What do you call a group that isn’t a group?

A contradiction? A trick? A joke?

Al-Ghurabā’—The Strangers—exists as a name, but nothing more. No membership, no shared ideology, no consensus.

Its root—غ ر ب (Ghain Reh Beh)—carries the weight of distance, remoteness, estrangement. Ghurabā’ (غرباء) is the plural; for a single Stranger, it’s Gharīboon (غريب).

The line above the ‘a‘, followed by the apostrophe, means you flatten out the last letter and round it off with an ‘ooh‘ sound. So it’ll sound like ghoora-bah-ooh. Luckily the transliteration can only approximate the sounds, so it retains its distance.

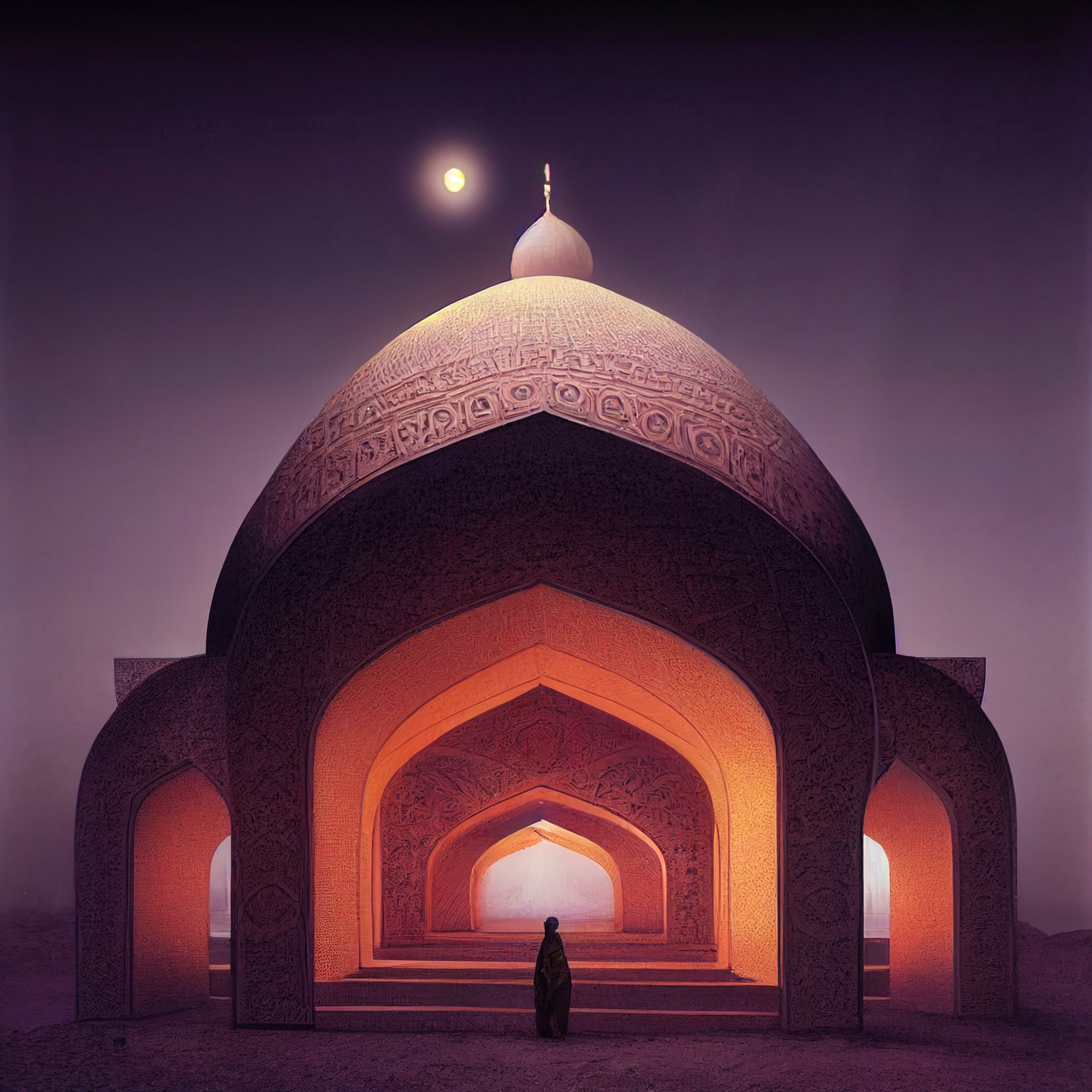

Here’s what the flag looks like—it simply says stranger in Arabic script:

But of course, this is a lie—this flag is false. The first and only tenet of Al-Ghurabā is that they share a name but no content. No gharib can speak for another gharib, and one cannot assume a gharib’s beliefs based on their status as a gharib.

There is no official nor unofficial membership. A Gharīboon actively denies their membership. In fact, any and all Gharīboon should actively discourage membership, and denounce all members. It’s a term which actively seeks to frustrate semiotic depth so as to retain its distance. To always be—strange.

Al-Ghurabā’ is a placeholder, a cipher, a refusal. A whisper of recognition between strangers in a crowded room. Nothing more. And yet, that nothing is everything.

So, dear Stranger, keep your distance, but stay close.

And if you obey most of those in the earth, they will lead you astray from Allah’s way; they follow but conjecture and they only lie.

Quran 6:116