I’ve been reflecting on what separates me from the younger generation and it centers on our respective relationship to pain.

Kids have intense emotional outbursts which would derail my day if I were to experience as an adult; my nervous system doesn’t bounce back so quickly, nor do the consequences disappear so conveniently.

Whereas kids fight each other with vicious fury one moment, and play with delighted abandon the next. Their emotional troughs and peaks are more compressed—more volatile.

Yet they are also more stable since they recover quickly from illness and don’t have much responsibility. If a kid gets sick, it’s like a holiday—relaxing in bed or on a couch, watching cartoons, drinking soup.

When an adult gets sick, even mildly, it has a cascading effect on their long-term goals, their job, their obligations to their family and friends, and their self image.

The pain is analyzed, tracked, resented, and planned around rather than simply experienced as a passing phenomenon—even the whiny complaint of a child is cathartic because it solicits more soothing behaviour from the parent.

Since their bodies are still robust, children don’t focus their attention on physical pain so much as social pain, which is often what overwhelms them.

Since kids rely so heavily on the care of other people, their nervous system is sensitively wired to the reaction & acceptance of others, so much so that their body becomes the social world—exclusion feels like a physical attack and the threat of death.

That’s why their classroom drama has the salience of a catastrophic world-historical event—a friend’s betrayal might as well be the sack of Rome.

This total investment in social belonging also explains why younger generations like to invent and repurpose words. It’s one of the few ways they can build a boundary between themselves and the older generation that’s in control; they’re marking their territory and defining the out-group. Anyone who misuses a term (or uses an old version) is humiliated as an inferior foreigner—you’re not one of us, and you don’t matter.

But they’re also mirroring the way adults treat them—as incompetent, entitled, arrogant burdens. Adults feel they matter more because they have suffered and sacrificed more—especially for the kids—hence the trope about walking to school in the snow uphill every day for 10 miles. It’s a claim to legitimacy through pain.

When the old warn the young about the real world, they’re thinking of indefinitely being treated without mercy.

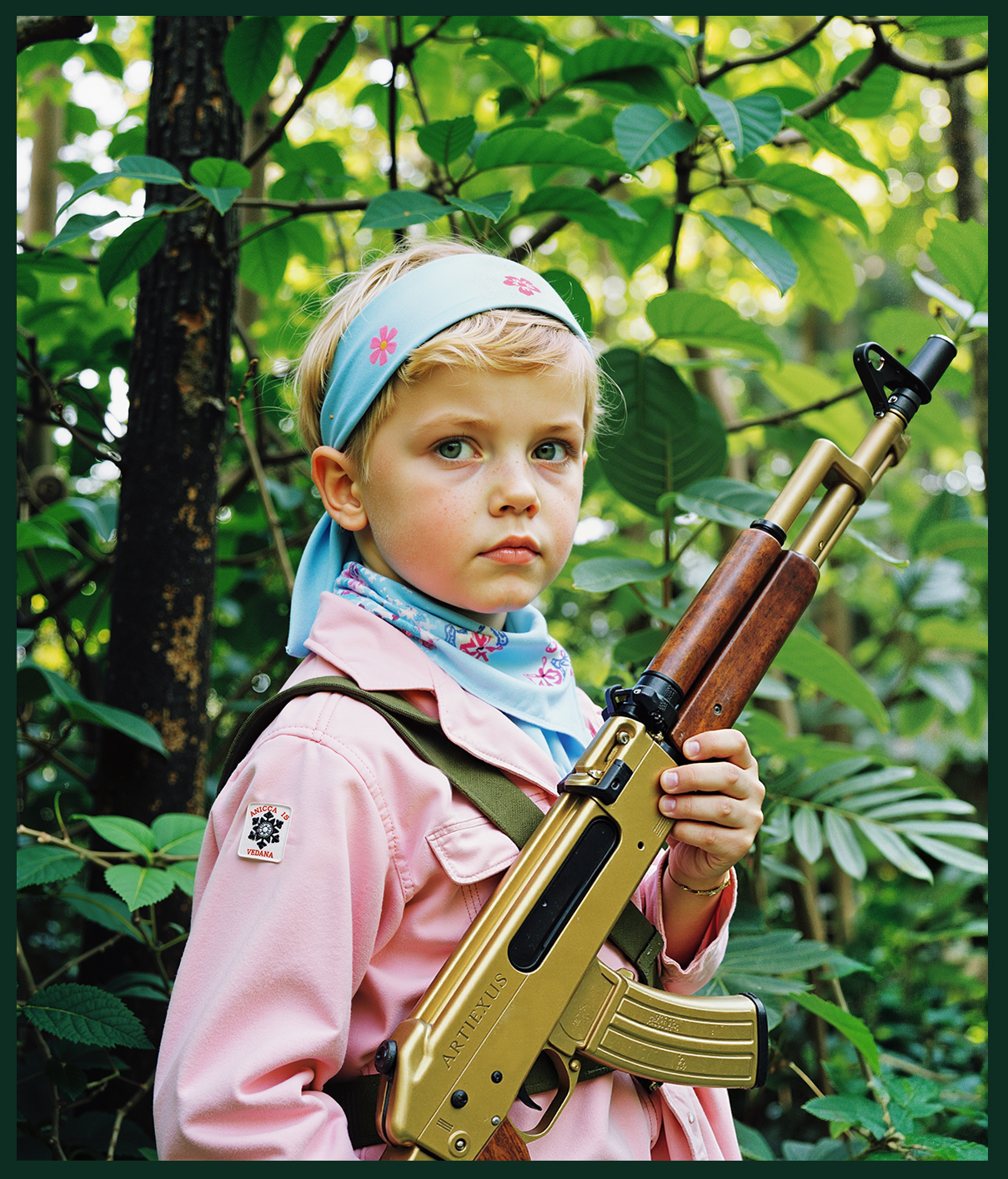

This is in contrast with the fake world of the child, which shields them from brutality. But they’re slowly introduced to it through school—which is primarily for learning to submit to authority and endure humiliation, hardship and competition.

In time, adults internalize this system so deeply that they mistake it for nature itself. That’s why political idealism feels so naïve to them; as one man in his late sixties told me, “if you’re young and you’re not a socialist, you have no heart, but if you’re old and you’re still a socialist, you have no brain“. Politics aside, the implication is clear; youth dreams while age braces for impact.

This disillusionment also changes the way the generations talk about parenthood.

Even though the social world diminishes with age, that isn’t necessarily a pleasant thing—it can mean becoming more invisible to others while the body screams for mercy that won’t come. And as the social dimension crumbles, so does the body—promising a clash with the unpleasant idea that everything valuable is disappearing.

A grandchild won’t replicate the grandparent directly, but they carry traces, like a brow, a smile or a temperament. That sweet or even nagging parental yearning for grandkids is a symptom of a deeper pain: I matter and I will continue to matter.

It also reinvigorates the social world, since being a grandparent earns more respect from others compared to just being an old person.

For young people, the question of kids doesn’t much matter, since it seems like an insane burden to take on. Young people have children as a consequence of their lust, as a form of self-aggrandizement, as a feeling of expansion, as fear of being excluded from their child-bearing peers, from the fear of being abandoned by their spouse who wants kids, from a vague urge, from broader cultural conditioning, as an obligation to their parents or their lineage, or boredom—but rarely because of a confrontation with their own mortality.

The real world earns its name because true understanding of pain can only accumulate over time—it can’t be imagined, only experienced. That’s the adult’s advantage over the child.

But the cost is steep; ‘reality‘ becomes so overwhelming that nothing else seems possible. The mind becomes ossified, rigid, defensive: How could you go against reality?