Abstract

I wrote this essay as a critique of common ideas about free markets and socialism, as found in an article by Carmen Alexe. I begin with the claim that that markets and governments are opposing forces by going through the origins of the market economy, with emphasis on the Mesopotamian credit system and the emergence of coinage in ancient Greece. Then, I analyze the idea that capitalism thrives without government interference, by looking at the role of capital in the colonization of the Americas, followed by a description of the Dutch East India Company and the beginning of the modern stock market. I also briefly touch on American foreign policy and its role in economic growth, followed by a case study in free market ideology. Finally, I analyze Christianity’s role in socialist thought and offer a detailed account of Romania’s political and economic struggles.

Market Makers

On State Power and Market Economies

In her Foundation for Economic Education article, Carmen Alexe introduces the Western reader to Romania’s history, briefly outlining how communism made the country crumble and explaining why free-market capitalism is the only way to freedom and prosperity. Living through the painful austerities of Romania in the ’80s and winding up in the material abundance of America should make anybody jump for joy, but Carmen goes further and makes lot of theoretical and historical claims that are worth examining.

Her main idea is a very familiar one: that markets without governments take the form of spontaneous business transactions which benefit everyone involved. While it’s a nice idea, we can look at historical records to see how it actually went down, and it turns out that markets were deliberate creations by states and based on coercive force. This is especially difficult to conceptualize when there’s an insistence that markets and states are opposing forces, with the former being a natural outgrowth of human communities, while the latter is either parasitic or oppressive. It’s appealing to imagine a Flinstones-like community with bakers and butchers buying and selling things peacefully, only to later have the government’s iron fist smash its unlucky victims. While there’s some truth to this, even scholars who are sympathetic to the autonomous market model like Stephan Epstein can’t help remark that ‘state formation was […] perhaps the major driving force of market integration and Smithian growth before the nineteenth century‘.

However, since Epstein was writing about Medieval Europe, it helps to go back a little further to get an idea of how market economies developed. Even farther back than coinage (since coins aren’t identical to money), all the way back to credit systems in place over five thousand years ago in ancient Mesopotamia.

The ancient Mesopotamian credit system was based on shekels and designed to ration stuff out for people who worked for the central governing body, basically a huge temple. Shekels were accounting units used to distribute goods and services collected through levying taxes and rents, although they didn’t require a physical equivalent, much in the same way that most modern money is stored as numbers in databases. This was a complicated task, and the main reasons that the Sumerians invented writing was to keep track of all the people and things that were being bought and sold.

Claude Levy-Strauss was only a little hyperbolic when he wrote that ‘the primary function of writing as a means of communication is to facilitate the enslavement of other human beings‘, since slaves were indeed an essential component of the goods and services used by the state to provision itself. Since money was an abstract tool, it would be weird to say that there wasn’t enough of it; the government’s demands for goods and services was only limited by how violently the population reacted. Plus, because there was no permanent army, rulers had to occasionally wipe the debt slate clean to prevent uprisings, which they could easily do since money and credit are abstract creations by people running the show, just as trillions of dollars were added to databases during the bank bailout of 2008. Note that ‘the market’ and ‘the state’ are essentially identical here, since ‘the market’ is a state appendage to provision the elite with goods.

This also explains why it took so long for coinage to become an economic phenomenon after coins were first minted in the 7th century B.C., although there wasn’t much of a distinction between economics and politics at that time. Since there wasn’t any stable authority around, rich families looking for political power would stamp precious metal as tokens for their followers with the personal seal of the family. Aside from flaunting wealth, this would reinforce their social status as generous and sophisticated. Such coins would have been circulated not as we would use coins (i.e., representing an abstract unit of value) but as part of the traditional system of gift-exchange, which carried with it a rich density of sociopolitical meaning. Almost everyone produced what they needed for their family and friends, so they had no need for anything like a market as we think of it.

Since plunder was seen as a normal way to acquire wealth, Athenians were keen to expand their military power in order to raid the world get more goodies. However, they were faced with a similar problem as rulers in ancient Mesopotamia where there was no permanent army. The rulers could only demand so much from their subjects until they faced resistance, and citizen-soldiers could only fight for short stretches since they had to return home and take part in subsistence activities like farming. Battles were quick, intense and decisive; the max range of armies was a 3-day march. However, Thucydides, an Athenian general and historian, pointed out that the key to success of Athenian political power was its navy, which required tons of public spending. Pericles, right before the start of the Peloponnesian War, suggested that the entire wealth of the city-state was necessary to win the war. This required a shift from using coins as a political tool to flaunt wealth into a practical economic tool for military power and conquest.

By paying soldiers in coins and making it so that peasants had to pay taxes in coins, the bulk of the city-state’s productive labourers would be forced to become little businessmen by providing a permanent supply of goods to the market. This not only allowed the establishment of a permanent naval fleet but also an incredible growth of military power that bloomed after every war. It was important that the Athenian state owned the mines in Laurion (some 40 miles away from Athens) in order to prevent people having access to the means of making their own coins and gaming the system, although it should be noted that working in the mines was notoriously hellish, involving ten-hour shifts around the clock in three-foot tunnels. The only reason people could be convinced to work there was by enslaving them, either through wars or debt peonage. Although the mine was state-controlled, it was leased to private citizens who became fabulously rich.

With coinage and the boom of military power and the market, slaves would be busy mining metal for the very coins which perpetuated their powerlessness. Given that bigger armies could loot and enslave more with each conquest, this style of subjugation enjoyed spectacular growth, reaching dizzying heights in the Roman Empire.

The market is therefore far from a neutral tool arising out of spontaneous transactions, but rather a political creation by rulers to wield power over their subjects and win wars. A clear example of this is when the Athenians invaded the Melians and offered them two options: pay up or die. The Melians chose defiance, and as a result, every adult male was executed, while Melian women and children were sold into slavery. Thucydides summarizes this realpolitik philosophy as follows:

The strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.

Given Max Weber’s definition of a state as a ‘human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory‘, it should be expected that societal elements like a market would be an appendage of the group which is given the right to exercise this force.

After the collapse of the Roman Empire and the dissolution of their gigantic army, most Europeans could finally enjoy a slight reprieve from constant slavery and violence. When the Frankish king Chilperic I tried to shake down his subjects for cash in the late 6th century, the citizens burned all the tax files and forced him to promise never to collect taxes again. However, by the 11th century we can see markets re-emerging to provide support for projects like the invasion of England, and new mining operations led to coinage making a comeback in the 12th century. Thereafter, Europe is graced with an increasing arms race that comprises the violently spilled blood of millions.

The old coinage trick has been used many times over by states to expand their power and wealth. When the British invaded Africa, for example, the way they sometimes forced people to grow cash crops like coffee (instead of real food for themselves) was to impose a ‘Hut Tax’, payable only in shillings. Unless the indigenous population shifted production to coffee and ‘sold‘ it to Brits for those shillings, their huts would be burned to the ground. They hustled to get coffee beans on the market not because it was a wonderful employment opportunity, but because they didn’t want their lives to be destroyed any further.

Lil Cappy

Early Capitalism and Colonialism

So how does capitalism fit into this? Alexe defines capitalism as follows:

The layman definition of capitalism is the economic system in which people and businesses engage in manufacturing, trading, and exchanging products and services without government interference.

However, there’s a problem here. Capitalism is not identical to the production and exchange of goods, since that would place its origin in the Stone Age millions of years ago, but it’s rather one of many modes of production. It relies on capitalization of assets (hence the name), which basically means turning things and people into money. Alexe’s insistence that pure capitalism is divorced from government interference also has a problem in that it bears no resemblance to the history of capitalism or its contemporary instantiations. Although we could start with prototypical companies like the publicani in the Roman Empire, a more useful example would be the Spanish colonization of the Americas, since it takes place at a time when institutions were using explicit profit-seeking logic in their bookkeeping.

In the early 15th century, the top merchants in Venice and Genoa transformed the money they made in the luxury goods trade into banks, which bought so much political influence that they took control of their city-states; the bank’s board of directors was identical with the government. They became the richest cities in Europe, lending to kings and popes alike for their wars.

Their hunger for precious metals provided the single-minded motivation to plunder the newly discovered American territory as quickly and exhaustively as possible. The soldiers who went overseas were in debt to their commanders, who were in debt to the crown, which was in debt to merchant city-states like Genoa (where Cristopher Columbus was from), which also had debts to China. Since the banks were run by the same people who had control of huge armies, you better believe those debts had to be paid, and with chunky rates of interest. When Columbus sailed the ocean blue and hit Hispaniola, he kidnapped 500 people (of which 200 died on the trip) to have something to show his investors. In order to get financing for a second trip, he promised the bankers ‘as much gold and as many slaves as you like‘, which meant going from hustle mode to beast mode in order to give a healthy ROI on the capital investment.

This involved the implementation of gold quotas in Hispaniola, forcing every man over the age of 14 to scour the island for the precious metal, and if quotas were not met, they’d get their hands cut off and be left for dead. Since there wasn’t really any gold on the island, the indigenous Arawaks ran for their lives. Columbus and his crew were furious and began hunting them down to burn them alive or hang them, which in turn inspired the Arawaks to commit suicide en masse. The Arawaks even slaughtered their own children to avoid the greater horror of having them fall into Spanish hands. In just a couple of years, about half of the population was wiped out, roughly 125,000 people. After forcing the survivors to become plantation slaves, nearly all the rest died, with only about 500 remaining.

Although capitalization of their assets didn’t go quite as they hoped, there was plenty more to be found in South and Central America. Since the indigenous people were seen as expendable tools to maximize profit, millions were directly murdered or literally worked to death in grim conditions, while tens of millions more were wiped out through disease (which was exacerbated by being jammed inside the Earth). Their behaviour was documented by a Spanish priest:

They laid wagers on whether they could manage to slice a man in two at a stroke, or cut an individual’s head from his body, or disembowel him with a single blow of their axes. They grabbed suckling infants by the feet and, ripping them from their mothers’ breasts, dashed them headlong against the rocks. Others, laughing and joking all the while, threw them over their shoulders into a river.

They spared no one, erecting especially wide gibbets on which they could string their victims up with their feet just off the ground and then burn them alive thirteen at a time, in honour of our Saviour and the twelve Apostles, or tie dry straw to their bodies and set fire to it. Some they chose to keep alive and simply cut their wrists, leaving their hands dangling, saying to them: ‘Take this letter’—meaning that their sorry condition would act as a warning to those hiding in the hills.

One of the reasons they acted like this is because Spain had been through several generations of war, and thus were raised in crooked ways; the Spanish were shocked that indigenous American parents didn’t beat their children. But their overriding principle was profit, which doesn’t care about methods, just about a number going up, and their project was identical with the state who backed their right to use lethal force. And similar to Hispaniola, once they killed just about everyone, they began to import African slaves. Presumably all the profits had something to do with the Renaissance; after all, Leonardo da Vinci designed a robot knight for Ludovico Sforza, who was both a warlord and a duke.

Big Cappy

State Power and the Modern Stock Market

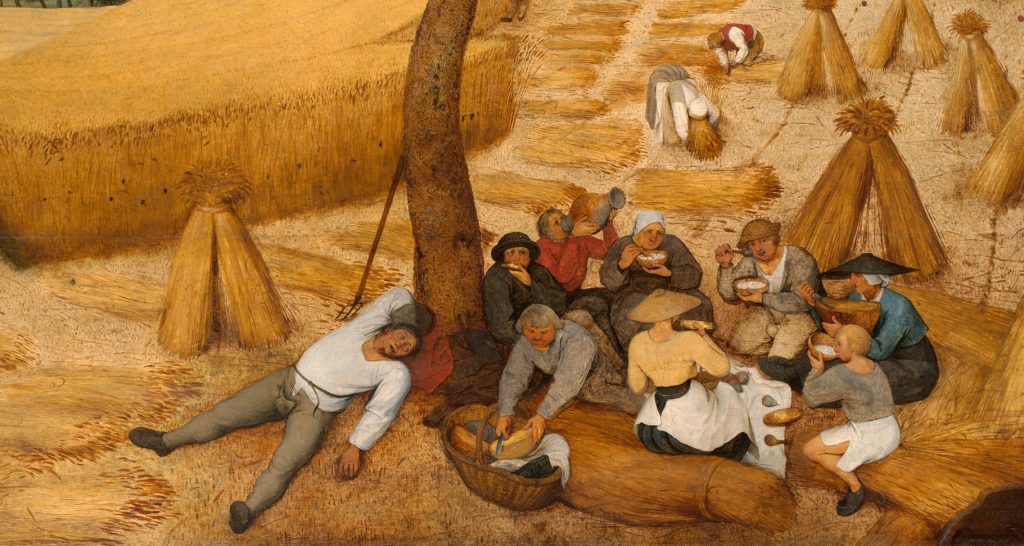

When it comes to the start of more modern capitalism, our prime example is the Dutch East India Company founded in 1602. Although the first merchants who found the legendary Spice Islands in Indonesia made enormous sums of money, competition meant that profits were steadily falling. They figured if they could create a cartel backed by the state, they could conceivably rule the spice trade by dint of monopoly. The DEIC, which boasted mercenaries with sworn allegiance to the company, was the first publicly traded company on the first stock exchange, providing the model for today’s stock market. Their entire goal was to make profits, and the shareholders only cared if the numbers went up. The distinctly amoral nature of this project had the consequences you might expect.

In 1621, the DEIC killed almost every single person they found on the Banda Islands and enslaved the remaining few. When they got home and sold the loot, they made tons of money, and Amsterdam eventually became the wealthiest city in Europe. It must have seemed like the greatest economic system to date since people got the goodies they wanted, the DEIC got funds for more trips, and the whole city became more prosperous. Surely, Dutch citizens would have simply pointed to the wealth and freedom that the corporation brought to their country; why should anything change? And indeed, there was a great cultural renaissance and internationally renowned tolerance funded by the spoils. The murder that underpinned it was easy enough to sweep under the rug, not to mention the slavery, which was impressively cruel; so bad, in fact, that slaves had to be shipped in from elsewhere as the indigenous ones kept dying.

Carnage and slavery wasn’t a boutique sector of Western economies, but arguably their core. This was unabashedly laid out by pro-slavery lobbies in the late 18th century:

The most approved Judges of the Commercial Interests of these Kingdoms have been of the opinion that our West-Indian and African Trades are the most nationally beneficial of any we carry on…

That Traffic alone affords our Planters a constant supply of Negro Servants for the Culture of their Lands in the produce of Sugars, Tobacco, Rice, Rum, Cotton, Fustick, Pimento and all our other Plantation Produce: so that the extensive Employment of our other Shipping in, to and from America, the great Brood of Seamen consequent thereupon, and the daily bread of the most considerable of our British Manufactures, are owing primarily to the Labour of Negroes.

As in Renaissance Italy, business interests in the African slave trade were effectively identical with the state; William Beckford, who owned a 22,000 acre estate in Jamaica, was twice the Lord Mayor of London.

It’s hard to imagine just how rough the African slave trade was; about 20 million were kidnapped and forced on long marches to the coasts, which killed half of them. Then another quarter died on the voyage, as they were put in chains and crammed in quarters so tight that they could not even turn over as they lay down. The ones that survived the voyage and tried to escape would get their ears cut off, their hamstrings severed, or were simply executed. They would also be forcibly separated from slaves who shared the same language so that they couldn’t hatch up any plans for escape or rebellion. Although increased social activism and slave revolts eventually made it less acceptable to enslave people for profit, the forces that instigated it have been more difficult to keep at bay.

Star Spangled Angle

American Foreign Policy and Military Power

Smedley Butler, the most decorated Marine in United States history at the time of his death, learned the hard way that military force is essentially a venture for the ruling class to enrich themselves, not a beacon of peace for a troubled world. He expressed this in no uncertain terms:

I spent 33 years and four months in active military service and during that period I spent most of my time as a high class muscle man for Big Business, for Wall Street and the bankers. In short, I was a racketeer, a gangster for capitalism. I helped make Mexico and especially Tampico safe for American oil interests in 1914. I helped make Haiti and Cuba a decent place for the National City Bank boys to collect revenues in. I helped in the raping of half a dozen Central American republics for the benefit of Wall Street.

I helped purify Nicaragua for the International Banking House of Brown Brothers in 1902-1912. I brought light to the Dominican Republic for the American sugar interests in 1916. I helped make Honduras right for the American fruit companies in 1903. In China in 1927 I helped see to it that Standard Oil went on its way unmolested. Looking back on it, I might have given Al Capone a few hints. The best he could do was to operate his racket in three districts. I operated on three continents.

It’s not as if this stopped in the early 20th century. While Romania was busy starting its doomed social experiment, John Stockwell, a CIA whistleblower, estimated that at least six million people were killed by the United States in covert CIA operations between 1947 and 1987. In keeping with the DEIC model some 400 years before, murderous plunder abroad translates to fabulous wealth and peace at home.

Unlike the crude tyranny in Romania, however, America is much more cunning in its pursuit of power and wealth. For example, they provided $6 billion in cash to the Afghani Mujahadin in their war against the Soviets, a conflict which resulted in 2 million civilian deaths and 5 million refugees. The Soviets got their ass handed to them, thanks in no small part to the funding, but the blood wasn’t technically on Yankee hands. This is a remarkably intelligent way to avoid casualties of U.S. citizens and bad press while weakening an enemy.

Indeed, the American government was very busy during the ’80s building their empire. For example, they funded and trained Battalion 3-16 in Honduras, which abducted, tortured and assassinated leftist activists. U.S. agents gave President Jose Napoleon Duarte the biggest air force in Central America, and he used it to drop 3000 tons of (U.S.) bombs on civilians in El Salvador, creating a crisis that produced 500,000 internal refugees and inspired 750,000 to flee the country.

They gave money and weapons to Hissène Habré, who wound up being convicted of the death of some 40,000 people, and his secret police tortured their victims in unique ways like shoving their mouths around the running exhaust pipes of cars, all the while U.S. officials chose to turn a blind eye. My favourite example, though, is the Iran-Iraq war, a conflict with half a million deaths, where the U.S. supplied weapons to both sides.

My point in bringing these up is not to slander America or to moralize (especially since many of my favourite things in the world are American), but rather to underline the fact that ruthless military domination and expansion is integral in the shaping of the American economy. I don’t think it’s the case that these sorts of actions are resulting from anything as abstract as evil, but rather the overflowing will to power exemplified in the Athenian ultimatum to the Melians: give us what we want or we’re going to kill you.

Traditional Values

Caste Study of Free-Market Ideology

Alexe concedes that America is not a purely capitalist country, that its real glory lies in the 19th century when the state didn’t meddle in the market:

[…] I wish to clarify that the U.S. is not a truly free-market capitalist system. We still maintain stronger capitalist traits than most, however a few other nations who lead the way in economic freedom have surpassed us. The economic policy of the 19th Century with limited regulations and minimal taxation attracted the needed capital to our country.

To be charitable, I’ll assume she doesn’t want to go any farther back than 1865 and advocate for the right to own slaves, although it wouldn’t be inconsistent with her allergy to government intervening in private business; after all, enslaving people helps cut costs.

But there’s an excellent example of people in the 19th century consciously fighting government interference to allow a purely free market to operate, albeit not in America. When a drought hit India during British colonial rule in the late 19th century, the country was already transformed by the market system described earlier; Indian peasants were subjected to a tax which forced them to hand over produce to the British, under threat of violence, while also being obligated to grow cash crops like cotton or opium. When rain started to disappear because of El Niño, the peasants pleaded with their colonial rulers for some kind of famine relief.

However, Viceroy Lord Lytton argued that this would be interfering with the free market (ostensibly the best way to allocate resources), and the House of Commons agreed that they’re running a business in India, not a charity. And besides, said Sir Evelyn Baring, ‘every benevolent attempt to mitigate the effects of famine and defective sanitation serves but to enhance the evils resulting from overpopulation’. Large stores of grain were guarded by the military just like in the Chinese famine in the 20th century, while 320,000 tons of wheat was exported to Europe and sold at record prices.

About 10-30 million people died slow, painful deaths and watched their loved ones wither away, and there are plenty of photos available for those who need nightmare fuel. The people who still had some energy left made their way to British labour camps, where they were given food in exchange for physically demanding work, earning the food which had been stolen from them, but over 90% of these camp workers died. On top of all this, British colonial powers doubled their efforts to collect taxes during the famine in order to fund their invasion of Afghanistan.

At this point it might not be a surprise to mention that making profits for the British East India Company was the primary motivation of the violent subjugation of India. But trying to discipline people by starving them was not just applied to subjects of the British Raj. Back home in England, after people were forcibly booted off their farmland and compelled to work in factories or mines under threat of violence, the state passed laws offering basic support to avoid rebellions. Prominent doctors like Joseph Townsend railed against these new Poor Laws, arguing that letting people starve will increase their willingness to work and requires less effort than direct threat:

Hunger will tame the fiercest animals, it will teach decency and civility, obedience and subjugation. It is only hunger which can spur and goad them on to labor. Yet our laws have said, they shall never hunger. The laws, it must be confessed, have likewise said that they shall be compelled to work.

But then legal constraint is attended with too much trouble, violence, and noise; creates ill will, and never can be productive of good and acceptable service: whereas hunger is not only a peaceable, silent, unremitted pressure, but is the most natural motive to industry and labor.

I mean he’s not wrong, but I wonder: can we do better?

Red Dawn

Socialism and Christian Thought

One of the most striking ancestors of the famous communist line, from each according to their ability, to each according to their needs, can be found in the Acts of the Apostles, written in the late first century by a Greek physician named Luke:

All the believers were one in heart and mind. No one claimed that any of his possessions was his own, but they shared everything they had. With great power the apostles continued to testify to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus, and much grace was upon them all. There were no needy persons among them. For from time to time those who owned lands or houses sold them, brought the money from the sales and put it at the apostles’ feet, and it was distributed to anyone as he had need.

Notice that this turns the whole world upside down; instead of coinage being used to generate war, it’s a pool of resources for the needy, and instead of land ownership being a method of enslavement of the many to the few, it’s a source of wealth for all. Such a fantasy was the inverse of reality in the Roman Empire, one of the most impressive displays of the will to power ever witnessed.

As in Ancient Greece, most people were mere props for state support via coinage; the word soldier itself comes from a Latin root which literally refers to someone getting paid coins. Anyone who was found guilty of seditio (rebellion) or crimen maiestatis (insulting the emperor) was usually crucified, and this was not a rare event. During the First Jewish-Roman War, there were would be hundreds of people who would be crucified in a single day, with their corpses devoured by birds and dogs. The revolt in Judea ended with tens of thousands of Jews being executed, often by crucifixion, while Jerusalem was looted and destroyed. It was a clear message to people to know their place; the casualty counts of all the Jewish-Roman wars range into the millions, with plenty of people winding up as slaves.

Writers at the time, like Flavius Josephus, pointed out that there were many people who went around claiming divine guidance in their intent to change the tyrannical rule of the Empire. Some of them amassed thousands and were prepared to fight, while others fled to the forest, but they all shared a painful death at the hands of the state’s soldiers. The most familiar to us is the preacher from Nazareth who was seen as yet another Jewish rebel and prosecuted as such. St. Paul provocatively styled Jesus as the Son of God, the Redeemer who spoke the Good News or The Gospel, terms reserved for the Roman emperor, which eventually lead to Nero’s execution of Paul. Jesus was the inverted image of the emperor, advocating love of one’s enemies plus care of the sick and poor.

After nearly three centuries of incredible endurance, the community based on these teachings had a windfall with emperor Constantine, though in a pretty weird way. In 315, Constantine had a vision on a hilltop while he was looking at the sun, with a cross appearing and a block of text spelling out something like ‘by this you shall conquer‘. Later that night, he had a dream where Christ appeared to him, expounding on the cryptic remark and explaining that Constantine will have a military victory if he painted a stylized cross on his soldier’s shields.

As luck would have it this turned out to be true, in that Constantine’s soldiers managed to kill more people on the other side, and Constantine successfully managed to decapitate his brother-in-law in his quest for more political power. I’m not sure this is outlined by Christ in the Gospel, but this bloodshed was the most important turning point in the history of the religion, as it made Constantine a ‘Christian’, changing the cross from a symbol of selfless suffering into one of military might. In 385, this was made manifest with the first ever execution of a Christian bishop and his followers by fellow Christians, ostensibly for heretical things like meeting at villas instead of church, but in reality mostly to confiscate the condemned man’s sizeable wealth. Given the fact that Christianity had been officially sucked into the logic of violent top-down control, it’s to be expected that people used its name to justify all sorts of ugly things for centuries.

There were certain times when a more loving vision of the Gospel began to shyly rear its head again, such as in the German Peasants’ War in the 16th century. After Luther demanded that the Church stop corrupting the Christian religion by offering paid services to wipe out sin, other preachers took it a step further, advocating for a true return to the communism of the Gospels. They demanded that the property confiscated by the ruling class be returned to God and used for the benefit of all, and that the extortion routinely undertaken by landlords and agents of the state be put to an end. A massive uprising ended with soldiers killing about a hundred thousand people; roughly a third of the population. Luther sided with the authorities and called for the execution of all rebels, although he couldn’t help but remark on his cognitive dissonance:

Strange times, these, when a prince can win Heaven with bloodshed.

Strange Times

Socialism and Tyranny

But just as the message of peace is hammered home in the Gospels, the incessant discussion of freedom as a priority in socialist literature still inspires Alexe to write the following:

Personal freedom thrives in capitalism, declines in government-regulated economies, and vanishes in communism.

I personally doubt that the Arawak or the Banda Islanders would equate capitalism with freedom, but the implication here is a frequently expressed one: communism/socialism is synonymous with government, and it entails servitude to a central state bureaucracy run by elites. Certainly, one can be forgiven for believing this, given the gigantic and oppressive government running Romania in the 1980s. One thing to note, however, is that the grand boogeyman of communism, Karl Marx, railed against the ‘servile belief in the state‘, adding that the standing army, police, bureaucracy, clergy, and judicature exemplify the ‘purely repressive character‘ of state power. Writing about the Paris Commune, he explains that:

It was a Revolution against the State itself, of this supernaturalist abortion of society, a resumption by the people for the people of its own social life. It was not a revolution to transfer it from one faction of the ruling class to another, but a Revolution to break down this horrid machinery of class domination itself.

This hardly sounds like an advocate of Big Government. Indeed, if anything, Marx was too obsessed with conceiving of the most absolute freedom imaginable. But it was another matter entirely to break down this horrid machinery of class domination which had been stomping on people’s dreams of emancipation for millennia. Given Marx’s regrettable absence of a coherent social theory, it was unsurprising when Lenin botched the project of society’s reorganisation in State and Revolution. He couldn’t come up with anything much better than roving bands of macho men punishing the bad guys (i.e., capitalist parasites), a doomed revenge fantasy from the very start. However, such salient failures of socialist theory and praxis occludes the fact that there are many practical successes of socialist movements which are simply taken for granted, such as the eight-hour workday.

Take, for example, the Lowell Mill Girls in the 1830’s. They didn’t mince words:

When you sell your product, you retain your person. But when you sell your labor, you sell yourself, losing the rights of free men and becoming vassals of mammoth establishments of a monied aristocracy that threatens annihilation to anyone who questions their right to enslave and oppress.

Those who work in the mills ought to own them, not have the status of machines ruled by private despots who are entrenching monarchic principles on democratic soil as they drive downwards freedom and rights, civilization, health, morals and intellectuality in the new commercial feudalism.

Their work day started at 5:00 AM and finished at 7:00 PM, with an average of 73 hours a week. It was noisy, hot, and the air was dirty and tough to breathe. The workers lived in company-owned houses near the factory, which crammed over two dozen women into a single house, giving them a strict curfew along with a supervisor. It wouldn’t have been too much of a stretch to call them slaves. However, perhaps owing to the fact that they were together 24/7, there was a strong sense of camaraderie fostered among the workers. When the depression of the 1830’s hit and their wages dipped, they began to take action.

Their first strike didn’t quite work, but it started the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association, where the women elected their own officers, and held their own meetings, fairs, and parties. They started a petition for a 10-hour workday, initiating the first ever investigation into labour conditions by the government, although it didn’t do much, since the representative of Uncle Sam basically said: not our problem. They persisted and eventually managed to get the company to cut hours by 30 minutes, and the growing membership persuaded New Hampshire to pass a 10-hour workday, although there wasn’t any enforcement of it. After about eight years of political pressure, the Lowell corporations finally cut the workday down to 11 hours.

It took a couple more decades for the legislature in Illinois to pass an eight-hour workday, although there were lots of loopholes that made it useless. There was a citywide strike in Chicago that shut down the city, but it petered out after about a week. A year later, Congress passed an 8-hour day for federal employees, only to cut their wages by 20%. It took a few more decades and literally hundreds of thousands of people going on strike (plus plenty of arrests and some executions by the state) along with constant political pressure to finally get an 8-hour workday, which is still a distant dream for many people around the world.

In short, there was incalculable suffering that was expended for what seems like a modest accommodation that is now taken for granted. This is socialism; the work of coordinating communities of people and establishing a decent life for workers. Although there are lots of important figures, it’s largely the work of average and unknown people who have become largely invisible to history even though they often put their neck on the line for the benefit of others. So why was Romania such a failure?

The Romanian Empire

Exploring Romania’s Oppressive History

A Rough Start

Romanian history of the 20th century has some parallels to the Roman Empire in its gleeful use of state violence and oppression. As grain prices began to fall the early 1900s, the lessors of the land demanded more money from peasants, evicting anyone who couldn’t cough up the cash, which meant peasants would be out of work with no money, land or resources to feed themselves. This led to an uprising so massive that the ruling government had no idea what to do, so they resigned. But what could have been a new era of political power for the majority of Romanians ended swiftly, as the new government who took charge decided to teach them who’s boss; they ordered 140,000 soldiers to kill thousands of peasants and arrest thousands more. Of course, the actual landowners were never in any real danger from the peasants, just their administrative employees that were sent to the countryside to do the dirty work. But order was restored and the population was put in its place.

After the moral outrage that this massacre provoked, the new government offered some small concessions a while later to pat themselves on the back. But they made sure to tighten the grip on the population in a way that would prevent anything like the peasant revolt happening again. They formed The Directorate of Police and General Safety, a secret police organization whose entire goal was to crush any sort of political group that threatened the economic interests of the people running the show. They used both covert infiltration or outright violence, chucking people in prison if they demanded better wages or shorter workdays.

The secret police had their work cut out for them, especially in the early 1930s, since during that time Romania imposed severe austerity measures on the population (slashing some people’s salaries by up to 50%), inspiring people towards socialist theory which demanded freedom from such harsh conditions. Frustrations mounted, and there was a strike in 1933 where thousands of workers were demanding better compensation. Although the state’s forces were sent in to kill, there was some marked moral sensitivity; one of the soldiers who was ordered to open fire tried to convince his fellow soldiers that they’re on the wrong side of history, and was executed by another soldier for saying so. One of the men arrested in this strike was Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, who was sentenced to 12 years of hard labour in prison. He was transferred to an internment camp during WWII, which is where he met Nicolae Ceausescu. Dej would go on to become the first communist leader of Romania, with Ceausescu becoming his successor. Ceausescu, in fact, would be in charge of Romania during the time that Alexe writes about with justifiable bitterness.

Dej was quite a bit older than Ceausescu and must have been a powerful father figure, as he inspired Ceausescu to bully other communists in prison to fit Dej’s political ideas. Although they were in an internment camp, they ought to have considered themselves lucky. At the time, Romania was at war with the Soviet Union, and communists were seen as a liability to the war effort, but communism tended to be seen as a symptom of a greater disease, which was Judaism. When the wartime dictator Ion Antonescu (who was involved in the peasant massacre a few decades earlier) started his campaign against the so-called Judeo-Bolshevist threat, there wasn’t even the morsel of Nazi civility, opting instead to kill thousands of Jews on the street in broad daylight, later dumping their bodies in fields using train cars. Hundreds of thousands of non-combatants were eventually murdered, and Romania has the dubious distinction of being second only to Germany in its ethnic genocide during the war. The Roman Empire would have been proud.

Killing in the Name of…

Dej escaped prison in 1944, eventually finding himself in front of the King of Romania, forcing him to abdicate his throne at gunpoint, and wound up as the country’s ruler in 1948. However, Romania was a pawn in the greater scheme of things. During the meeting between Churchill and Stalin after the war ended, Romania was literally offered to Stalin on a piece of paper, and Stalin made sure to drain resources from them in the form of reparations.

Haiti, which is now synonymous with poverty, had a similar fate in the 19th century. Although slaves had actually won the war against their French captors, the French government made sure that war reparations and economic sanctions from their allies would crush any success the emancipated country had, a vindictive move which still haunts the country today. Stalin’s grip on Romania was strong in the 1950s. My grandma tells me that when she worked for the newspaper in Bucharest, there was a large portrait of Stalin hanging on the wall, and it was forbidden to laugh whenever one was in its presence.

Onwards & Upwards

Yet despite Stalin breathing down Dej’s neck, Romania went from one of the least developed countries in Europe at the start of the 20th century, to one of the fastest growing economies on the planet, doubling the GDP per capita. Soviet pressure to turn Romania in a supplier of food and material for other Soviet satellites was brushed off, and Dej began taking steps towards a society with abundant consumer goods, choosing to trade with with Western countries. It’s rumored that he was assassinated for this insubordination.

But even if the Romanian Communist Party was responsible for some newfound prosperity, it’s clear that little had changed in terms of its overall political structure. While they hit the reset button on the staff of the the secret police, its role was the same, with thousands of people arrested for challenging those in power. Not to mention that having a brutal upbringing and the power to enact revenge fantasies will simply not go well, no matter the political leaning. Indeed, after Dej’s death, Ceausescu was put in charge of the country, and eventually began to channel his inner ancient Egyptian monarch to take revenge for all the years of poverty, misery and abuse.

Perhaps inspired by how Nero initially ruled the Roman Empire with his mother, Ceausescu decided to make state rule a family affair. In 1973, he made his wife a member of the ruling Politburo, and in 1974 gave five members from his immediate family control of defense, internal affairs, planning, science, technology, and party cadres. He eliminated any political opposition and journalistic freedom, while ramping up the secret police to ancient Roman proportion in order to stomp out any disturbance from the working class. To complete the look of Roman Emperor, or perhaps Pharaoh, he ordered the construction of the world’s largest administrative building, slightly larger in volume than the Great Pyramid of Giza, which is still unfinished many decades later and lies mostly empty.

This tyrannical megalomania was blessed with that most malleable adjective—socialist—styling itself as the Socialist Republic of Romania. Keep in mind that the first concentration camps in Dachau, established in 1933 by the National Socialists, were ironically built to imprison communists, socialists and trade unionists, who were forced to wear red triangles which marked them as political threats. Below are some examples from an Amnesty International report that illustrates Ceausescu’s solidarity with the common man in the 1980s, eerily reminiscent of crimen maiestatis :

- A 56-year-old building worker makes a speech and distributes leaflets criticizing President Ceausescu—he is sentenced to nine years imprisonment for “propaganda against the socialist state”

- A teacher complains to a foreign radio station that he was unfairly dismissed from his job—he later dies in prison while serving an eight-year sentence for “disparaging the central organs of the party and the state”

- A 50-year-old electrician is arrested after driving through the center of Bucharest displaying a picture of President Ceausescu and the words “Nu te vrem calaule” (We don’t want you, hangman)—he is sentenced to 10 years’ imprisonment

- A father is denied permission to take his epileptic seven-year-old son abroad for medical treatment—and receives an eight-month jail sentence for trying to do so illegally

- A 28-year-old Baptist is reportedly tortured to force him to reveal the source of religious literature found in his home

- a 30-year-old teacher is imprisoned for “parasitism” after being refused employment because of his political views

The Short Straw

The Role of Socialism in Economic Collapse

Alexe claims that the brutal food shortages endured by Romania’s population during the 1980s were a direct result of the failure of socialism as an economic system. However, this explanation doesn’t seem to hold water, given that the same thing happened to many different countries at the same time, even though they were sometimes explicitly anti-communist.

After petrochemical companies dumped tons of profits into Western banks thanks to rising oil prices, bankers began giving chunky loans to the most iron-fisted dictators around the world, knowing that they could count on them for oppressive measures to get their money back. Once the interest rates skyrocketed, they wanted to make absolutely sure that they could collect every penny, so they used global powers like the International Monetary Fund as an enforcer. The IMF used Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs), which meant cuts on minimum wages, an end to trade unions, cuts on healthcare and education, privatization of the public sector, and the ability of foreign corporations and banks to buy whatever they want. Basically, gutting out the world for the Western ruling class, or as Alexe calls it, increased economic freedom and less government intervention.

In Zaire during the early ’70s and mid-’80s, SAPs made the average income fall by 3.9% a year, eventually leading it to be 90% lower than it was before Mobutu Sese Seko took power. SAP cuts to healthcare and agriculture also lead to a death of 1/3 of all children under the age of 5. The reason this is important is that Mobutu was a staunch anti-communist and received help from both Belgium and America to assassinate his socialist political rival, Patrice Lumumba, so it would be hard to suggest that socialism crashed his country in a way identical to Romania. However, journalists like Blaine Harden pointed out that there were some people who did well in Mobutu’s Zaire, namely: Mobutu and about 80 people who were his close associates.

When Ferdinand Marcos in the Philippines declared martial law to extend his rule of the country indefinitely in 1972, the loans started coming in by the billions. He had no interest in communism or socialism and even partnered with U.S. firms to build useless vanity projects in his country, knowing that his subjugated population was gonna pay everything back. Given the draconian rule and horrible poverty that Marcos inflicted on his people, he was finally ousted in 1986, although the debts were all still outstanding on the people who had nothing to do with taking out the loan in the first place.

Then there’s Somoza in Nicaragua, Duvalier in Haiti, but suffice to say the story’s pretty much the same, involving the collaboration of global financial powers and dictators to exploit millions of people for cash. Forcing millions of citizens to undergo SAPs because some guy borrowed tons of money is like creditors forcing a debtor’s family and friends to starve while he lives in palatial comfort. It makes even less sense when we consider the fact that loans come with a risk, which is built in to the whole idea of interest payments. Thucydides would have been impressed at the sophisticated technological improvements made on the old dynamics of coercion.

But just as it didn’t matter to DEIC stockholders whether people in the Banda Islands were happy, enslaved or dead, it made little difference to the banks or the IMF if people were being starving to death by a tyrannical king. Basically, it’s not their problem. Romania’s story is pretty much the same; Ceausescu ran up a bunch of debt which really got out of hand after America blew up the interest rates in the early ’80s, at which point the IMF pounced on the weakened country in order to loot it via SAPs. Ceausescu was unique because he was able to squeeze Romanians so much that all the debts were actually paid in record time (my people are a hardy lot!), although ironically, his reign ended in his execution by a massive uprising right after the country was debt-free. Others like Duvalier were luckier, flying far away with the money when people turned against him.

Economic Freedom

The Material Interests Behind Free-Market Ideology

(1st or 2nd century AD copy of a lost Greek bronze original attributed to Leochares, c. 325 B.C.)

When Alexe mentions economic freedom, she also provides a link which ranks countries by economic freedom. The list is run by The Fraser Institute, which advocates for less government interference in corporate interest, yet has received billions of dollars of funding from oil companies. I should point out that the IMF estimates the fossil fuel industry gets about five trillion dollars a year in government subsidies, which would be perfectly in line with the historical love affair between states and markets. But The Fraser Institute isn’t asking to stop getting oil money; rather, the type of government interference they’re referring to is just less public accountability for corporate decisions.

Back in the late 1970s, the NDP government in British Columbia created the Agricultural Land Reserve in order to stop speculators hoarding it for future development. The biggest forestry company at the time, MacMillan Bloedel, wasn’t happy about this since they had bought a plot of land with the intent to develop it, and now their investment was bunk. That’s when they got the bright idea to fund a think-tank which advocated against democratic control of natural resources: hello, Fraser Institute!

The people who ran Alexe’s article, the Foundation for Economic Freedom, was started by a man named Leonard Read. After Read’s attempt at starting a grocery business failed, he decided to make a career out of telling everyone how great business is. Eventually, he wound up in the United States Chamber of Commerce, which receives hundreds of millions of dollars from billion-dollar companies like the cigarette hawkers at Philip Morris, and was explicitly built to limit the political influence of labour movements. In short, I think it’s wise to be circumspect in assessing the neutrality of The Fraser Institute or any such emphatic glorification of free-market ideology.

Final Thoughts

While I’m guessing the institutes promoting falsehoods about ‘socialism’ and ‘the free market’ are acting in bad faith, it’s not clear to me that Alexe is doing so. Her rhetoric about lessening the power of the government is probably not a cynical ploy to crush labour movements, all the while receiving cash from government-subsidized oil companies. Rather, I think she basically believes: government bad, markets good. Nevermind the fact that it always seems to be social programs that are bad rather than the military, police, prisons, courts, etc. However, as I’ve tried to show throughout this essay, this sort of dichotomy is incoherent given the abundant historical data that exists regarding the formation of markets and large-scale economic enterprises. Even on a more intuitive psychological level, it seems strange to me to suggest that people who wield incredible economic power on the market will somehow avoid turning that influence into political power, and vice versa. Is this a bad thing? I don’t think moralizing has much of an effect, since having a great deal of power is probably way more delightful than the feeling of being morally pure. But the very least we can try to do is understand what is actually happening and to admit the un-pretty side of whatever shiny coin is being presented to us. Let the snakes show their fangs and revel in their scales.

None of this is to say that what Alexe proposes is impossible; namely, an economic structure that is not run by elite cadres with coercive force, but instead by the people whose labour constitute the goods and services. There are many examples of cultures with starkly different economic structures than ours, some of them without anything we’d recognize as a top-down governmental institution, such as the Nuer in South Sudan. But it’s not clear to me that the solution is as simple as cranking up the dial on vague things like ‘the free market’ and impoverishing political imagination by dismissing anything associated with ‘socialism’ or collective action.

The idea that we can remove government from the picture, when it’s offered in good faith, is probably an attempt to remove politics from life and dissolve the frustrating and complex power struggles into a mechanistic exchange. As an introvert, I can definitely understand the appeal of this, since it allows an unprecedented level of detachment from my society and culture. The thing is, it treats human beings as instruments for personal gain, and nothing is owed other than the stipulated amount, which seems to me like it would foster the very things we find in the unsavory origins of markets: lethal violence, infinite greed, and brutal slavery. In short, a callous disregard for other people.

I don’t think that blaming capitalism and trying to overthrow it will somehow erase the corruption in people’s hearts, what Christ called sklerokardia, or hard-heartedness. But genocides committed in the name of socialism shouldn’t mean there’s no hope for getting a decent discount on insulin, and the genocides committed in the name of the free market shouldn’t compel us to give up buying kale at the farmer’s market. Indeed, the third-world debt crisis of the ’80s helped us see that opposing political postures can be functionally identical. I suggest we thank our lucky stars we’re under the wing of the fiercest predator, but we shouldn’t be surprised that those talons are drenched in blood.