hours put in, or the tools used. Beauty and meaning come from the family instinct, and the corruption of this instinct is what characterizes degeneracy. A child is meaning since a child is by its nature future-oriented—a child grows, it points beyond the limitations of present entropy. Caring for children requires personal sacrifice, empathy and patience, whereas modern life tends to treat child-rearing like a heavy burden that interferes with self-oriented pleasure-seeking. To focus on the effort of the individual is typical of degenerate art—I want credit for my effort, my expression, my struggle, even if the outcome is useless or ugly. Style transfer art floats in a weird grey zone—who’s responsible for the beauty? Is it the subjects of the photo? The manufacturers of the camera? The programmers who wrote the transfer code? The people who built the GPU? The person who painted the style source? All of them? None of them?

Hyper-individualism also perverts the most powerful physical experience of all. As Nordau puts it:

The instinct of propagating, which has lost its aim of reproducing the species, dies out in some persons and in others, degenerates into the strangest and most abnormal complications. The act of generation, that most sublime function of the organism, which can not take place until it has reached its full maturity and with which are connected the most powerful sensations of which the nervous system is capable, is degraded into a mere wanton sensuality no longer having for its object the preservation and reproduction of the species, but merely a gratification of the senses, without the slightest aim or value for the community.

Conventional Lies of our Civilization

Again, Hitler echoes Nordau’s sentiment in Mein Kampf, arguing that popular culture is corrupting people’s ideas of sex, and lamenting that syphilis is killing off young teens since they’re introduced to sex through prostitutes rather than the confines of marriage:

The fight against syphilis, and the prostitution that paves its way, is one of the gigantic tasks of humanity. It’s not merely a case of solving a single problem but the removal of a whole series of evils that are the contributory causes of this plague. Disease of the body in this case is merely the result of a sickening of the moral, social, and racial instincts.

[Source]

As Edward Dutton has pointed out, sexually transmitted infections are on the rise and certain diseases are developing more resistance to antibiotics—an urgent public health issue. This is to be expected with a culture that treats sex casually, rather than something sacred and principally oriented towards reproduction. And it’s easy to understand why that attitude is taken—raising children can ruin someone physically, emotionally and financially. A child may be a glowing gem of meaning, but meaning can be a heavy burden that crushes bone since all your decisions matter. Being a participant in the future of the human race is no small task.

Since children require constant guidance and education, there’s little room for ironic subversion, for being on the sidelines and taking potshots. Gazing into the horizon of the future requires the construction of sturdy scaffolding that prioritizes health, strength, sacrifice, and responsibility. Parents often get a lot of things wrong, and the consequences can be devastating for society at large.

A healthy child is a beautiful child, and since health isn’t really very subjective, neither is beauty—which means that there is an unforgiving hierarchy of health and beauty. There’s a reason that the bodies of men and women in the Great German Art Exhibit tended to be fit and young; a cohort study of more than a million subjects found that the more obese the mother, the greater the risk of severe congenital malformations, and hospitals warn about the marked increase in pregnancy complications for older women. It’s the same story for men—children of older men are more likely to have congenital heart disease, cancer, autism, premature birth, gestational diabetes, and so on. Paternal obesity is associated with all sorts of problems too. The ability to quickly recognize the health and beauty of people is a vital and necessary instinct—as Hughes said, anybody can understand a whacking great surfer with giant pecs holding up a sword! And as Dutton points out, a symmetrical face is a crucial feature of beauty, since symmetry means lower mutational load. A high mutational load, on the other hand, means an inability to fight off disease, which warps the body’s ability to maintain symmetry in the face of adversity.

Bodily training is more important than anything else, but it can be extremely difficult. Making good art is also a daunting task. Many will fail—and I continue to fail myself. I don’t have any kids, I’m not particularly fit, nor is my artwork the quality I wish it was. I might always be weaker, more self-absorbed and individualistic than I’d like to be, but the first step towards a healthy modern art is to aim in the right direction, to take the right probiotics so as to prevent aesthetic disease. We may still get sick and die, despite our precautions. Scratch that—we will all get sick, grow old and die. But we disciples of the Greco-Roman spirit will use the alkaloids from these bitter facts to fortify our aesthetic probiotics.