Abstract

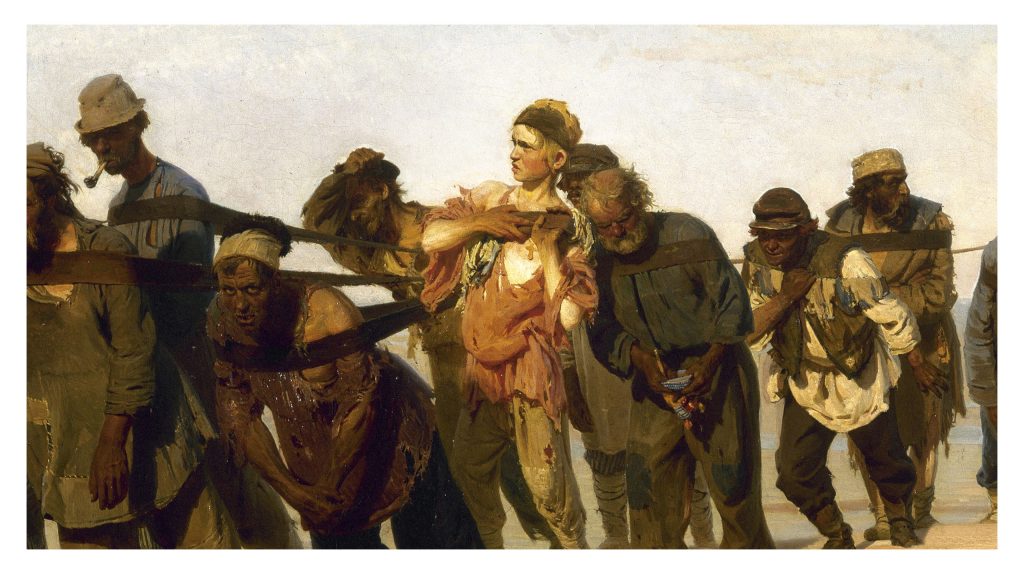

This essay is an answer to the question: can a ‘wageslave’ be happy? It begins with an introduction to the ‘antiwork’ movement and its corollary tensions in the thought of ancient Greece; the infamous Jesse Watters video interview is discussed alongside Aristophanes and his caricature of philosophers. After tying in Nietzsche’s reflections on work in The Greek State, there’s an extended analysis of Aristotle’s views on slavery, along with the perspective of former American slaves like Frederick Douglass and contemporary business magnates like Kevin O’Leary. Aristotle, Theognis and Socrates offer their perspective on the physiognomy of slaves, which are compared to contemporary examples of physiognomic discrimination. The work of Italian Renaissance artist Domenico Ghirlandaio is examined as a hopeful cultural icon, and Nietzsche’s concept of the ‘great spirit’ is introduced, with King Philip II offered as an example. The essay concludes with reflections on modern thinkers like Jordan Peterson and the role of Christianity in the modern worker’s life.

Chapters

- Introduction

- Dirty Work

- Natural Wageslaves

- The Body of a Wageslave

- The Anti-Christian Worker

- The Worker’s Future

1. Introduction

Have the upcoming decades of work ever felt like a dirty, cold flood?

Did these phantom waters seep into the basement of your soul?

Are they transforming your fondest dreams into bloated absurdities, far beyond repair?

Have the infinite stars of your mind become cloaked in the opaque grime of commercial labour?

Well, don’t say you weren’t warned.

Participating in a market economy would have been a contemptible thing in the ancient world, an activity reserved for an unfortunate section of the population who were sub-citizens. Selling one’s labour was, by Artistotle’s account, something that ‘degrades the mind‘. Two thousand years later, Adam Smith echoed this idea when he reflected on the division of labour, describing it as a process that makes people as ‘stupid and ignorant as it is possible for a human creature to become‘. Smith wasn’t hurling insults casually, but rather pointing out the logical consequences of making people ‘ensouled tools‘, to borrow Aristotle’s phrase. If someone specializes to perform a certain task for most of their waking hours, it’ll necessarily stunt various dimensions of their development.

It certainly feels like that for me. I’m lucky to have a white-collar job, but during the week, my mind still feels like it’s trapped in a dirty, dark haze, only receiving small gusts of fresh air and sunlight on the weekend that helps my mind grow just a smidge.

I know what you’re thinking: ‘yeah, you and everybody else, princess‘.

Wow, rude. But there’s some wisdom in this bitter pill, given that this is the global status quo except for a small minority of people. Most of us will, undoubtedly, spend most of our lives renting ourselves out to survive, and at least I wound up with a nice version of self-rental—I can work flexible hours from home. And after all, it’s honorable to work, isn’t it?

This was one of the central questions in a Jesse Watters video interview, where he talked to Doreen Ford—a representative of the ‘antiwork’ community on Reddit. Doreen was put into the unfortunate position of having to defend laziness in contrast to work, which made a bad image worse. Doreen—a part time dog walker who loves philosophy—had an unkempt appearance, skittish body language, ugly lighting, a humorless attitude and messy room—all of which stood in stark contrast to Jesse’s beautiful suit, clean studio lighting, professionally groomed hair, subtle makeup, and boisterous confidence and rhetorical skill. Stated somewhat hyperbolically, in that interview, Doreen’s interest in philosophy, compared to Jesse’s practical success in the world, represents some kind of illness, of a deterioration of life by becoming disconnected from beauty and strength.

This was already sketched out by Aristophanes in his play Νεφέλαι (Nephelai, Greek for The Clouds) from around 420 BC. In this story, there’s a guy named Strepsiades, and his son Pheidippides has been sucking the family wallet dry because of his gambling addiction. Strepsiades is drowning in debt as a result, so he tries to get his son in a place called The Thinkery where students are taught by some botched creature that having an easy life, shirking discipline, responsibility and practical success is a good thing—and with this in mind they learn to twist words to their advantage—their ‘philosophizing’—so they can defeat creditors in court. Aristophanes was poking fun at Socrates, probably the most important figures in its history.

And yet for people like Aristotle, who wrote his work almost a century later, it was obvious that the only way to real happiness was a life of leisure—maybe you engaged in the delight of philosophy and politics, but at the very least you cannot be happy while under someone else’s thumb. A happy worker was a contradiction in terms. Two thousand later, Nietzsche kind of agreed—more on that later—and declared that anyone whose day isn’t mostly free time is enslaved.

Nietzsche also claimed that nobody worth their salt would look at Hera in Argos and dream of being a Polykleitos; in other words, great people who see great art don’t care to waste their time with the hardship of production—they love to enjoy fruits in the shade, rather than labour in the hot sun. In fact, he goes on to claim that any worthwhile culture depends on the enslavement of labourers, and that it’s a cruel joke to have the idea of ‘dignity’ glued on to this kind of coerced labour.

Head of Hera by Polykleitos [Source]

2. Dirty Work

The dirty work required for survival was to be passed on to the masses who were unable to claw their way to the top of the leisure class of society by dint of their various degrees of unfreedom. Such a culture could be compared to ‘a blood-stained victor, who in his triumphal procession carries the defeated along as slaves chained to his chariot, slaves whom a beneficent power has so blinded that, almost crushed by the wheels of the chariot, they nevertheless still exclaim: “Dignity of labour!” Dignity of man!”

Yet it’s obscene to have a life of leisure while everyone else toils. I’m uncomfortable being served at a restaurant, since a precious human mind is being disrupted by mechanical activity rather than blooming in the direction of an obscured sun. I feel uneasy when I see cleaners mopping the same floor day after day, the light of their souls slowly dimming. According to Nietzsche, this would be an example of thinking which bubbled out of the slaves of society rather than its masters, what he called a slave morality: ‘it is disgraceful to be fortunate; there is too much misery“.

But what if such people love their jobs? What if they escaped from a country where earning money safely and having enough food on the table is a rare gift? Gratitude is an essential part of mental health, and I think it should be cultivated to the utmost degree. However, I can think of times where my lack of gratitude was motivation for developing myself in healthier directions. Nietzsche offers some compelling reasons to be mistrustful of moral sentiments which we take for granted, such as patience and humility, by looking at their historical development.

Let’s consider a more cynical perspective: what if these workers, dubbed wageslaves by detractors, maxed out their talents doing menial work? What if some people don’t have the brains or ambition for anything greater than floor-mopping? This sounds like Aristotle’s concept of natural slaves, which describes a type of person that’s best suited to become an instrument of a master who commands logos (reason, creative order). A slave can apprehend logos enough to follow orders, but they do not possess it as a creative force. It might be that Aristotle speculated about the possibility of natural slaves in order to cover up the ugly fact that things could be a lot more fair, and slaves lost their freedom through force and violence rather than intellectual ineptitude in a ranked cosmic order.

But his basic insight is common sense; some people are born leaders and others are more inclined to be agreeable and follow along. Take, for example, Kevin O’Leary—a Canadian businessman— and his ‘gum story’, which inspired him to become an entrepreneur. It goes something like this: he gets hired to work at an ice cream store, his boss asks him to scrape the gum off the floor, he finds it degrading, he refuses and gets fired, prompting his mom, Georgette, to give him some very straightforward advice: There’s two types of people in the world: those that own the store and those that scrape the shit off the floor, and you have to decide which one you are.

In other words, are you a slave or a master? O’Leary took the advice to heart and opted for the latter. However, as journalist Bruce Livesey has pointed out, O’Leary started a business and lied about its earnings to swallow other companies, got even bigger, cooked the books some more, then sold it off for a big chunk of cash while everybody else took a huge loss. The company that bought O’Leary’s lemon expected $50 million in profits only to lose over $100 million, wiping out $2 billion in stock value in a single day. O’Leary, however, cashed out with $11.2 million: mama would be proud!

3. Natural Wageslaves

Hopefully we can foster better masters than Kevin, but the point still remains; consider the question of life’s purpose, how clearly driven and confident some people are. Yet, for others it’s an urgent necessity to be an instrument of something or someone else—if only there were commands from a masterful source, a certainty that a brilliant logos awaits, pre-packaged and palatable like a sweet breakfast cereal. As Dostoevsky puts it via his character of the Grand Inquisitor: there is no more ceaseless or tormenting care for man, as long as he remains free, than to find someone to bow down to as soon as possible. Not a foreign feeling for me.

In contrast to Plato’s suggestion to punish slaves, Aristotle opts for admonition, believing that slaves are capable of some kind of understanding of logos, however imperfect. For example, in the Nicomachean Ethics, he sketches out a slave who is too blinded by his anger to pay proper attention to orders. This slave receives logos in an imperfect way, storming off before it’s appropriate to leave, doing a poor job as a result.

However, this imperfect attention to duty may have been a calculated means of asserting some form of resistance.

Black American slaves in the 19th century like Frederick Douglass have confirmed this, explaining that among slaves it was advantageous to dupe the master into assuming his slaves were ignorant—it gave them a secret form of power. Such malicious compliance is a tried and true tradition in America, as explained by Homer Simpson:

Lisa, if you don’t like your job, you don’t strike! You just go in every day and do it really half-assed. That’s the American way.

Season 6, Episode 21

Homer’s observation rings true, although I think this subtle vengeance is usually masked as a form of justice, or at least hiding in the safety of the crowd and saying—’everybody does it‘. What’s worse, though, is the common lurking desire among ostensibly kind and well-behaved people to dominate others. Douglass made the grim observation that ‘everybody, in the South, wants the privilege of whipping somebody else‘. That is to say, even within groups of people who were dehumanized tools, there was a fight to establish a pecking order—so that there was a chance at being at the top of rock-bottom.

Despite Aristotle’s focus on slaves as members of the oikos or household, it should be understood that slaves were involved in a wide variety of activities like agriculture and manufacturing, which means slavery was on a spectrum—it wasn’t necessarily a slow death sentence or a nightmare from beginning to end. Slaves who worked in mines lived horrible lives of near-total unfreedom, but public slaves like clerks would be much closer to living an independent life, paying rent to their distant masters and working a clean and relatively comfortable job.

This spectrum of slavery was echoed in the plantation system Douglass was familiar with. Even within the same household or enterprise, there was a hierarchy of slaves, which was encouraged by masters through offering special positions, separating the house slaves from those toiling in the field, and establishing hierarchies in both domains. Nicias, a politician in ancient Athens, owned about a thousand mine-slaves who he forced to work in three-foot tunnels for ten hours a day. However, he contracted out the ownership of these slaves to a non-Athenian slave, an overseer, whose slavery was much more comfortable.

Aristotle encouraged masters to delegate slave management to overseers since it was a waste of time for a free man. Removing slaves and slavery from daily life meant there was a smaller chance of cultivating pity and sympathy for people that clearly had a rough life.

Nonetheless, one of Aristotle’s followers, Theophrastus, remarked that it’s both righteous and useful to offer slaves the possibility of freedom. He thought masters ought to treat slaves in a managerial position with respect, offering them rewards, holidays, and even families, although their children were basically replacement slaves.

But Theophrastus also warned about the agroikos, something like a country bumpkin, a person who foolishly gets close to his slaves. An agroikos might answer the front door by himself, try to bang his sexy bread-baking slave, offer to help grind up grain, and engage slaves in conversation. Such behaviour is a clear example of an unnatural master for Theophrastus.

The only alternative to slavery, in Aristotle’s eyes, was magic. If fabrics could weave themselves, for example, what would be the point of having masters and slaves? But since no such magic existed, anybody who was free and had money would obviously just get someone else to slave away for them. It would have been bizarre to be a free person and make stuff for the market to get income, since this was a waste of time for a citizen. As Xenophon put it bluntly, ‘those who can afford it have slaves as co-workers‘; he even came up with something akin to a Universal Basic Income, where the state would provide for every citizen using the revenues from publicly owned slaves working in the mines.

Aristotle saw that the actual enslavement of other people resulted from an abundance of violent force, which he termed unnatural slavery. But how could it be that there was so much unnatural slavery—why was nature so confused? And more specifically, how could it be justified that Greece was perpetrating such a thing?

The answer was that anybody who wasn’t Greek was really a barbarian (something less than fully human) so you couldn’t expect them to be much more than slaves. There was a general understanding that the barbarian’s inferiority was reflected in its physical constitution, either in stark or subtle forms. Socrates claimed that free men in the gym had a different scent than slaves, whereas Theognis said that a slave’s head is ‘never upright, but always bent, and he has a slanting neck‘—this reminds me of the ‘virgin and chad’ memes which has a frail-looking wisp of a man with a slanted neck, and he’s the butt of the joke. Aesop, who wrote the famous fables, was originally a slave and became a famous Greek author—yet, since he was from the conquered barbarian population of Thrace, he’s described in some unfavourable terms: ‘pot bellied, weasel-armed, hunchbacked, a squalid, squinting, swarthy midget with crooked legs.’

4. The Body of a Wageslave

Using people’s physiology to justify their position in the social hierarchy has a long history and still plays an important role in the 21st century, sometimes in unexpected ways. In an episode of the Simpsons where Abe and Homer start a business together, Abe tries to think of something nice to say about Homer—who he had called an accident and a stupid screw-up. The best thing he can come up with is: ‘I was always proud you’re not a short man‘. Empirical studies which examine the link between intelligence and height found that bishops tend to be taller than preachers in small towns, sales managers are taller than salesmen, and white-collar workers are taller than blue-collar workers. In one study, they found a one-inch increase in height might boost weakly earnings by almost 3%. The overall correlation coefficient between intelligence and height is 0.2, which means it’s a very small effect, but it’s not nothing.

In internet memes, the intellectually inferior person in the joke is immediately clear if they’re rendered as ugly and deformed; the ‘retard wojak’ template features caricatures where people’s eyes are asymettrical, they have drool and snot pouring out of their orifices, bad teeth, misshapen heads, they’re inappropriately emotional—their bodies preclude a grasp of logos or its command— they’re a sort of natural slave.

This isn’t too far from reality; there are a couple of employees at my local grocery store who move carts around, and they struggle to perform these simple tasks with any grace, and they look like they have some kind of congenital deformations. Civility demands that such people be treated with the utmost kindness and respect; I once had a dream that I looked into a mirror and my face was unusually beautiful—all the things I hated about it were fixed and the results were spectacular; it’s so much nicer being really beautiful! And yet as I kept staring at the mirror, a series of cancerous growths started to spread in my left eye, pushing out my left eye and morphing the left side of my skull into a hideous blob—how could this happen to me? How could I stand to be a hideous monster for the rest of my life? Don’t I deserve love and respect like all human beings despite my unfortunate fate in life?

It’s a nice idea, and represented beautifully in paintings like Ritratto di vecchio con nipote (An Old Man and his Grandson) by Domenico Ghirlandaio from 1490. One thing I love about this painting is that it that the subjects are anonymous—it’s unknown who they are or whether or not they’re related. I think that’s part of Ghirlandaio’s point—the healthy young boy is the glowing hope, not just of his family but his nation and planet. And this boy honours and loves his ugly, imperfect predecessors, honors their tradition, making it stronger and sharper—Ghirlandaio was, after all, one of Michelangelo’s teachers. It reminds me of my grandfather, someone whose health was pretty shaky, but he always showed me his most gentle, loving side humanly possible, no matter what I did—once, when my parents were driving home from the airport, I was sitting with him in the back seat and I was so happy to see him that I hugged him and held on for as long as I could, effectively until my back started to scream in pain.

But these loving attitudes are rare and can’t really encompass all the rejects of society. All of my personal experience has taught me that there are many people who are above me, and they are treated and recognized as such by others, both for good reasons and bad. When I worked at a factory, I spoke with one of the machine operators who pulled twelve-hour shifts, doing loud and challenging labour. He was middle-aged and had resigned himself to performing this mindless duty, explaining that his performance in school had effectively doomed him to the lower caste of society—that’s life, he chuckled.

Wait, what?

I thought that everybody has the same dignity no matter their family background, their intelligence, their schooling? Well—someone has to do the dirty work, and just because two people banged and created a person, that might not translate into everyone on the planet scrambling to give that child the finest things in life. When I was a kid, I found it tough to understand why my parents bugged me so constantly about doing well in school. I kept thinking: I’m valuable, aren’t I? I thought all kids are valuable! The world will just recognize our value and things will be fine.

But they knew through difficult and painful experience as immigrants, through a scar left on their psyche, that the world will eat me alive if I don’t jump through the requisite hoops—burning hoops though they may be—and I’ll be lucky if I have a somewhat decent job being a so-called ‘wageslave’. This acceptance, however, comes at a cost, which is that the mind becomes dumb, it becomes corrupted by slavish thought—like an excessive tendency towards self-abasement and obedience. Nietzsche identified this as the Christian tendency; in other words, to be in a position of weakness, vulnerability, and pain—at the bottom—and then flip the world upside down so you come out on top. This is something like the flip described in The Thinkery—athleticism and responsible worldly success is ignored in favour of so-called ‘spiritual’ things. In small doses, this flip can be great—how else to appreciate the richness of the mind and its various sublimations? Foucault became a scholar by reading a lot to impress a cute guy he had a crush on.

5. The Anti-Christian Worker

In The Antichrist, Nietzsche describes the order of rank as a formula for ‘the supreme law of life itself’—that is to say, the strongest life seeks to ascend, which necessarily places it above weaker life. This is a simple, common sense observation—some people are healthier, stronger, braver, smarter, more beautiful than others, and they reap the rewards for it. This is anti-Christian in the sense that it is worldly—differences and details of this life matter, and these differences will necessarily lead to uneven outcomes in the hierarchy.

At the top of the social pyramid, there are delicious fruits called privileges. But there is a certain privilege in being mediocre; life is more difficult the higher up you go because of the tremendous responsibility, competition and pressure. Employment—crafts, trade, farming, science, most of art—depends on people with mediocre abilities and desires:

To be a public utility, a wheel, a function – you need to be destined for this by nature: it is not society but rather the type of happiness that the vast majority of people cannot rise above that make them intelligent machines. For the mediocre, mediocrity is a happiness; mastery of one thing, specialization as a natural instinct. It would be completely unworthy of a more profound spirit to have any objection to mediocrity as such.

Mediocrity is needed before there can be exceptions: it is the condition for a high culture. When an exceptional person treats a mediocre one more delicately than he treats himself and his equals, this is not just courtesy of the heart,— it is his duty . . .

Nietzsche sort of agrees but also diverges with Aristotle; natural slaves are destined for mediocrity, but this is their happiness—the golden pyramid has more gold the farther down you go. Some empirical data supports Nietzsche’s view; scholars like Ed and Carol Diener published a study in the late 1990s called Most People Are Happy, where they looked at nationally representative surveys and found that out of 43 nations, 86% of them had what was termed a ‘positive level of subjective well-being’, or SWB.

My skepticism is inflamed when I read stuff like this, because a survey is quite low as a scientific standard, and serious-sounding designations like SWB mask the lack of hard science. Yet it matches my life experience—when I go into the city and see people enjoying themselves, my overwhelming impression is that wageslaves can, in fact, be very happy indeed—most of them, at least. Brunch on the patio, colourful night clubs, cappuccinos, lattes, cosmopolitans, fun festivals, exciting concerts, blockbuster movies, steak and lobster dinners, world-class sports teams, quick hookups—bread and circus abounds.

In other words, it’s the sulking minority who struggles to understand the happy majority; here’s an excerpt of a post I found on the Incels.is forum: ‘At every job I’ve worked they have always kept me at the bottom of the barrel and talked down to me as if I am an idiot because I do not share their delusional sad state of “muh positive vibes bro”. A little bit of extra salt in that dish!

That number mentioned earlier—86%—is a rough approximation of a complex, subjective phenomenon but it’s an interesting figure because it’s almost the inverted image of anti-depressant use—about 18% of women and 8% of guys pop happy pills in the US. I think those drugs are dangerous and wildly over-prescribed, but that makes an even better case for the observation by team Diener; that most people like being alive most of the time. And drugs like sugar, weed, coffee, booze, and opiates all help fill the gap—psychedelics help people heal their minds and find extravagant joy in the most mundane things.

There is no shortage of fun and cheap consolations, but also profound luxuries—some hidden; Foster points out that in the Renaissance, the poet Beccadelli sold one of his country estates to buy a copy of Livy’s History of Rome—a book now freely and easily accessible online, although many wouldn’t take it for free. And yet, amidst these pleasures, there are those who wish to stir up trouble:

Who do I hate most among the rabble today? The socialist rabble, the Chandala-apostles who undermine workers’ instincts and pleasures, their feelings of modesty about their little existences, — who make them jealous, who teach them revenge . . . Injustice is never a matter of unequal rights, it is a matter of claiming ‘equal’ rights . . . What is bad? But I have already said it: everything that comes from weakness, from jealousy, from revenge. — The anarchist and the Christian are descended from the same lineage.

Again, Nietzsche’s observation echoes my experience—I’ve noticed a thirst for power and revenge masking itself with noble robes. Recall what Frederick Douglass said—there’s a great temptation among everybody to grab the whip and make subordinates. ‘Tax the rich‘ and ‘eat the rich‘ have become common phrases, further spreading resentment and hollowing out trust between employees and employers. This makes me think of a song from the ’60s by Malvina Reynolds called Little Boxes, it’s sung in a annoying voice as a way to make fun of her target—boring suburbs—little boxes made of ticky tacky and they all look just the same. I hate suburban conformity too, but I’m imagining an anthropologist going to a remote village with huts and making fun of them for being homogenous and boring—sounds to me like a cranky old person attacking a bunch of strangers—I’m imagining grandpa Simpsons shaking his fist at the clouds. My translation of her sarcastic message is ‘hey, lookat me, I live in the suburbs and I’m boring and dumb and lame‘. Reynolds wrote it while going to the Friends Committee on Legislation—a nonprofit that promotes peace and justice—and it might just be my ears but I’m not getting a lot of inclusive love vibes from the song, more like vengeful contempt for society. Compare it with Vashti Bunyan’s Just Another Diamond Day, a gentle song resting in a deep love and admiration for existence that sees a grain of wheat like a glowing gem, that sings of giving love and food to children—something that she actually spent most of her life doing. Maybe Reynolds inspired people to reach for something greater than mediocre life in the suburbs, to help their creativity flourish, and that’s great—but who would you rather have on the peace committee?

But! Just because someone is wealthy and upper-class doesn’t mean they automatically have a grand spirit—they might be focused on making money, showing off, and buying up property out of boredom rather than contributing to the flourishing of higher culture. How many people at the top treat the mediocre more delicately than they treat themselves and their equals? What great spirits can we find? What comes to my mind is King Philip II and El Escorial, a palace about an hour’s drive north-west of Madrid. It’s a strange name for a palace; escoria means slag-heap, scum—in Cuba, escoria is used to describe losers—escorial is a dump—as you can see, this is quite the opposite; a fun little piece of humility, I suppose. Although unlike some people who sing about how much they hate boring people and buildings, Philip endeavored to actually create fantastic beauty that transcends time.

I think he succeeded—after all, UNESCO declared it a World Heritage Site, and over half a million people visit it every year—over 1000 people a day—so I’d call it a homerun. For our purposes it’s worth mentioning because King Philip II was hundreds of years ahead of the curve, not just because he instated an early form of the assembly line, but because he treated his workers very well. In distinction to everybody else, Philip issued a Royal Edict that specified the work-day; four hours in the morning and four in the afternoon, organized in a way that’s convenient for the workers and lets them take care of their personal health. They had ten days of vacation, a full salary, and half-pay during any recovery from illness or injury. Could be better, but it’s pretty good, and it didn’t require thousands of people rioting in the streets—he just had the kind of spirit that understood it’s his duty to treat people that way for society to function properly.

It took 35 years to build—what 35-year marvel of beauty are we dedicated to now—what is beauty to a fragmented culture? How can we cultivate the kind of spirit that has strength, valor and vision—while possessing a magnanimous attitude towards its inferiors? We can certainly see failed attempts and small spirits in recent history. Nicolae Ceausescu—the Romanian dictator who was in power when I was born—ordered the construction of the world’s largest administrative building, Casa Poporului—the House of The People!—slightly larger in volume than the Great Pyramid of Giza, a monstrosity was built with forced labour, soldiers, and a lot ‘volunteers’ to cut costs—all the while, citizens were starving and babies were dying in the hospital from a lack of electricity in the winter. While Philip believed in something more than himself, Ceausescu was mostly concerned with the glory of Ceausescu—a petty spirit. No doubt influenced by his painful and harsh life; he ran away from home as a young kid and spent a lot of time locked up in prison for his political agitation—ironically, in the name of worker’s rights.

6. The Worker’s Future

I think one of the frustrations of being employed is that an employee is—almost by definition—discouraged from being creative; delegating tasks means that orders must be followed, so personal autonomy is sacrificed. This sacrifice seems to be a necessary feature of the fact that people are not equal, and some are suited to being above others—but this is a painful sacrifice that can drive many to suicidal despair. It’s not easy to sacrifice your autonomy, your creativity, the most vital part of your soul just because you have been bested by someone more powerful. We need more great spirits that reach out with delicacy to the average worker.

In The Greek State, Nietzsche expresses what he thought was the brazen ancient Greek instinct: to the victor belongs the vanquished, with wife and child, life and property. Power gives the first right, and there is no right, which at bottom is not presumption, usurpation, violence. But remember the words of Queen Clytemnestra uttered after murdering King Agamemnon in an act of vengeance :

As he sinned by the sword,

So is death by the sword his atonement

That is to say, if you want to play power politics—watch your back!

You’re entering a dangerous space filled with predators—where buoyant ideals drown in blood. Jordan Peterson makes the case that power isn’t necessarily just a blind, brutal thing—it can be oriented towards the power of competence, benevolence, and creativity—it can design El Escorial and be generous towards workers.

Part of a project of building a high culture might involve a loving eye towards mediocrity—to recognize the sacrifices that people make on a regular basis to keep the social organism intact, one that blooms rare and precious flowers. Not to stir up destructive storms of vengeance but soft rains that foster growth and abundance. Easier said than done.

I think that’s why people like Peterson make such a big deal out of Christianity; King Philip II was a devout Catholic, and his pro-social behaviour might have been related to his faith. In any case, modern Christianity is more akin to the Roman Empire’s values rather than the original repudiation of it—it stands for respecting authority, tradition, ritual, family, convention, responsibility—not a bad idea if you want a stable and reliable place to live. I don’t hear a lot of people citing St. Paul and explaining that total celibacy and retreat into a monastery is their ideal—my impression of people that describe themselves as Christian is: — they come from a moderately successful, conservative family; they care about education, raising kids, hard work, practical success, and polite manners. Boring, yes, but they’re not going to be throwing molotov cocktails at my grandma’s building.

People like David Mitchell joke about how it’s a good thing that people working crappy jobs are nasty to everybody, because they should be upset at having their brains rot. Resentment is understandable and relatable—I’m filled with it myself, I wouldn’t have obsessively thought about this topic otherwise—but the question is, what is its direction? What will it build after it tears down its target? The common parental wisdom here is that being a resentful loser is poison for everybody; so clean your room, organize your resources, plan for your ambitions, strengthen the relationships with your family and friends, prove your worth to the world—and maybe, just maybe, your life will get better. But—keep in mind that suffering is guaranteed, so you need to find your meaning or else you’ll collapse—and meaning comes from being part of a group. Durkheim pointed out that a way to reduce egoistic suicide—the kind of suicide that comes about from being alienated from society—is to join a group. Any group. Christianity is strongly influenced by the idea of accepting the outcasts, and it encourages pro-social group behaviour which is are essential for a healthy culture. At the very least, it’s fun to sing with strangers and connect with the community on a regular basis. Religion might be a soothing substance for the masses, but why should we masses avoid having our pain soothed? Why not enjoy the necessary relief of a good TV show, an afternoon lunch with a friend, a dance party with a family, a stoned cuddle session with a lover? There’s no doubt that hedonism can be taken to a destructive extreme—dramatized in Nietzsche’s concept of the Last Man—but it might play an important role in redirecting resentment to something more beneficial.

I see people posting Peterson’s own messy room, effectively saying—’see, you’re not perfect! you slipped up!’. But Peterson has had thousands of people earnestly declare that his advice has dramatically improved their lives—I find he often gives good pep talks to snap me out of a resentful state of mind, to focus on healthier goals. What are his detractors doing to improve the lot of directionless, angry young people—people who are waiting for an excuse to take revenge against God, or Society, or The Universe? Will they write songs about he’s a stupid alt-right Neo-Nazi grifter and his audience is a bunch of pathetic incels? Well—good luck with that. Once, I got a call from an old lady who was in tears, giving me effusive compliments because of my drawing of Madonna and Christ, which I had sold to her grandson, and it was a lovely feeling. Highly recommended.

So, going back to the painting by Domenico di Tommaso Curradi di Boffo Bigordi—a.k.a. Domenico Ghirlandaio—I’ll put this broad but important question to you:

Come farai a essere il nipote del tuo vecchio?

Che tipo di vecchio sarai per tuo nipote?

King Philip II might add: ¿Cuál es tu Escorial?